Eerie Presents: 'El Cid'

While it’s certainly true that Marvel’s Stan Lee was ever ready to publish imitations of James Warren’s line of black and white comic magazines, it’s also true that Warren, and Eerie editor Bill DuBay, were only happy to return the favor by cashing in on the success of some of Marvel’s properties, most notably ‘Conan the Barbarian’, which by the mid-70s was a resounding financial success, particularly when presented in the higher-priced, non-Comics Code regulated Curtis Publication magazines, like ‘Savage Sword of Conan’.

One of the Conan imitations / inspirations that appeared in Eerie was El Cid, written by Budd Lewis and illustrated by the Mexican artist Gonzalo Mayo. El Cid appeared in Eerie #65 (April 1975), #66 (June 1975), #70 (November 1975), and #71 (January 1976).

Now Dark Horse’s New Comics Company imprint provides all the El Cid stories in the latest of its hardbound ‘Eerie Presents’ volumes.

Like the proceeding volumes in the New Comics Company series (‘Eerie Presents: Hunter’, ‘Creepy: Berni Wrightson’, and ‘Creepy: Richard Corben’), this allows admirers of the old Warren books to get high-quality, but very affordable, reproductions of selected stories / creators, without having to invest substantial sums of money to purchase each $49.99 volume in the dedicated Creepy and Eerie hardcover 'Archives' volumes.

With El Cid, writer Lewis took a real-life historical personage from 11th century Spain, and placed him as a sword-and-sorcery hero in a heroic fantasy landscape akin to that afforded Conan or King Kull.

Mayo’s art had the florid style common to the Spanish and Filipino artists working for Warren in the 70s, and is very well reproduced here.

In his Introduction to this volume, Dark Horse / New Comics editor Dan Braun relates an amusing anecdote: several years ago (before DuBay's death from colon cancer in April, 2010), he and an unidentified companion went to visit with former Warren magazines editor Bill DuBay in Portland, Oregon, as part of their ongoing 'Eerie Presents' projects

(Braun leaves unsaid the implication that financial transactions of some sort, relating to the Warren properties, were going to be discussed at the meeting....a topic that brought some degree of contention between DuBay and the New Comics Company reps).

Arriving at the meeting place, Braun discovered that Budd Lewis had joined DuBay.

At the start of the meeting, Braun's companion uttered a laudatory remark about James Warren, a remark which elicited an immediate, obscenity-laced, fit of rage from Budd Lewis - !

"Buddy, any friend of Warren ain't no friend of mine !"

Lewis's rage may have been a side-effect of his unfortunate financial circumstances (at least, as of 2011), which saw him and his wife trying to earn a living operating a hot dog cart, while battling illness and the lack of a permanent home. Hopefully Budd's life has changed for the better as March, 2013 arrives.

Fans of worthy graphic art, and Warren’s output during the 70s, will want a copy of ‘Eerie Presents: El Cid’. Needless to say, although the cover price is $15.99, discounted copies are readily available at your obvious online retailer.

SO....what's a PorPor Book ? 'PorPor' is a derogatory term my brother used, to refer to the SF and Fantasy paperbacks and comic books I eagerly read from the late 60s to the late 80s. This blog is devoted to those paperbacks and comics you can find on the shelves of second-hand bookstores...from the New Wave era and 'Dangerous Visions', to the advent of the cyberpunks and 'Neuromancer'. And with a leavening of pop culture detritus, too !

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Thursday, March 28, 2013

'1984' issue 2

Warren magazines, August, 1978

After observing the success of National Lampoon's Heavy Metal magazine, James Warren decided to have his own 'adult' sf magazine out on the stands.

Titled 1984, the magazine premiered in June, 1978. In 1980 it was retitled 1994 after legal action from author George Orwell's estate, and went on to issue 29 (February 1983) before ceasing publication when Warren went bankrupt.

Considering that editor Bill Dubay was also handling Warren's other publications (James Warren was too miserly to hire the necessary additional editorial staff), 1984 wasn't a bad magazine, but it never achieved the success of Heavy Metal, or its imitator from Marvel, Epic Illustrated.

