'Jim' by Luc Cornillon

from the November, 1979 issue of Heavy Metal magazine

Satiric humor infuses this strip, about an enthusiastic young man on his first safari to an unknown land....except he is maybe a little too enthusiastic.....

SO....what's a PorPor Book ? 'PorPor' is a derogatory term my brother used, to refer to the SF and Fantasy paperbacks and comic books I eagerly read from the late 60s to the late 80s. This blog is devoted to those paperbacks and comics you can find on the shelves of second-hand bookstores...from the New Wave era and 'Dangerous Visions', to the advent of the cyberpunks and 'Neuromancer'. And with a leavening of pop culture detritus, too !

Friday, November 29, 2013

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Book Review: The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn

Book Review: 'The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn' by Algis Budrys

0 / 5 Stars

‘The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn’ (159 pp) was published by Fawcett’s Gold Medal imprint in 1967; the cover artwork is by Frank Frazetta.

As the novel opens, its protagonist, White Jackson, is striding across the desert of the un-named planet on which he and the descendants of the original Terran colonists survive (amid greatly reduced circumstances). Jackson is on his Manhood Quest, which involves setting off into the desert in order to pursue and kill an indigenous, bird-like alien humanoid: an Amsir.

In the course of his Quest, Jackson is startled to discover that much of what he has been told of the Amsirs, and life in the bedraggled confines of the human colony, are lies and fictions, designed to maintain a precarious social order.

Perhaps the remainder of the novel has something to do with Jackson’s path to discovering the truth about his heritage, the Amsirs, and the fate of the colony. But after I reached page 40, I gave up and tossed ‘The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn’ away.

This is one of the worst sf books I’ve ever attempted to read.

Algis Budrys was plainly going through the motions with this piece. The novel shows every sign of being hastily assembled and subjected to little, if any, editing. The prose is stilted and often afflicted with such poor syntax that entire paragraphs are simply empty verbiage:

It came to him that he’d spent a lot of years running around the Thorn and pitching darts to come to the moment he realized it was all downhill from here on. But it was all downhill. And when he thought of all the people he’d seen follow that road, and the way they did it because they’d all heard the elders telling them and telling them how to do it, White Jackson realized that the track to Ariwol was beaten many times as hard as the track around the Thorn.

Far from being an undiscovered gem of late 60s sf, ‘ The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn’ is best left to deserved obscurity.

0 / 5 Stars

‘The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn’ (159 pp) was published by Fawcett’s Gold Medal imprint in 1967; the cover artwork is by Frank Frazetta.

As the novel opens, its protagonist, White Jackson, is striding across the desert of the un-named planet on which he and the descendants of the original Terran colonists survive (amid greatly reduced circumstances). Jackson is on his Manhood Quest, which involves setting off into the desert in order to pursue and kill an indigenous, bird-like alien humanoid: an Amsir.

In the course of his Quest, Jackson is startled to discover that much of what he has been told of the Amsirs, and life in the bedraggled confines of the human colony, are lies and fictions, designed to maintain a precarious social order.

Perhaps the remainder of the novel has something to do with Jackson’s path to discovering the truth about his heritage, the Amsirs, and the fate of the colony. But after I reached page 40, I gave up and tossed ‘The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn’ away.

This is one of the worst sf books I’ve ever attempted to read.

Algis Budrys was plainly going through the motions with this piece. The novel shows every sign of being hastily assembled and subjected to little, if any, editing. The prose is stilted and often afflicted with such poor syntax that entire paragraphs are simply empty verbiage:

It came to him that he’d spent a lot of years running around the Thorn and pitching darts to come to the moment he realized it was all downhill from here on. But it was all downhill. And when he thought of all the people he’d seen follow that road, and the way they did it because they’d all heard the elders telling them and telling them how to do it, White Jackson realized that the track to Ariwol was beaten many times as hard as the track around the Thorn.

Far from being an undiscovered gem of late 60s sf, ‘ The Amsirs and the Iron Thorn’ is best left to deserved obscurity.

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Heavy Metal November 1983

'Heavy Metal' magazine November 1983

November, 1983, and on MTV, in heavy rotation, is 'Say Say Say' by Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson.

