Book Review: 'The Madness Season' by C. S. Friedman

1 / 5 Stars

‘The Madness Season’ (495 pp) was published by DAW Books in October, 1990. The cover painting is by Michael Whelan.

I got to page 236 of the book’s 495 total pages before boredom overcame me, and I abandoned ‘The Madness Season’.

‘Season’ certainly has an interesting premise: for three hundred years, Earth has been in subjugation to the Tyr, a race of reptilian aliens who communicate telepathically and adhere to a caste-based social structure.

The Tyr ensure Earth’s continued vassalage by rapidly identifying anyone who could be a potential rebel or troublemaker, and either summarily executing them, or exiling them to colony planets in deep space.

Daetrin, the hero of the story, is a vampire, with vamparism here defined as a metabolic disorder that requires the acquisition of vital nutrients from human or animal blood. The mutation has the benefit of bestowing immortality, superhuman strength, and superhuman sensory awareness to those who carry it.

Since the advent of the Tyr victory over Earth, Daetrin has entered into a kind of waking sleep, deliberately forgetting his past, forgoing ambition, and shielding any and all hopes for the future, with the goal of cloaking his true nature from the Tyr.

As the novel opens, however, Daetrin is discovered and sentenced by the Tyr to exile on a colony planet. Once aboard the Tyrran starship, deprived of nutrients, under surveillance, and aware that any misstep on his part will result in death, Daetrin struggles to survive. For despite his exile, he has one overwhelming goal: discover the Tyrran’s carefully-hidden weakness, and use it to defeat their empire……

‘Season’ starts off promisingly with its 'one-vampire-against-the Evil-Empire' motif, but unfortunately, once Daetrin finds himself aboard the Tyrran starship, author C[elia] S. Friedman diverts from the major plot thread in order to use overwrought, heavily descriptive text to belabor the psychological and emotional traumas through which Daetrin will come to terms with his true nature.

As these psychodramas – usually manifested in the form of lengthy internal monologues, and flashbacks using a different font to signal to the reader how profound and important they are to Understanding Our Character – accumulate in length, the main narrative – how to overthrow the aliens ? – recedes into the background.

It doesn’t help matters when the author starts to insert several subplots into the storyline; one of these, involving a female representative of a shape-shifting alien race called the Marra, is designed to lend a note of romance to the narrative. But these subplots really do nothing more than pad the novel.....and at 495 pp., ‘Season’ is simply too long, and could have benefited from being edited down to half its length.

I can’t recommend ‘The Madness Season’ to anyone except those who yearn for a character-driven story that puts forth the well-worn trope that defeating the aliens requires that our heroes first come to terms with Understanding Their Humanity before the fight can be taken to the enemy.

SO....what's a PorPor Book ? 'PorPor' is a derogatory term my brother used, to refer to the SF and Fantasy paperbacks and comic books I eagerly read from the late 60s to the late 80s. This blog is devoted to those paperbacks and comics you can find on the shelves of second-hand bookstores...from the New Wave era and 'Dangerous Visions', to the advent of the cyberpunks and 'Neuromancer'. And with a leavening of pop culture detritus, too !

Monday, June 30, 2014

Saturday, June 28, 2014

Thursday, June 26, 2014

Book Review: Image of the Beast and Blown

Book Review: 'Image of the Beast' and 'Blown' by Philip Jose Farmer

3 / 5 Stars

In 1968, Philip Jose Farmer contracted with Essex House, a California-based publisher of pornographic novels, to write three books: Image of the Beast (1968); its sequel, Blown (1969); and a satire / homage to Doc Savage and Tarzan, titled A Feast Unknown (1969). This decision drew much attention and admiration in sci-fi circles, because while traditionally many sf authors (Robert Silverberg most notably) had written for the porno fiction market, this usually was done using pseudonyms.

Essex House titles were distributed by ‘Parliament News, Inc.’, the company set up by 1960s smut tycoon Milton Luros to supply magazines and sleaze novels to retailers. Too highbrow for the traditional porn readership of the era, and unable to gain shelf space in reputable bookstores, Essex failed to earn much market share, and it closed up shop in 1969.

3 / 5 Stars

In 1968, Philip Jose Farmer contracted with Essex House, a California-based publisher of pornographic novels, to write three books: Image of the Beast (1968); its sequel, Blown (1969); and a satire / homage to Doc Savage and Tarzan, titled A Feast Unknown (1969). This decision drew much attention and admiration in sci-fi circles, because while traditionally many sf authors (Robert Silverberg most notably) had written for the porno fiction market, this usually was done using pseudonyms.