Dubay's sought to lure a male, 15 - 25 year-old readership by supplying 1984 with sf comics based on the salacious themes used in the humor strips then appearing in Penthouse and Hustler.

Indeed, 1984 was to be sold only to those over 18 years of age, although I suspect few store proprietors in those halcyon days of the late 70s would've turned away would-be purchasers.

Modern readers, accustomed to the access to universal porn provided by the internet, will no doubt find the content of 1984 rather tame, even insipid in its silliness.

Here's 'Scourge of the Spaceway', with story by Dubay and artwork by Esteban Maroto. The script has the smarmy, locker-room humor of many of 1984's stories.

Warren magazines, August, 1978

After observing the success of National Lampoon's Heavy Metal magazine, James Warren decided to have his own 'adult' sf magazine out on the stands.

Titled 1984, the magazine premiered in June, 1978. In 1980 it was retitled 1994 after legal action from author George Orwell's estate, and went on to issue 29 (February 1983) before ceasing publication when Warren went bankrupt.

Considering that editor Bill Dubay was also handling Warren's other publications (James Warren was too miserly to hire the necessary additional editorial staff), 1984 wasn't a bad magazine, but it never achieved the success of Heavy Metal, or its imitator from Marvel, Epic Illustrated.

Dubay's sought to lure a male, 15 - 25 year-old readership by supplying 1984 with sf comics based on the salacious themes used in the humor strips then appearing in Penthouse and Hustler.

Indeed, 1984 was to be sold only to those over 18 years of age, although I suspect few store proprietors in those halcyon days of the late 70s would've turned away would-be purchasers.

Modern readers, accustomed to the access to universal porn provided by the internet, will no doubt find the content of 1984 rather tame, even insipid in its silliness.

Here's 'Scourge of the Spaceway', with story by Dubay and artwork by Esteban Maroto. The script has the smarmy, locker-room humor of many of 1984's stories.

Monday, March 25, 2013

Book Review: The Catalyst

Book Review: 'The Catalyst' by Charles L. Harness

3 / 5 Stars

‘The Catalyst’ (191 pp.) was published by Pocket Books in February 1980. The cover illustration is by Michael Whelan.

While the cover gives the impression that ‘Catalyst’ is a touchy-feely novel with strong mystical overtones, at heart, it’s a tale about a chemical company and its struggle to patent a method for synthesis of a new ‘wonder molecule’.

It’s 2006, and at the Ashkettles Chemical Corporation on Long Island, patent attorney Paul Blandford finds himself increasingly drawn into the work of the corporation’s Research Lab, where the charismatic organic chemist John Serane and his team are hard at work on an optimal synthesis for the compound ‘trialine’.

Knowledge that a competitor in Germany is also busily at work on an improved synthesis method lends an urgency to the Ashkettles team’s efforts.

Unfortunately for Blandford, Serane, and the research team, Ashkettles’ management has insisted on making the ultimate corporate sycophant their new Director of Research.

Not only does Fred Kussman make the 'Pointy-Haired Boss' in the 'Dilbert' strips look like a paradigm of enlightened leadership, but his actions threaten the progress of the synthesis team.

Paul Blandford discovers that, despite being an attorney and not a scientist, his participation is key to any hope of success for the Research Lab…..and he’ll get help from a most unexpected source……

The central narrative of ‘Catalyst’, dealing with an insider’s view of how chemical companies convert their science achievements into patents and ultimately, commercial formulations, is an engaging and a worthwhile read.

However, author Harness also tries to infuse his novel with a sub-plot involving the spiritual manifestations of Blandford’s since-departed older brother, Billy.

Indeed, some of the same metaphysical elements Harness employs in other of his fiction works make their appearances in ‘Catalyst’. These attempts to infuse the book with a determinedly humanistic element, to balance the mercenary machinations of the corporate culture, seem an uneasy fit at times.