The November issue of Heavy Metal magazine is out, with a front cover by Dave Dorman, and a back cover by De Es Schwertberger.

The contents of this month's issue are unremarkable. There are more installments of 'Odyssey', 'The Fourth Song', 'Tex Arcana', and 'Ranxerox'.

There is an interview with Will Eisner, who also provides a brief strip of 'The Spirit'. I consider Eisner's 'Spirit' to be one of the most over-rated comics of the 20th century, and the appearance of the character in this issue of HM does nothing to persuade me otherwise.

Crepax provides a new 'Valentina' comic, but his whole '60s fashion meets fetish' approach was outdated and unoriginal even back in 1983.

Reading this issue, the one thing that stands out is the absence of the artists that made the magazine great in its first several years of life.

No Suydam, no Caza, no Nicollet........no Jeronaton, no Macedo, no Schuiten Brothers, no Druillet......

A halfway decent singleton comic is 'As In A Dream' by Miltos Scouras, which I've posted below.

November, 1983, and on MTV, in heavy rotation, is 'Say Say Say' by Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson.

The November issue of Heavy Metal magazine is out, with a front cover by Dave Dorman, and a back cover by De Es Schwertberger.

The contents of this month's issue are unremarkable. There are more installments of 'Odyssey', 'The Fourth Song', 'Tex Arcana', and 'Ranxerox'.

There is an interview with Will Eisner, who also provides a brief strip of 'The Spirit'. I consider Eisner's 'Spirit' to be one of the most over-rated comics of the 20th century, and the appearance of the character in this issue of HM does nothing to persuade me otherwise.

Crepax provides a new 'Valentina' comic, but his whole '60s fashion meets fetish' approach was outdated and unoriginal even back in 1983.

Reading this issue, the one thing that stands out is the absence of the artists that made the magazine great in its first several years of life.

No Suydam, no Caza, no Nicollet........no Jeronaton, no Macedo, no Schuiten Brothers, no Druillet......

A halfway decent singleton comic is 'As In A Dream' by Miltos Scouras, which I've posted below.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Book Review: The Dying Earth

Book Review: 'The Dying Earth' by Jack Vance

4 / 5 Stars

This paperback edition of ‘The Dying Earth’ (which was originally published in 1950) was released by Lancer Books in 1962, and features cover artwork by Ed Emshwiller.

This is the first volume in what is now known as the ‘Dying Earth’ tetralogy, the other volumes being ‘The Eyes of the Overworld’ (1966), ‘Cugel’s Saga’ (1983), and ‘Rhialto the Marvellous’ (1984).

‘The Dying Earth’ is comprised of eight loosely connected stories, all set in the fantasy landscape of a far-future Earth, in which the Sun is a sullen red ball, bereft of energy. Millennia have passed since the 20th century, and much of Man’s achievements long have been buried by the passage of time. There are still sizeable cities scattered around the globe, but the lands between are either wasteland or wilderness, inhabited by various monsters and bands of troglodytes. Whatever technology still exists is that scrabbled from the remnants of long-dead empires.

The cities are by no means entirely safe, for wizards are plentiful ,and operate outside the boundaries of what little law remains. Throughout the ‘Dying Earth’ novels, much of the action revolves around the efforts of various protagonists to free themselves from some obligation or debt made to a cunning, often pitiless wizard.

Most of the stories in ‘Dying’ range in mood and theme. The first three tales, ‘Turjan of Miir’, and continuing with ‘Mazirian the Magician’, and ‘T’Sais’, center on action and adventure, as their protagonists seek to overcome the machinations of evil magicians.

‘Liane the Wayfarer’ is an effective horror story. ‘Ulan Dhor’ and ‘Guyal of Sfere’ tend more towards a fantasy / sci-fi tenor, as these characters venture into the ruins of former civilizations possessed of wondrous technologies.

For stories first written in 1950, the entries in ‘The Dying Earth’ have a very modern prose styling, and are markedly superior to the sf of their time, which was still centered on a pulp approach to characterization and plotting. This being Vance, of course, readers will need to have Google handy to look up obscure adjectives and adverbs. However, the writing adeptly mixes descriptive passages with a concise, fast-moving sense of plotting and pace, something lacking to a large extent in modern fantasy literature.

