Book Review: 'Twistor' by John Cramer

3 / 5 Stars

‘Twistor’ first was published in 1989; this Avon Nova paperback version (338 pp) was released in November, 1991. The cover artwork is by Keith Parkinson.

In his Acknowledgement, author John Cramer indicates that the book was born from his observation that quality ‘hard’ sf was hard to find. In response, a friend challenged him to in fact write a hard sf novel, and thus, the result is ‘Twistor’.

The novel is set in Seattle, at the University of Washington Physics Department (where Cramer is, in real life, a faculty member in the department). In the laboratory of experimental physicist Alan Saxon, David Harrison, a postdoc, is working on a project to create a superconductor apparatus that exploits a (fictional) ‘holospin’ wave phenomenon derived from condensed matter physics.

If it works, the holospin superconductor will be capable of storing, and transmitting, large amounts of holographic data, revolutionizing computing and communications.

What David doesn’t know is that Saxon’s startup company is deeply in debt to the shady Megalith Corporation and its CEO, Martin Pierce. Saxon – not the most moral of individuals – is trying to wrinkle more money from Megalith by vaguely hinting at the potential financial rewards that could be unleashed if the holospin superconductor experiment proves valid.

Blinded by his own arrogance, Saxon doesn’t realize that Megalith is using all manner of clandestine actions to penetrate his subterfuges, and is on the verge of learning the true status of the work going on in the laboratory. Megalith’s goal: sell the secrets of the holospin superconductor to the world market.

Events take an unexpected turn when David Harrison conducts a late-night experiment and discovers that the superconductor field is capable of opening a portal, or ‘twistor’, to an alternate universe. Aided by the stunning, red-headed graduate student Vickie Gordon, Harrison redesigns his apparatus to expand the portal apparatus to sufficient size to accommodate human beings. But instead of embarking on a carefully prepared and executed mission, circumstances see Harrison forced through the portal, and into a strange parallel Earth.

Even as Victoria and the other graduate students and staff in the Physics Department struggle to figure out what has happened to David, Megalith makes its own move to acquire the twistor technology. And the corporation is quite willing to using violence to achieve its ends.....

‘Twistor’ succeeds as a hard sf novel. Like another hard sf novel, Benford’s ‘Timescape’ (1980), the details of actually dealing with the nuts and bolts of experimental physics are clearly communicated: David Harrison and Victoria Gordon don't stand around in white lab coats inside a gleaming,movie-set-style laboratory where a small army of hired help does all the dirty work to the rows of high-tech massive instruments, leaving the physicists to manipulate a control console and utter learned remarks.

Rather, the postdocs and grad students spend much of their time tinkering and troubleshooting their home-built contraptions. They are are part electrical engineers, part programmers, part machinists, part electricians, and, arching over all these trades and tasks, physicists. Cramer makes clear that in academia, building an apparatus and getting it to work is only a part of the larger scheme of dealing with the need to apply for, and obtain, funding to support all the activities that take place in the laboratory.

‘Twistor’ does have its weaknesses. The book is too long by about 30 – 40 pages; better editing would have seen the elimination of a cutesy sub-plot, involving a fairy tale, that serves more as filler than a vital component of the narrative.

There also are too many passages that awkwardly explore the personal interactions among the main characters; one gets the impression that the author was advised to include these in an effort to inject ‘human interest’ into the novel, lest it become a predictably dry recitation of scientific activities. And the novel closes by invoking the standard-issue trope that only Knowledge Shared can liberate Humanity from its conflicts and close-mindedness; a less Pollyanna-ish attitude would have lent the book the darker, grittier edge it needs to really stand out.

If you’re a fan of hard sf, or if you’re someone who remembers doing experimental physics research back in the day when MacSE computers, VAX terminals, and BitNet were new and exciting, then ‘Twistor’ is worth picking up.

SO....what's a PorPor Book ? 'PorPor' is a derogatory term my brother used, to refer to the SF and Fantasy paperbacks and comic books I eagerly read from the late 60s to the late 80s. This blog is devoted to those paperbacks and comics you can find on the shelves of second-hand bookstores...from the New Wave era and 'Dangerous Visions', to the advent of the cyberpunks and 'Neuromancer'. And with a leavening of pop culture detritus, too !

Monday, September 29, 2014

Friday, September 26, 2014

The Black Terror by Smith, Dixon, and Brereton

The Black Terror

Beau Smith, Chuck Dixon, Dan Brereton

Eclipse Comics, 1990

'The Black Terror' was a costumed crime-fighter who first appeared in 1941 in Exciting Comics; since that time, the rights to the character have passed through a seemingly endless number of indie comics companies. The most recent incarnation of the character is in a webcomic titled 'Curse of the Black Terror'.