Farmer’s decision to write under his own name instantly bestowed

upon him the maverick, ‘rebel’ aura that engendered considerable envy from

other writers jostling for the cutting-edge, avant-garde hipster status that so

defined coolness in sf’s New Wave Era. Indeed, a number of other sf authors

wrote for Essex House, including Samuel R. Delaney.

Essex House titles were distributed by ‘Parliament News, Inc.’, the company set up by 1960s smut tycoon Milton Luros to supply magazines and sleaze novels to retailers. Too highbrow for the traditional porn readership of the era, and unable to gain shelf space in reputable bookstores, Essex failed to earn much market share, and it closed up shop in 1969.

Playboy Press issued this omnibus edition (336 pp.) of Image of the Beast and Blown in October, 1979; the cover illustration is by Enric.

The book does not demarcate between the two novels, with Blown appearing unannounced, as chapter 21 (out of 45 total); however, because Blown is a sequel to Image, this is only a minor drawback to the two novels’ continuity.

Image is set in Los Angeles, ca. the late 1960s. The city is in the grip of an eco-disaster, due to the advent of a massive smog storm that has triggered a mass exodus from the city. Anyone hoping to negotiate the greenish pall of smog must wear a gas mask, and drive with their headlights on, even in mid-day.

As Image opens the hero, private eye Herald Childe, joins his former LAPD squadmates in the department’s film room, there to view a ‘snuff’ film sent to the police. The film purportedly has something to do with the recent disappearance of Matthew Colben, Childe’s partner in their detective agency.

As Childe and the police watch, the film pans to show a nude, drugged Colben strapped to a table in an unidentified room. An exotic-looking women is avidly performing certain erotic activities on the panting and gasping Colben.

As the film proceeds, the woman steps away from the table and carefully inserts a pair of false teeth into her mouth. Teeth that are shiny and sharp, and made from metal. Then she turns once again to the bound and helpless Colben…..

As the police and Childe recover from witnessing an atrocity on film, they struggle to understand why Colben has been kidnapped and singled out as a victim. Determined to find out who mutilated and murdered his partner, Herald Childe finds himself obliged to consort with a crew of Southern California eccentrics, including a mysterious European ‘Count’ living in a gated mansion in Beverly Hills.

As Childe pursues his investigation, he becomes entangled with a cult devoted to perversion, depravity, and death….and not all of its members are truly human…….

Are Image and Blown for everyone ? Not really, particularly if you're not inclined towards splatterpunk. I found the books entertaining, although not as fun as A Feast Unknown. Hence, a 3 of 5 Stars rating.

The book does not demarcate between the two novels, with Blown appearing unannounced, as chapter 21 (out of 45 total); however, because Blown is a sequel to Image, this is only a minor drawback to the two novels’ continuity.

Image is set in Los Angeles, ca. the late 1960s. The city is in the grip of an eco-disaster, due to the advent of a massive smog storm that has triggered a mass exodus from the city. Anyone hoping to negotiate the greenish pall of smog must wear a gas mask, and drive with their headlights on, even in mid-day.

As Image opens the hero, private eye Herald Childe, joins his former LAPD squadmates in the department’s film room, there to view a ‘snuff’ film sent to the police. The film purportedly has something to do with the recent disappearance of Matthew Colben, Childe’s partner in their detective agency.

As Childe and the police watch, the film pans to show a nude, drugged Colben strapped to a table in an unidentified room. An exotic-looking women is avidly performing certain erotic activities on the panting and gasping Colben.

As the film proceeds, the woman steps away from the table and carefully inserts a pair of false teeth into her mouth. Teeth that are shiny and sharp, and made from metal. Then she turns once again to the bound and helpless Colben…..

As the police and Childe recover from witnessing an atrocity on film, they struggle to understand why Colben has been kidnapped and singled out as a victim. Determined to find out who mutilated and murdered his partner, Herald Childe finds himself obliged to consort with a crew of Southern California eccentrics, including a mysterious European ‘Count’ living in a gated mansion in Beverly Hills.

As Childe pursues his investigation, he becomes entangled with a cult devoted to perversion, depravity, and death….and not all of its members are truly human…….