Copies of ‘The Dying Earth’ in good condition can be expensive; I recommend obtaining the omnibus edition, ‘Tales of the Dying Earth’ (2000), available from Orb Books; this trade paperback is affordable.

4 / 5 Stars

This paperback edition of ‘The Dying Earth’ (which was originally published in 1950) was released by Lancer Books in 1962, and features cover artwork by Ed Emshwiller.

This is the first volume in what is now known as the ‘Dying Earth’ tetralogy, the other volumes being ‘The Eyes of the Overworld’ (1966), ‘Cugel’s Saga’ (1983), and ‘Rhialto the Marvellous’ (1984).

‘The Dying Earth’ is comprised of eight loosely connected stories, all set in the fantasy landscape of a far-future Earth, in which the Sun is a sullen red ball, bereft of energy. Millennia have passed since the 20th century, and much of Man’s achievements long have been buried by the passage of time. There are still sizeable cities scattered around the globe, but the lands between are either wasteland or wilderness, inhabited by various monsters and bands of troglodytes. Whatever technology still exists is that scrabbled from the remnants of long-dead empires.

The cities are by no means entirely safe, for wizards are plentiful ,and operate outside the boundaries of what little law remains. Throughout the ‘Dying Earth’ novels, much of the action revolves around the efforts of various protagonists to free themselves from some obligation or debt made to a cunning, often pitiless wizard.

Most of the stories in ‘Dying’ range in mood and theme. The first three tales, ‘Turjan of Miir’, and continuing with ‘Mazirian the Magician’, and ‘T’Sais’, center on action and adventure, as their protagonists seek to overcome the machinations of evil magicians.

‘Liane the Wayfarer’ is an effective horror story. ‘Ulan Dhor’ and ‘Guyal of Sfere’ tend more towards a fantasy / sci-fi tenor, as these characters venture into the ruins of former civilizations possessed of wondrous technologies.

For stories first written in 1950, the entries in ‘The Dying Earth’ have a very modern prose styling, and are markedly superior to the sf of their time, which was still centered on a pulp approach to characterization and plotting. This being Vance, of course, readers will need to have Google handy to look up obscure adjectives and adverbs. However, the writing adeptly mixes descriptive passages with a concise, fast-moving sense of plotting and pace, something lacking to a large extent in modern fantasy literature.

Copies of ‘The Dying Earth’ in good condition can be expensive; I recommend obtaining the omnibus edition, ‘Tales of the Dying Earth’ (2000), available from Orb Books; this trade paperback is affordable.

Monday, November 18, 2013

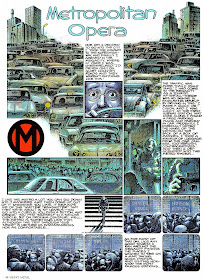

Metropolitan Opera by Caza

'Metropolitan Opera' by Caza

from the November, 1980 issue of Heavy Metal magazine

Another imaginative examination of urban frustration, from the pen of Caza....

from the November, 1980 issue of Heavy Metal magazine

Another imaginative examination of urban frustration, from the pen of Caza....

Saturday, November 16, 2013

Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky

Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky

'Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky' (112 pp.) was published by UK's Paper Tiger 2000.

Ron Waltosky was a prolific illustrator of sf and fantasy paperbacks throughout the 70s and 80s. This volume provides a good overview of his works during that interval.

During the 70s, when Avon Books (USA) published many of Piers Anthony's works, Walotsky was the cover artist, and those readers seeing the illustrations for 'Kirlian Quest' amd other works will get a shot of Instant Nostalgia.

Needless to say, Walotsky's colorful, imaginative artwork often was featured on the covers of books by other authors.

Walotsky also provided artwork for the horror genre, as in this cover for Stephen King's 'Carrie':

In addition to covers for paperbacks, Walotsky also handled commissions for posters and studio art pieces:

The 1990s saw him providing cover art for sf magazines:

One of the more impressive cover paintings Walotsky did was for this 1988 sf novel:

As well as one of the more memorable covers ('Tightrope') for Heavy Metal magazine (the October, 1978 issue).