‘Catalyst’ is worth picking up, having as its subject matter a topic – organic chemistry - that rarely gets much coverage in the sf literature. However, you must be willing to tolerate the supernatural angle that periodically intrudes on the narrative.

‘The Catalyst’ (191 pp.) was published by Pocket Books in February 1980. The cover illustration is by Michael Whelan.

While the cover gives the impression that ‘Catalyst’ is a touchy-feely novel with strong mystical overtones, at heart, it’s a tale about a chemical company and its struggle to patent a method for synthesis of a new ‘wonder molecule’.

It’s 2006, and at the Ashkettles Chemical Corporation on Long Island, patent attorney Paul Blandford finds himself increasingly drawn into the work of the corporation’s Research Lab, where the charismatic organic chemist John Serane and his team are hard at work on an optimal synthesis for the compound ‘trialine’.

Knowledge that a competitor in Germany is also busily at work on an improved synthesis method lends an urgency to the Ashkettles team’s efforts.

Unfortunately for Blandford, Serane, and the research team, Ashkettles’ management has insisted on making the ultimate corporate sycophant their new Director of Research.

Not only does Fred Kussman make the 'Pointy-Haired Boss' in the 'Dilbert' strips look like a paradigm of enlightened leadership, but his actions threaten the progress of the synthesis team.

Paul Blandford discovers that, despite being an attorney and not a scientist, his participation is key to any hope of success for the Research Lab…..and he’ll get help from a most unexpected source……

The central narrative of ‘Catalyst’, dealing with an insider’s view of how chemical companies convert their science achievements into patents and ultimately, commercial formulations, is an engaging and a worthwhile read.

However, author Harness also tries to infuse his novel with a sub-plot involving the spiritual manifestations of Blandford’s since-departed older brother, Billy.

Indeed, some of the same metaphysical elements Harness employs in other of his fiction works make their appearances in ‘Catalyst’. These attempts to infuse the book with a determinedly humanistic element, to balance the mercenary machinations of the corporate culture, seem an uneasy fit at times.

‘Catalyst’ is worth picking up, having as its subject matter a topic – organic chemistry - that rarely gets much coverage in the sf literature. However, you must be willing to tolerate the supernatural angle that periodically intrudes on the narrative.

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Monday, March 18, 2013

Book Review: Omnivore

Book Review: 'Omnivore' by Piers Anthony

1 / 5 Stars

Since he published his first short story in 1963, and his first novel (‘Cthon’) in 1967, Piers Anthony (the pen name of English sf author Piers Anthony Jacob) has published nearly 150 books.

Obviously, some of this massive output is going to be mediocre, even awful, while some will be highly readable and engaging.

Unfortunately, ‘Omnivore’ falls into the ‘mediocre’ category.

Omnivore was first published in 1968; this Avon paperback (221 pp) was released in October, 1978, with a fine cover illustration by Ron Walotsky.

Succeeding volumes in the ‘Of Man and Manta’ trilogy include ‘Orn’ (1970), and ‘Ox’ (1976).

The plot of Omnivore is simple and straightforward: a federal agent named Subble, possessed of superhuman physical and mental attributes, is dispatched to interview / investigate three people who have recently returned from exploring the planet Nacre.

These three individuals are Veg, a burly, extroverted vegetarian; Cal, a sickly scientific genius who can barely walk unassisted in normal-grav worlds; and Aquilon, a stunning blonde whose beauty masks an inner psychological turmoil.

With each interview, Subble learns more about what the trio experienced on the world of Nacre, where it seems that all of the larger, sentient animals – herbivore, omnivore, and carnivore – are descended from fungi.

It turns out that the trio have smuggled juvenile Nacrean carnivores – creatures referred to as ‘mantas’ – back to Earth. Having underestimated the intelligence and physical fortitude of the mantas, the trio have unwittingly exposed their home planet to an alien life form that could change the destiny of all life on Earth….and it’s up to Subble to figure out how to avert disaster……

By the standards of late 60s sf, Omnivore is no worse, and no better, in terms of plotting than other works of the time. But the prose is poorly executed.