As with A Feast Unknown, which I reviewed here, Image and Blown are written with a tongue-in-cheek style (probably not what the

Essex House editorial staff were necessarily expecting) that pays homage to

Farmer’s habit of working all manner of sci-fi tropes and personalities into

his narrative.

For example, in Blown a major supporting character is none

other than Forrest J Ackerman (pictured above), the ‘Forry’ of Famous Monsters of Filmland. Farmer depicts him as a fussy neurotic who falls asleep after staying up late

to edit the latest issue of Vampirella.

The scenes of sex and violence that appear in both novels

are written with a deadpan, even droll attitude which makes these two novels

more of sci-fi 'insider' comedies than genuine porn. The novels’ comedic aspects

are reinforced by Farmer’s decision to include some plot developments that are

so over-the-top and so contrived (I won’t disclose any spoilers, but I will say

that the snakelike creature clinging to the leg of the woman depicted on Blown's covers lives in a Very Special Place) that it’s quite clear he was

treating these two Essex House assignments as an exercise in facetiousness.

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Frank Miller's Ronin

Frank Miller's Ronin

By 1983, Frank Miller's work on Daredevil had garnered him sufficient praise and standing in the comics industry for him to be able to do a so-called creator-owned property for DC.

'Frank Miller's Ronin' was issued as a six-issue series, starting in July, 1983, and appearing more or less bimonthly until August, 1984. This 1987 graphic novel compiles all six issues (unfortunately, however, the covers of the individual comics are not reproduced) and features an introduction by Jeff Rovin.

The setting: New York City ca. 2030, a wasteland inhabited by ultraviolent street gangs and under-city cannibals straight out of Escape from New York.

Despite the city's horrible condition, the Aquarius corporation has nonetheless erected an enormous facility in the midst of this wasteland; within the facility, 'biocircuitry' has been engineered to create a sentient computer entity known as Virgo.

An armless and legless young man named Billy Challas serves as the main programmer / controller for Virgo, by virtue of his telekinetic abilities.

As the novel opens, in medieval Japan, the nameless ronin of the book's title is engaged in a death match with a demon named Agat; the ronin seeks vengeance, for Agat had killed his master.

Agat contrives to teleport both himself, and the ronin, to the far future - the New York City of Aquarius corporation. There, Agat uses his shapeshifting ability to take over the identity of Taggert, the corporate director for Aquarius.

The ronin finds himself alone and weaponless in the streets of the city; through some metamorphosis, part of Billy Challas's personality has merged with his own.

As 'Frank MIller's Ronin' unfolds, the ronin embarks on a hazardous, often violent journey through the unlikely hell of modern New York City, his goal: to find and kill Agat. The demon, for his part, unleashes the Aquarius security chief - a woman named Casey McKenna - to hunt down an eliminate the ronin.

But as the ronin leaves a trail of death and mayhem among the city's underworld, McKenna comes to question her mission, and the changes being made to the Aquarius corporation by a suddenly mercenary and amoral Taggert. Soon McKenna will have to make a choice: ally with the ronin, or her employer......

'Frank MIller's Ronin' mixes and matches a healthy quantity of early 80s sci-fi and pop culture tropes and themes. As I already mentioned, its vision of New York City is influenced by Escape from New York. There also are prominent elements of what at that time was the brand-new genre of cyberpunk. As well, the early 80s interest in all things Japanese finds an outlet in the character of the ronin himself.

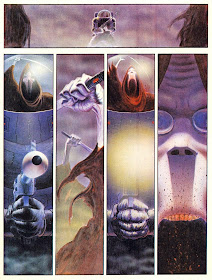

In my opinion, 'Ronin' has not aged well. Much of this is due to the fact that Miller simply isn't a very accomplished draftsman. As with his other comics, 'Ronin' relies on a wide range of visual contrivances to direct attention from this fact......the use of unconventional panel configurations, unusual coloring schemes, multiple points of view within the same sequence of panels, as well as the elimination of all but a few sound effects. Other comic book staples - swoosh marks, external narration, thought balloons- are jettisoned.

In the absence of such staples, reading 'Ronin' can be tedious at times, particularly when Miller's artwork is so figurative that one cannot make out what, exactly, is going on. Too many times, in the absence of well-delinated artwork and external narration, the plot momentarily lapses into incoherence.

Modern readers are going to find Ronin's coloring scheme rather weak; the color printing of mainstream comic books of the early 80s simply isn't very good compared to what is now achievable with computer-aided composition and coloring.