In 1990 indie publisher Eclipse Comics acquired the rights to the character, part of the company's strategy of issuing superhero titles based on Golden Age properties, such as Airboy.

'The Black Terror' appeared as a three-issue prestige format series during October, 1989 (issue 1), March, 1990 (issue 2) and June, 1990 (issue 3).

Beau Smith, Chuck Dixon, Dan Brereton

Eclipse Comics, 1990

'The Black Terror' was a costumed crime-fighter who first appeared in 1941 in Exciting Comics; since that time, the rights to the character have passed through a seemingly endless number of indie comics companies. The most recent incarnation of the character is in a webcomic titled 'Curse of the Black Terror'.

In 1990 indie publisher Eclipse Comics acquired the rights to the character, part of the company's strategy of issuing superhero titles based on Golden Age properties, such as Airboy.

'The Black Terror' appeared as a three-issue prestige format series during October, 1989 (issue 1), March, 1990 (issue 2) and June, 1990 (issue 3).

The Eclipse Comics series was written by Beau Smith and Chuck Dixon. The artist, who supplied painted artwork, was Dan Brereton.'The Black Terror' was his first major comic book assignment. Brereton has since gone on to be one of most well-known contemporary comic book artists, one of the more celebrated examples of his work being DC's Thrillkiller.

In the Eclipse Comics series, the Black Terror is one Ryan Delvecchio, who is working as hired muscle for a Chicago crime syndicate headed by Anthony Capone, descendent of Al Capone.

Capone has corrupted the entire political establishment of Illinois (remember, these were the days before Rod Blagojevich), and the clandestine crime-fighting organization that Delvecchio works for is convinced that Capone has ambitions to take control of the economy of the entire country.

By day, Delvecchio works alongside Frankie Dio, the psychopathic enforcer for the Capone family. Together, he and Dio track down and punish squealers and embezzlers who have earned the wrath of the Capone family. At night, donning the garb of The Black Terror, Delvecchio rousts criminals and sleazeballs, grilling them in the hope of uncovering Capone's plans.

'The Black Terror' is first and foremost a crime comic rather than a superhero comic; the focus is on mood and atmosphere and a (rather incoherent) plot. On the whole, Brereton's artwork, relying heavily on blacks, grays, and splashes of incongruous color, works best in this sort of milieu. The few fight scenes that occupy the trilogy tend to come across as static and inert.

In keeping with the dedicated Noir atmosphere of 'The Black Terror', there is a femme fatale in the form of Anthony Capone's daughter Allison. Brereton ably represents her as a sort of quasi-Goth chick, in an early 90s style......

If you are a fan of Brereton's artwork, or a fan of crime comics with a 'retro', Noir-ish aesthetic, then 'The Black Terror' is worth getting. While a graphic novel compiling the three-issue series has never been released, full sets of the all three comics can be obtained for reasonable prices at your usual dealers.

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

Book Review: The Spell Sword

Book Review: 'The Spell Sword: A Darkover Novel' by Marion Zimmer Bradley

2 / 5 Stars

‘The Spell Sword: A Darkover Novel’ (158 pp.) first was published by DAW Books (No. 119) in September, 1974, with a cover by George Barr. In 1977 DAW issued a second printing, with excellent cover art by Richard Hescox.

As the novel opens Andrew Carr, a crewmember who serves on Terran merchant starships, is the sole survivor of the crash of a mapping and survey plane in the snow-swept cliffs of the Khilgard Hills. Injured, and unable to send off a distress signal to the far-off Terran office on Darkover, Carr struggles to stay alive in the freezing, crumpled wreckage of the plane’s fuselage. There, Carr experiences psychic sendings from a young Darkovan woman named Callista, who is apparently imprisoned somewhere in the valley below. Guided by Callista, Andrew Carr finds shelter and survival amid the cutting gusts and subzero temperatures of the mountain.

Another plot thread deals with the travails of Damon Ridenow, a Comyn nobleman who is traveling on a mission of urgency to the stronghold of Armida in the valley below the Khilgard Hills. Damon’s party is attacked and decimated by invisible assailants, and only Damon survives the carnage and arrives safely at Armida. There, he learns that Callista, daughter of Dom Esteban, and a ‘keeper’ gifted with psychic powers, has been abducted by unknown adversaries and is imprisoned in the foreboding Dark Lands beyond the boundaries of Dom Esteban’s holdings.