'Inner Visions', like all the Paper Tiger art books, is printed on quality paper stock and the printing of the reproductions is very good. Fans of sf and fantasy artwork will want to have a copy.

'Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky' (112 pp.) was published by UK's Paper Tiger 2000.

Ron Waltosky was a prolific illustrator of sf and fantasy paperbacks throughout the 70s and 80s. This volume provides a good overview of his works during that interval.

During the 70s, when Avon Books (USA) published many of Piers Anthony's works, Walotsky was the cover artist, and those readers seeing the illustrations for 'Kirlian Quest' amd other works will get a shot of Instant Nostalgia.

Needless to say, Walotsky's colorful, imaginative artwork often was featured on the covers of books by other authors.

Walotsky also provided artwork for the horror genre, as in this cover for Stephen King's 'Carrie':

In addition to covers for paperbacks, Walotsky also handled commissions for posters and studio art pieces:

'Spaceman', poster for the Third Eye Company, 1971

The 1990s saw him providing cover art for sf magazines:

One of the more impressive cover paintings Walotsky did was for this 1988 sf novel:

Cover painting for 'Destiny's End' by Tim Sullivan, Avon Books, 1988

As well as one of the more memorable covers ('Tightrope') for Heavy Metal magazine (the October, 1978 issue).

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Blood on Black Satin episode two

'Blood on Black Satin' episode two

by Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy

Episode Two (from Eerie #110, April 1980)

by Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy

Episode Two (from Eerie #110, April 1980)

Monday, November 11, 2013

Book Review: The Machine in Shaft Ten

Book Review: 'The Machine in Shaft Ten' by M. John Harrison

‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’ (174 pp) was published in the UK in 1975 by Panther Books, and features cover artwork by Chris Foss. The stories it compiles were first published in the late 60s and early 70s in New Worlds and other sf magazines.

‘Machine’ is an eclectic collection that represents some of the worst, and some of the best, New Wave sf.

Of the twelve stories in ‘Machine’, four - The Bait Principle, The Orgasm Band, Visions of Monad, and The Bringer with the Window – are all ‘experimental’ fictions in which a series of loosely-connected vignettes are presented to the reader, charging him or her with fashioning their own narrative from the presented material. This sort of short story was prevalent in the New Wave era, and has aged badly.

The remaining stories in ‘Machine’ are, however, among the best Harrison has written and display the imagination and creativity that the New Wave movement brought to sf.

All of these, to one degree or another, are preoccupied with entropy, and while it’s true that the New Wave movement as a whole certainly was preoccupied with entropy, Harrison was one of the few authors who didn’t simply try to emulate J. G. Ballard, but instead injected his own interpretation of the idea into his fiction.

The stories in ‘Machine’ present entropy in striking visual terms: it’s always November; there are fields of corroded metal spars, abandoned buildings with walls encrusted with mold, fogs and mists concealing great heaps of disintegrating machinery, alienated characters seeking shelter in bombed-out ruins created by a war since forgotten, etc.

Poking through these entropic visions are sharp, nasty acts of violence and cruelty.

The lead story, ‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’, deals with the discovery of a possible alien artifact churning away deep within the earth’s core. This discovery spawns a new religious cult with ambivalent implications for the fate of humankind.

‘The Lamia and Lord Chromis’ is a Viriconium story, and today, more than 40 years later, still one of the most offbeat and imaginative fantasy stories ever written. The plot is not particularly original, but the atmosphere and themes, which borrow somewhat from Jack Vance, brought a new sensibility to the genre.

‘Running Down’, about a man afflicted with entropy, was also very creative for its time, and while overly long, and tending to belabor rock climbing (Harrison’s favorite past-time), it too remains relevant as an example of sf that extends the genre.

‘Events Witnessed from a City’ is another Viriconium tale, and while it adopts the episodic nature of the ‘experimental’ pieces, it's more coherent, and delivers a uniquely downbeat ending.

In ‘London Melancholy’, a race of winged humans cautiously explore a London destroyed by a war with a race of unusual aliens. Fusing entropy with the sf trope of alien invaders, it’s one of the better New Wave stories ever written.