The author is intent on making his novel ‘deep’ and loaded with profound insights into the nature of life, evolution, and destiny – in short, Anthony intended that Omnivore, while superficially an sf novel (a genre often assumed in the late 60s to be juvenile and amateurish in nature), transcends the boundaries of simple genre fiction, to stand as a work of literature.

The truth is, Anthony couldn’t pull it off; at the time he wrote Omnivore, his skills as a writer weren’t sufficiently developed to produce the novel he intended.

As a result, the reader must prepare for lengthy conversations taking place among the protagonists, conversations filled with empty phrases and stilted dialogue.

He or she also must prepare for sections of text in which the narrative gets placed on hold, while the author expounds on such topics as the role of fungi in Earth’s ecology; nemativorous fungi (?!); fungi and hallucinogens (there is a bizarre LSD ‘trip’ sequence in the novel); and industrial food animal production (?!).

As I waded through ‘Omnivore’ trying to digest these pedantic episodes, the overall momentum of the narrative gradually wilted away, until by the time the denouement shuffled into view, I simply wanted to end it all..... and get my review written up.

Needless to say, I’m not looking forward to tackling ‘Orn’ and ‘Ox’.

But, mindful that Anthony could produce some worthy sf –and here the ‘Battle Circle’ trilogy comes readily to mind – maybe I’ll forge ahead.

Maybe.

1 / 5 Stars

Since he published his first short story in 1963, and his first novel (‘Cthon’) in 1967, Piers Anthony (the pen name of English sf author Piers Anthony Jacob) has published nearly 150 books.

Obviously, some of this massive output is going to be mediocre, even awful, while some will be highly readable and engaging.

Unfortunately, ‘Omnivore’ falls into the ‘mediocre’ category.

Omnivore was first published in 1968; this Avon paperback (221 pp) was released in October, 1978, with a fine cover illustration by Ron Walotsky.

Succeeding volumes in the ‘Of Man and Manta’ trilogy include ‘Orn’ (1970), and ‘Ox’ (1976).

The plot of Omnivore is simple and straightforward: a federal agent named Subble, possessed of superhuman physical and mental attributes, is dispatched to interview / investigate three people who have recently returned from exploring the planet Nacre.

These three individuals are Veg, a burly, extroverted vegetarian; Cal, a sickly scientific genius who can barely walk unassisted in normal-grav worlds; and Aquilon, a stunning blonde whose beauty masks an inner psychological turmoil.

With each interview, Subble learns more about what the trio experienced on the world of Nacre, where it seems that all of the larger, sentient animals – herbivore, omnivore, and carnivore – are descended from fungi.

It turns out that the trio have smuggled juvenile Nacrean carnivores – creatures referred to as ‘mantas’ – back to Earth. Having underestimated the intelligence and physical fortitude of the mantas, the trio have unwittingly exposed their home planet to an alien life form that could change the destiny of all life on Earth….and it’s up to Subble to figure out how to avert disaster……

By the standards of late 60s sf, Omnivore is no worse, and no better, in terms of plotting than other works of the time. But the prose is poorly executed.

The author is intent on making his novel ‘deep’ and loaded with profound insights into the nature of life, evolution, and destiny – in short, Anthony intended that Omnivore, while superficially an sf novel (a genre often assumed in the late 60s to be juvenile and amateurish in nature), transcends the boundaries of simple genre fiction, to stand as a work of literature.

The truth is, Anthony couldn’t pull it off; at the time he wrote Omnivore, his skills as a writer weren’t sufficiently developed to produce the novel he intended.

As a result, the reader must prepare for lengthy conversations taking place among the protagonists, conversations filled with empty phrases and stilted dialogue.

He or she also must prepare for sections of text in which the narrative gets placed on hold, while the author expounds on such topics as the role of fungi in Earth’s ecology; nemativorous fungi (?!); fungi and hallucinogens (there is a bizarre LSD ‘trip’ sequence in the novel); and industrial food animal production (?!).