'Frank Miller's Ronin' may be worth searching out if you are someone dedicated to comics of the early 80s, or are simply curious about Miller's initial forays into the medium, forays that since have led to his highly influential position in the comic book world of today. Anyone else will probably want to pass on this compilation.

By 1983, Frank Miller's work on Daredevil had garnered him sufficient praise and standing in the comics industry for him to be able to do a so-called creator-owned property for DC.

'Frank Miller's Ronin' was issued as a six-issue series, starting in July, 1983, and appearing more or less bimonthly until August, 1984. This 1987 graphic novel compiles all six issues (unfortunately, however, the covers of the individual comics are not reproduced) and features an introduction by Jeff Rovin.

The setting: New York City ca. 2030, a wasteland inhabited by ultraviolent street gangs and under-city cannibals straight out of Escape from New York.

Despite the city's horrible condition, the Aquarius corporation has nonetheless erected an enormous facility in the midst of this wasteland; within the facility, 'biocircuitry' has been engineered to create a sentient computer entity known as Virgo.

An armless and legless young man named Billy Challas serves as the main programmer / controller for Virgo, by virtue of his telekinetic abilities.

As the novel opens, in medieval Japan, the nameless ronin of the book's title is engaged in a death match with a demon named Agat; the ronin seeks vengeance, for Agat had killed his master.

Agat contrives to teleport both himself, and the ronin, to the far future - the New York City of Aquarius corporation. There, Agat uses his shapeshifting ability to take over the identity of Taggert, the corporate director for Aquarius.

The ronin finds himself alone and weaponless in the streets of the city; through some metamorphosis, part of Billy Challas's personality has merged with his own.

As 'Frank MIller's Ronin' unfolds, the ronin embarks on a hazardous, often violent journey through the unlikely hell of modern New York City, his goal: to find and kill Agat. The demon, for his part, unleashes the Aquarius security chief - a woman named Casey McKenna - to hunt down an eliminate the ronin.

But as the ronin leaves a trail of death and mayhem among the city's underworld, McKenna comes to question her mission, and the changes being made to the Aquarius corporation by a suddenly mercenary and amoral Taggert. Soon McKenna will have to make a choice: ally with the ronin, or her employer......

'Frank MIller's Ronin' mixes and matches a healthy quantity of early 80s sci-fi and pop culture tropes and themes. As I already mentioned, its vision of New York City is influenced by Escape from New York. There also are prominent elements of what at that time was the brand-new genre of cyberpunk. As well, the early 80s interest in all things Japanese finds an outlet in the character of the ronin himself.

In my opinion, 'Ronin' has not aged well. Much of this is due to the fact that Miller simply isn't a very accomplished draftsman. As with his other comics, 'Ronin' relies on a wide range of visual contrivances to direct attention from this fact......the use of unconventional panel configurations, unusual coloring schemes, multiple points of view within the same sequence of panels, as well as the elimination of all but a few sound effects. Other comic book staples - swoosh marks, external narration, thought balloons- are jettisoned.

In the absence of such staples, reading 'Ronin' can be tedious at times, particularly when Miller's artwork is so figurative that one cannot make out what, exactly, is going on. Too many times, in the absence of well-delinated artwork and external narration, the plot momentarily lapses into incoherence.

Modern readers are going to find Ronin's coloring scheme rather weak; the color printing of mainstream comic books of the early 80s simply isn't very good compared to what is now achievable with computer-aided composition and coloring.

'Frank Miller's Ronin' may be worth searching out if you are someone dedicated to comics of the early 80s, or are simply curious about Miller's initial forays into the medium, forays that since have led to his highly influential position in the comic book world of today. Anyone else will probably want to pass on this compilation.

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

'Heavy Metal' magazine June 1984

'Heavy Metal' magazine June 1984

June, 1984, and in heavy rotation on MTV is Billy Idol's 'Eyes Without a Face.'

The latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is out, featuring a front cover by Esteban Maroto and a back cover by James Cherry.

There is a great Contents Page illustration by Herikberto, titled 'Butterfly' :

Some good material in this issue, including more of Frank Thorne's cheesecake series 'Lann', Renard and Schuiten's 'The Railways', 'Salammbo II' by Druillet, and 'A Matter of Time' by Gimenez. I'll be posting some of this stuff later this month.