As the separate paths of Andrew Carr and Damon Ridenow converge, it emerges that Carr – despite being an off-worlder – possess a unique psychic capability of his own, for he, and he alone, is capable of telepathic communication with Callista. As Callista’s fate grows ever more precarious, Damon must instruct Carr in the mysteries and uses of Darkover’s psi-powers. For a rescue party is to be dispatched to search for Callista – a rescue mission that can only lead to a bloody confrontation with the cat-people who rule the Dark Lands…..

‘The Spell Sword’ starts off on a promising note, with the stranded Terran officer’s fight for survival in a hostile landscape; a damsel in distress; and a bloody sword battle between humans and mutants. The opening chapters would thus seem well-crafted to lend momentum to the remainder of the narrative, but unfortunately, author Bradley allows the momentum to rapidly dissipate by launching into extended discourses on the scientific and spiritual underpinnings of the telepathic powers wielded by the various characters, and their role in the evolution and history of Darkover culture and society.

The closing chapters do feature a return to a more action-filled narrative, but not without some contrivances, involving a sort of benign ‘possession’ that helps to equalize the odds between the Darkover rescue party and the awaiting cat-people.

In summary, ‘The Spell Sword’ is just another middling-quality Darkover novel. It’s obviously something that fans of the series will want to read, but for all others, it is strictly optional.

‘The Spell Sword: A Darkover Novel’ (158 pp.) first was published by DAW Books (No. 119) in September, 1974, with a cover by George Barr. In 1977 DAW issued a second printing, with excellent cover art by Richard Hescox.

As the novel opens Andrew Carr, a crewmember who serves on Terran merchant starships, is the sole survivor of the crash of a mapping and survey plane in the snow-swept cliffs of the Khilgard Hills. Injured, and unable to send off a distress signal to the far-off Terran office on Darkover, Carr struggles to stay alive in the freezing, crumpled wreckage of the plane’s fuselage. There, Carr experiences psychic sendings from a young Darkovan woman named Callista, who is apparently imprisoned somewhere in the valley below. Guided by Callista, Andrew Carr finds shelter and survival amid the cutting gusts and subzero temperatures of the mountain.

Another plot thread deals with the travails of Damon Ridenow, a Comyn nobleman who is traveling on a mission of urgency to the stronghold of Armida in the valley below the Khilgard Hills. Damon’s party is attacked and decimated by invisible assailants, and only Damon survives the carnage and arrives safely at Armida. There, he learns that Callista, daughter of Dom Esteban, and a ‘keeper’ gifted with psychic powers, has been abducted by unknown adversaries and is imprisoned in the foreboding Dark Lands beyond the boundaries of Dom Esteban’s holdings.

As the separate paths of Andrew Carr and Damon Ridenow converge, it emerges that Carr – despite being an off-worlder – possess a unique psychic capability of his own, for he, and he alone, is capable of telepathic communication with Callista. As Callista’s fate grows ever more precarious, Damon must instruct Carr in the mysteries and uses of Darkover’s psi-powers. For a rescue party is to be dispatched to search for Callista – a rescue mission that can only lead to a bloody confrontation with the cat-people who rule the Dark Lands…..

‘The Spell Sword’ starts off on a promising note, with the stranded Terran officer’s fight for survival in a hostile landscape; a damsel in distress; and a bloody sword battle between humans and mutants. The opening chapters would thus seem well-crafted to lend momentum to the remainder of the narrative, but unfortunately, author Bradley allows the momentum to rapidly dissipate by launching into extended discourses on the scientific and spiritual underpinnings of the telepathic powers wielded by the various characters, and their role in the evolution and history of Darkover culture and society.

The closing chapters do feature a return to a more action-filled narrative, but not without some contrivances, involving a sort of benign ‘possession’ that helps to equalize the odds between the Darkover rescue party and the awaiting cat-people.

In summary, ‘The Spell Sword’ is just another middling-quality Darkover novel. It’s obviously something that fans of the series will want to read, but for all others, it is strictly optional.

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Heavy Metal September 1979

'Heavy Metal' magazine September 1979

September, 1979, and selected FM radio stations are playing the song 'Hold On' by Ian Gomm.

The latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is available at Gordon's cigar store, and I eagerly pick it up.

Jim Cherry provided the front cover, ‘Love Hurts’, while the back cover is an untitled painting by Val Mayerik. There's a full-page advertisement for the Car's new album 'Candy-O', featuring a Vargas Girl sprawled atop the engine of a sports car. Crude sexual exploitation, or cool marketing ? In the 70s, they didn't really care.....

The September, 1979 issue is a good issue, with 'Only Connect: The Spirit of the Game' by Alias, 'The Doll' by J. K. Potter, 'Little Red' by He, 'Soft Landing' by Warkentin and O'Bannon, 'Airtight Garage' by Moebius, and 'Telefield' by Sergio Macedo.