As I waded through ‘Omnivore’ trying to digest these pedantic episodes, the overall momentum of the narrative gradually wilted away, until by the time the denouement shuffled into view, I simply wanted to end it all..... and get my review written up.

Needless to say, I’m not looking forward to tackling ‘Orn’ and ‘Ox’.

But, mindful that Anthony could produce some worthy sf –and here the ‘Battle Circle’ trilogy comes readily to mind – maybe I’ll forge ahead.

Maybe.

Friday, March 15, 2013

Heavy Metal March 1983

'Heavy Metal' magazine, March 1983

March, 1983...... the single 'The Safety Dance', by Canadian group Men Without Hats, is released in the US, after having some degree of chart success in Canada at the end of 1982. The accompanying video , shot in the English village of West Kington, soon is in heavy rotation on MTV.

The latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is on the stands, with a wraparound cover by Carol Donner. The advertising gets a bit quirky, with a full-page ad from Gold Eagle Books, the publisher of 'mack Bolan' and other adventure novels. Undoubtedly, Gold Eagle was hoping to tap into the young white male market served by Heavy Metal.

One of the best features of this month's issue is a lengthy interview with underground comix legend S. Clay Wilson, responsible for such beloved characters as the Checkered Demon, Ruby the Dyke, and Star-Eyed Stella. Sadly, Wilson remains disabled and in poor health from a brain injury suffered in November, 2008.

From the interview: "The Angels were fighting in one room, while (Janis) Joplin was singing to the hippies in the other. It was like one of my drawings come to life."

Brilliant !

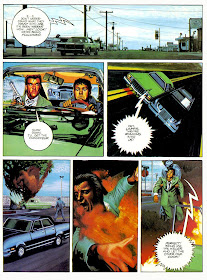

Among the better comic strips appearing in the March issue is the violent, satirical 'Lamar: Killer of Fools' by P. Setbon and P. Poirier.

March, 1983...... the single 'The Safety Dance', by Canadian group Men Without Hats, is released in the US, after having some degree of chart success in Canada at the end of 1982. The accompanying video , shot in the English village of West Kington, soon is in heavy rotation on MTV.

The latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is on the stands, with a wraparound cover by Carol Donner. The advertising gets a bit quirky, with a full-page ad from Gold Eagle Books, the publisher of 'mack Bolan' and other adventure novels. Undoubtedly, Gold Eagle was hoping to tap into the young white male market served by Heavy Metal.

The Dossier section leads off with Rok Critic Lou Stathis turning his attention to...comic books !? Fear not, Stathis's commentary is as pretentious and self-serving as for his Rock reviews. Indeed, the entire Dossier section for this issue is devoted to comics.

Also chipping in their two cents' worth are comics creators and luminaries Walt Simonson, Byron Preiss, Will Eisner, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Kurtzman.

One of the best features of this month's issue is a lengthy interview with underground comix legend S. Clay Wilson, responsible for such beloved characters as the Checkered Demon, Ruby the Dyke, and Star-Eyed Stella. Sadly, Wilson remains disabled and in poor health from a brain injury suffered in November, 2008.

From the interview: "The Angels were fighting in one room, while (Janis) Joplin was singing to the hippies in the other. It was like one of my drawings come to life."

Brilliant !

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

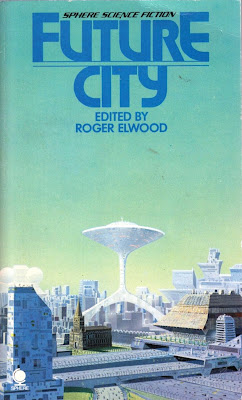

Book Review: Future City

Book Review: 'Future City' edited by Roger Elwood

4 / 5 Stars

‘Future City’ was originally published in 1973; in the US, a paperback edition was published in June, 1974, by Pocket Books, with a cover illustration by Michael Gross. The UK paperback edition (236 pp) was released in 1976 by Sphere Books, with a luminous cover illustration by Angus McKie.

Roger Elwood gained some degree of notoriety as a dedicated assembler and editor of large numbers of shoddy anthologies in the 70s, clearing a path for the late Martin Greenberg to launch his own career as Mega-Editor of more than 1200 anthologies.