‘Ring of Pain’ also is set in the fog-wreathed ruins of an English city, but here, it’s a personal sort of violence visited on the survivors who crawl through the dripping ruins.

‘The Causeway’ takes place on an unnamed planet where the narrator endeavors to discover the origins and purpose of a mysterious, enormous bridge that stretches for what may be hundreds of miles across the sea. Downbeat, melancholy, and with a twist ending.

‘Coming from Behind’ is another alien invasion tale. A deserter named Prefontaine makes his way through a bleak landscape of abandoned buildings and deserted roadways, hiding from his pursuers. He discovers that his moral obligations may outweigh his interests in self-preservation.

In summary, ‘Machine’ is well worth getting, even though almost half its contents are New Wave affectations that haven’t endured well. The remaining ‘traditional’ stories more than make up for the less-impressive entries.

4 / 5 Stars

‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’ (174 pp) was published in the UK in 1975 by Panther Books, and features cover artwork by Chris Foss. The stories it compiles were first published in the late 60s and early 70s in New Worlds and other sf magazines.

‘Machine’ is an eclectic collection that represents some of the worst, and some of the best, New Wave sf.

Of the twelve stories in ‘Machine’, four - The Bait Principle, The Orgasm Band, Visions of Monad, and The Bringer with the Window – are all ‘experimental’ fictions in which a series of loosely-connected vignettes are presented to the reader, charging him or her with fashioning their own narrative from the presented material. This sort of short story was prevalent in the New Wave era, and has aged badly.

The remaining stories in ‘Machine’ are, however, among the best Harrison has written and display the imagination and creativity that the New Wave movement brought to sf.

All of these, to one degree or another, are preoccupied with entropy, and while it’s true that the New Wave movement as a whole certainly was preoccupied with entropy, Harrison was one of the few authors who didn’t simply try to emulate J. G. Ballard, but instead injected his own interpretation of the idea into his fiction.

The stories in ‘Machine’ present entropy in striking visual terms: it’s always November; there are fields of corroded metal spars, abandoned buildings with walls encrusted with mold, fogs and mists concealing great heaps of disintegrating machinery, alienated characters seeking shelter in bombed-out ruins created by a war since forgotten, etc.

Poking through these entropic visions are sharp, nasty acts of violence and cruelty.

The lead story, ‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’, deals with the discovery of a possible alien artifact churning away deep within the earth’s core. This discovery spawns a new religious cult with ambivalent implications for the fate of humankind.

‘The Lamia and Lord Chromis’ is a Viriconium story, and today, more than 40 years later, still one of the most offbeat and imaginative fantasy stories ever written. The plot is not particularly original, but the atmosphere and themes, which borrow somewhat from Jack Vance, brought a new sensibility to the genre.

‘Running Down’, about a man afflicted with entropy, was also very creative for its time, and while overly long, and tending to belabor rock climbing (Harrison’s favorite past-time), it too remains relevant as an example of sf that extends the genre.

‘Events Witnessed from a City’ is another Viriconium tale, and while it adopts the episodic nature of the ‘experimental’ pieces, it's more coherent, and delivers a uniquely downbeat ending.

In ‘London Melancholy’, a race of winged humans cautiously explore a London destroyed by a war with a race of unusual aliens. Fusing entropy with the sf trope of alien invaders, it’s one of the better New Wave stories ever written.

‘Ring of Pain’ also is set in the fog-wreathed ruins of an English city, but here, it’s a personal sort of violence visited on the survivors who crawl through the dripping ruins.

‘The Causeway’ takes place on an unnamed planet where the narrator endeavors to discover the origins and purpose of a mysterious, enormous bridge that stretches for what may be hundreds of miles across the sea. Downbeat, melancholy, and with a twist ending.

‘Coming from Behind’ is another alien invasion tale. A deserter named Prefontaine makes his way through a bleak landscape of abandoned buildings and deserted roadways, hiding from his pursuers. He discovers that his moral obligations may outweigh his interests in self-preservation.

In summary, ‘Machine’ is well worth getting, even though almost half its contents are New Wave affectations that haven’t endured well. The remaining ‘traditional’ stories more than make up for the less-impressive entries.