For now, here is the concluding installment of Charles Burns's 'El Borbah: Living in the Ice Age'.

Monday, June 16, 2014

Book Review: Bring the Jubilee

Book Review: 'Bring the Jubilee' by Ward Moore

1 / 5 Stars

'Bring the Jubilee’ first was published in 1953; this Avon SF paperback version (222 pp.) was published in May, 1972. The cover artist is uncredited.

The novel opens with an intriguing statement: Hodge Blackmaker, the first-person narrator, is writing this - his memoir - in 1877. However, he was born in 1921. How did Hodge Blackmaker come to be writing his memoir decades before he even was born ?

The opening chapters disclose the circumstances of Blackmaker’s birth and upraising: born the only child of a dour couple of modest means, living in the town of Wappingers Falls, New York. In this ‘alternity’ of the US, the Union was defeated at Gettysburg, and the Confederacy triumphed in the Civil War.

The twenty-six states of the federal government are economically and culturally backward, akin to the plight of the Southern states in the post-Civil War era of ‘our’ timeline. European powers exploit the states of the Northeast, a state of affairs endorsed by the South, which, even as it prospers, has little interest in improving the lot of the defeated Yankees. For the overwhelming majority of US citizens, a joyless lifetime of indentured servitude is the best they can hope to attain.

With aspirations to find a calling more rewarding than scrabbling for a living from farming, the teenaged Hodge leaves home for New York City, where he finds employment, and greater awareness of the depressing state of a world made real by the defeat of the Union.

As the narrative progresses, Blackmaker is introduced to the underworld of Union resistance in a New York City where it's the early 1940s, and the Second World War has never happened. He will be confronted with a series of choices about his role in the effort to undo the changes wrought by the Confederacy – an effort that, as it turns out, may rely less on violent action, and more on the presence of the Wrong Man at the Right Time…….

‘Bring’ is regarded as a classic of alternate history / time travel SF. But in reality, I found it dull and plodding.

Author Moore decides to adopt a prose style that mimics the labored diction of 19th century novels: ‘As before in my discourses with Tyss on the subject of the free will and its illusory influence on the fate of the unknowing individual, my arguments in opposition to this stance brought little more than dismissive remarks from my employer…..’

This ponderous, wordy writing style, when combined with the fact that the crucial stages of the plot don’t unfold until page 206 arrives, essentially turn ‘Jubliee’ into a tedious exposition on the social and moral aspects of a 1940s – 1950s American society permanently mired in a 19th Century mindset.

Those few moments of action or drama that do pop up in the narrative are scant, and do little to impart momentum to a plot that consists almost entirely of conversations about philosophy and metaphysics, or the main character’s internal monologues on Life, Love, and Destiny.

The closing pages of the novel are its best feature, and the author is to be credited with avoid too pat an ending. However, it’s clear that Moore missed his chance to write a genuinely ‘modern’ novel about destiny, time travel, and alternate history. Instead of being a ‘breakthrough’ novel, ‘Bring’ is simply a conventional novel with a bit of sf content.

1 / 5 Stars

'Bring the Jubilee’ first was published in 1953; this Avon SF paperback version (222 pp.) was published in May, 1972. The cover artist is uncredited.

The novel opens with an intriguing statement: Hodge Blackmaker, the first-person narrator, is writing this - his memoir - in 1877. However, he was born in 1921. How did Hodge Blackmaker come to be writing his memoir decades before he even was born ?

The opening chapters disclose the circumstances of Blackmaker’s birth and upraising: born the only child of a dour couple of modest means, living in the town of Wappingers Falls, New York. In this ‘alternity’ of the US, the Union was defeated at Gettysburg, and the Confederacy triumphed in the Civil War.

The twenty-six states of the federal government are economically and culturally backward, akin to the plight of the Southern states in the post-Civil War era of ‘our’ timeline. European powers exploit the states of the Northeast, a state of affairs endorsed by the South, which, even as it prospers, has little interest in improving the lot of the defeated Yankees. For the overwhelming majority of US citizens, a joyless lifetime of indentured servitude is the best they can hope to attain.

With aspirations to find a calling more rewarding than scrabbling for a living from farming, the teenaged Hodge leaves home for New York City, where he finds employment, and greater awareness of the depressing state of a world made real by the defeat of the Union.