But ‘Future City’ is reasonably good, particularly as an example of the Eco-catastrophe and Population Bomb themes prevalent in early 70s sf.

Clifford Simak and Frederik Pohl provide the Foreward and Afterward essays, respectively.

There are a few poems included in ‘Future City’: ‘In Praise of New York’ by Thomas Disch, ‘As A Drop’ by D. M. Price, and ‘Abendlandes’ by Virginia Kidd. None of them are particularly noteworthy.

My capsule summaries of the short-story contents:

‘The Sightseer’ by Ben Bova: short-short story of modern suburbanites visiting a domed New York City for illicit thrills. Bova expanded this story into his 1976 novel ‘City of Darkness’, which in turn was the spiritual precursor to the entire ‘Escape From New York’ genre of sf.

‘Meanwhile, We Eliminate’ by Andrew J. Offutt: Offutt uses capital letters in his surname in association with this tale, a sure sign that he was not employing Speculative Fiction Pretentiousness. A good story about Future City traffic run amok.

‘Thine Alabaster Cities Gleam’ by Laurence M. Janifer: an office tower’s HVAC system develops problems.

‘Culture Lock’ by Barry M. Malzburg: A rare, coherently plotted entry from Malzburg, who usually was besotted with the figurative prose of the New Wave movement. A very effective story of a Future City in which homosexual behavior – and participation in gay orgies (!) – is mandatory. Disturbing at the time of its publication, and still disturbing today.

‘The World As Will and Wallpaper’ by R. A. Lafferty: contrived entry, featuring prose designed to mimic that of the Speculative Fiction movement’s major inspiration, Thomas Pynchon. A young man searches Future City for clues to the Meaning of Life.

‘Violation’ by William F. Nolan: moving violations on Future City’s streets.

‘City Lights, City Nights’ by K. M. O’Donnell: underwhelming tale of an arrogant young director whose low-budget film production recruits city residents.

‘The Undercity’ by Dean R. Koontz: clever tale of Wiseguys operating in Future City.

‘Apartment Hunting’ by Harvey and Audrey Bilker: nicely written tale in which a couple make a harried application for living space in the overpopulated Future City.

‘The Weariest River’ by Thomas N. Scortia: immortality loses its appeal when you live in a dystopian Future City. Not the most accessible story, but one with a gritty, proto-Cyberpunk sensibility to it.

‘Death of A City’ by Frank Herbert: two city planners have a metaphysical debate. The worst entry in the anthology.

‘Assassins of Air’ by George Zebrowski: Horatio Alger meets a polluted metropolis.

‘Getting Across’ by Robert Silverberg: reasonably entertaining novelette about a man confronting the breakdown of his section of the global mega-city. As always with Silverberg’s fiction of this period, essentially a story about Relationships, rather than a hardcore sf tale per se.

‘In Dark Places’ by Joe L. Hensley: gritty, grim tale of racial warfare in a decrepit Future City. Another of the best stories in the anthology, also exhibiting an offbeat, proto-Cyberpunk sensibility.

‘Revolution’ by Robin Schaeffer: a confusing allegory about robots and their human charges.

‘Chicago’ by Thomas F. Monteleone: the future metropolis is completely automated; a robot questions why.

‘The Most Primitive’ by Ray Russell: short-short tale, cleverly assembled.

‘Hindsight: 480 Seconds’ by Harlan Ellison: obligatory entry from Ellison. The last days of future city, with added pathos. Pedestrian.

‘5,000,000 AD’ by Miriam Allen deFord: mordant tale of man’s last days.

In summary, 'Future City' is one of the better Elwood anthologies, and a good snapshot of where the genre stood in in 1973 in terms of depicting future dystopias. Worth searching out.

4 / 5 Stars

‘Future City’ was originally published in 1973; in the US, a paperback edition was published in June, 1974, by Pocket Books, with a cover illustration by Michael Gross. The UK paperback edition (236 pp) was released in 1976 by Sphere Books, with a luminous cover illustration by Angus McKie.