As the narrative progresses, Blackmaker is introduced to the underworld of Union resistance in a New York City where it's the early 1940s, and the Second World War has never happened. He will be confronted with a series of choices about his role in the effort to undo the changes wrought by the Confederacy – an effort that, as it turns out, may rely less on violent action, and more on the presence of the Wrong Man at the Right Time…….

‘Bring’ is regarded as a classic of alternate history / time travel SF. But in reality, I found it dull and plodding.

Author Moore decides to adopt a prose style that mimics the labored diction of 19th century novels: ‘As before in my discourses with Tyss on the subject of the free will and its illusory influence on the fate of the unknowing individual, my arguments in opposition to this stance brought little more than dismissive remarks from my employer…..’

This ponderous, wordy writing style, when combined with the fact that the crucial stages of the plot don’t unfold until page 206 arrives, essentially turn ‘Jubliee’ into a tedious exposition on the social and moral aspects of a 1940s – 1950s American society permanently mired in a 19th Century mindset.

Those few moments of action or drama that do pop up in the narrative are scant, and do little to impart momentum to a plot that consists almost entirely of conversations about philosophy and metaphysics, or the main character’s internal monologues on Life, Love, and Destiny.

The closing pages of the novel are its best feature, and the author is to be credited with avoid too pat an ending. However, it’s clear that Moore missed his chance to write a genuinely ‘modern’ novel about destiny, time travel, and alternate history. Instead of being a ‘breakthrough’ novel, ‘Bring’ is simply a conventional novel with a bit of sf content.

Friday, June 13, 2014

Training Cycle by Steve Sabella

'Training Cycle' by Steve Sabella

from Epic Illustrated No. 28, February, 1985

from Epic Illustrated No. 28, February, 1985

Most of the contents of the latter issues of Epic Illustrated were mediocre, but every once in a while a real gem would get printed. Such is the case with 'Training Cycle', which features some fine artwork, and a story with a neat little twist at its ending.............

Tuesday, June 10, 2014

Cody Starbuck episodes 1 and 2

Cody Starbuck

by Howard Chaykin

Episodes 1 and 2

from Heavy Metal magazines May and June 1981

May and early June, 1981: on FM radio, 'Her Town Too' by James Taylor and J. D. Souther, is in heavy rotation.

In the May issue of Heavy Metal magazine, a new serial is underway: 'Cody Starbuck', by Howard Chaykin.

Cody Starbuck had first appeared in the very first issue of the indie comic Star Reach in April 1974, as a black-and-white comic. The character appeared again in Star Reach in 1976 and 1978.

In 1981, Chaykin produced a full color, five-part serial of Starbuck for the May - September issues of Heavy Metal.

Chaykin intended Starbuck to be a more satirical version of the space opera heroes like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. Unlike traditional sf heroes, Starbuck is decidedly amoral and self-centered, doing good deeds only if the money is right.

While such a character was essentially unmarketable in mainstream comic books of the 70s and early 80s, he was perfect for the more sophisticated, European - influenced pages of Heavy Metal.

Below, I've posted first two installments of Cody Starbuck, from Heavy Metal 's May and June 1981 issues. Stay tuned for further adventures in coming posts.

So, lets go back in time to the late Spring of 1981, give a listen to the mellow folk rock of Taylor and Souther and 'Her Town Too', and check out the doings of Cody Starbuck....

by Howard Chaykin

Episodes 1 and 2

from Heavy Metal magazines May and June 1981

In the May issue of Heavy Metal magazine, a new serial is underway: 'Cody Starbuck', by Howard Chaykin.

Cody Starbuck had first appeared in the very first issue of the indie comic Star Reach in April 1974, as a black-and-white comic. The character appeared again in Star Reach in 1976 and 1978.

In 1981, Chaykin produced a full color, five-part serial of Starbuck for the May - September issues of Heavy Metal.

Chaykin intended Starbuck to be a more satirical version of the space opera heroes like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. Unlike traditional sf heroes, Starbuck is decidedly amoral and self-centered, doing good deeds only if the money is right.

While such a character was essentially unmarketable in mainstream comic books of the 70s and early 80s, he was perfect for the more sophisticated, European - influenced pages of Heavy Metal.

Below, I've posted first two installments of Cody Starbuck, from Heavy Metal 's May and June 1981 issues. Stay tuned for further adventures in coming posts.

So, lets go back in time to the late Spring of 1981, give a listen to the mellow folk rock of Taylor and Souther and 'Her Town Too', and check out the doings of Cody Starbuck....