Roger Elwood gained some degree of notoriety as a dedicated assembler and editor of large numbers of shoddy anthologies in the 70s, clearing a path for the late Martin Greenberg to launch his own career as Mega-Editor of more than 1200 anthologies.

But ‘Future City’ is reasonably good, particularly as an example of the Eco-catastrophe and Population Bomb themes prevalent in early 70s sf.

Clifford Simak and Frederik Pohl provide the Foreward and Afterward essays, respectively.

There are a few poems included in ‘Future City’: ‘In Praise of New York’ by Thomas Disch, ‘As A Drop’ by D. M. Price, and ‘Abendlandes’ by Virginia Kidd. None of them are particularly noteworthy.

My capsule summaries of the short-story contents:

‘The Sightseer’ by Ben Bova: short-short story of modern suburbanites visiting a domed New York City for illicit thrills. Bova expanded this story into his 1976 novel ‘City of Darkness’, which in turn was the spiritual precursor to the entire ‘Escape From New York’ genre of sf.

‘Meanwhile, We Eliminate’ by Andrew J. Offutt: Offutt uses capital letters in his surname in association with this tale, a sure sign that he was not employing Speculative Fiction Pretentiousness. A good story about Future City traffic run amok.

‘Thine Alabaster Cities Gleam’ by Laurence M. Janifer: an office tower’s HVAC system develops problems.

‘Culture Lock’ by Barry M. Malzburg: A rare, coherently plotted entry from Malzburg, who usually was besotted with the figurative prose of the New Wave movement. A very effective story of a Future City in which homosexual behavior – and participation in gay orgies (!) – is mandatory. Disturbing at the time of its publication, and still disturbing today.

‘The World As Will and Wallpaper’ by R. A. Lafferty: contrived entry, featuring prose designed to mimic that of the Speculative Fiction movement’s major inspiration, Thomas Pynchon. A young man searches Future City for clues to the Meaning of Life.

‘Violation’ by William F. Nolan: moving violations on Future City’s streets.

‘City Lights, City Nights’ by K. M. O’Donnell: underwhelming tale of an arrogant young director whose low-budget film production recruits city residents.

‘The Undercity’ by Dean R. Koontz: clever tale of Wiseguys operating in Future City.

‘Apartment Hunting’ by Harvey and Audrey Bilker: nicely written tale in which a couple make a harried application for living space in the overpopulated Future City.

‘The Weariest River’ by Thomas N. Scortia: immortality loses its appeal when you live in a dystopian Future City. Not the most accessible story, but one with a gritty, proto-Cyberpunk sensibility to it.

‘Death of A City’ by Frank Herbert: two city planners have a metaphysical debate. The worst entry in the anthology.

‘Assassins of Air’ by George Zebrowski: Horatio Alger meets a polluted metropolis.

‘Getting Across’ by Robert Silverberg: reasonably entertaining novelette about a man confronting the breakdown of his section of the global mega-city. As always with Silverberg’s fiction of this period, essentially a story about Relationships, rather than a hardcore sf tale per se.

‘In Dark Places’ by Joe L. Hensley: gritty, grim tale of racial warfare in a decrepit Future City. Another of the best stories in the anthology, also exhibiting an offbeat, proto-Cyberpunk sensibility.

‘Revolution’ by Robin Schaeffer: a confusing allegory about robots and their human charges.

‘Chicago’ by Thomas F. Monteleone: the future metropolis is completely automated; a robot questions why.

‘The Most Primitive’ by Ray Russell: short-short tale, cleverly assembled.

‘Hindsight: 480 Seconds’ by Harlan Ellison: obligatory entry from Ellison. The last days of future city, with added pathos. Pedestrian.

‘5,000,000 AD’ by Miriam Allen deFord: mordant tale of man’s last days.

In summary, 'Future City' is one of the better Elwood anthologies, and a good snapshot of where the genre stood in in 1973 in terms of depicting future dystopias. Worth searching out.