Among the better comics was a one-and-only episode of 'Buck Rogers in the 25th Century: On the Moon of Madness' by Gray Morrow and Jim Lawrence. I've posted it below.

September, 1979, and selected FM radio stations are playing the song 'Hold On' by Ian Gomm.

The latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is available at Gordon's cigar store, and I eagerly pick it up.

Jim Cherry provided the front cover, ‘Love Hurts’, while the back cover is an untitled painting by Val Mayerik. There's a full-page advertisement for the Car's new album 'Candy-O', featuring a Vargas Girl sprawled atop the engine of a sports car. Crude sexual exploitation, or cool marketing ? In the 70s, they didn't really care.....

The September, 1979 issue is a good issue, with 'Only Connect: The Spirit of the Game' by Alias, 'The Doll' by J. K. Potter, 'Little Red' by He, 'Soft Landing' by Warkentin and O'Bannon, 'Airtight Garage' by Moebius, and 'Telefield' by Sergio Macedo.

Among the better comics was a one-and-only episode of 'Buck Rogers in the 25th Century: On the Moon of Madness' by Gray Morrow and Jim Lawrence. I've posted it below.

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Scout Volume One

Scout

Volume One

by Tim Truman

Dynamite Entertainment, 2006

Scripted and drawn by Tim Truman, the first issue of ‘Scout’ was published by the Indie publisher Eclipse Comics in September, 1985, and ran for 24 issues until October, 1987.

The eponymous Scout was an Apache Indian named Emanuel Santana (Truman is an avid fan of rock musician Carlos Santana). The series was set in the near future, i.e., ca. 1999, and the USA is in bad shape, beset with economic collapse, eco-disasters, widespread political corruption, and, in the cities, anarchy and lawlessness.

While Eclipse issued graphic novels compiling the 'Scout' series, those volumes are long out of print. In 2006 Dynamite Entertainment released the first 16 issues of 'Scout' in two trade paperback compilations; volume one compiled issues 1-7, and volume two, 8 – 15. The comics in these compilations have been recolored and ‘remastered’ (whatever that means.....?).

Volume One

by Tim Truman

Dynamite Entertainment, 2006

Scripted and drawn by Tim Truman, the first issue of ‘Scout’ was published by the Indie publisher Eclipse Comics in September, 1985, and ran for 24 issues until October, 1987.

The eponymous Scout was an Apache Indian named Emanuel Santana (Truman is an avid fan of rock musician Carlos Santana). The series was set in the near future, i.e., ca. 1999, and the USA is in bad shape, beset with economic collapse, eco-disasters, widespread political corruption, and, in the cities, anarchy and lawlessness.

While Eclipse issued graphic novels compiling the 'Scout' series, those volumes are long out of print. In 2006 Dynamite Entertainment released the first 16 issues of 'Scout' in two trade paperback compilations; volume one compiled issues 1-7, and volume two, 8 – 15. The comics in these compilations have been recolored and ‘remastered’ (whatever that means.....?).

Volume 1 features an Introduction from John Ostrander, Truman's writer for the 'Grimjack' comic book series from the mid-80s. There also is a interview with Truman that serves as the book's Afterword; in the interview, Truman admits that he initially was reluctant to see his 'Scout' comics compiled and reprinted, because he was ambivalent about the quality of his draftsmanship back in those long-ago days.

Be that as it may be, I find the artwork in 'Scout' to be well done, and, as always, a relief from the 'line-drawing' aesthetic, designed to accommodate computer scanning and coloring, that dominates comic book artwork nowadays.

The color separations are not ideal - the book's original printing technology is of course nearly 30 years old- and leave the panels with a 'murky' look, but again, I'll take it over the artificial appearance of the color in so many of today's comic books.

I won't disclose any spoilers regarding the plot of these first issues of 'Scout', save to say that our hero embarks on a quasi-spiritual quest to identify and eliminate four monsters, beings drawn from ancient Apache mythology. These four monsters have taken on human guise, and all work cooperatively to take over the nation and use it for their own nefarious ends.

As an Apache, Scout is the prototypical loner, a man of few words. The narrative is suffused with a worshipful attitude towards Native American Wisdom, and at times this veers into Noble Savage territory, particularly when coupled with the author's (self-admittedly white liberal) left-wing take on the political and corporate establishments that have exploited and despoiled this near-future USA.

However, Truman provides enough sarcastic humor throughout the book to sufficiently lighten the mood, and prevent the arrival of a preachy or sententious atmosphere.

The first six issues of 'Scout' served as a complete story arc; issue 7, included in this volume, is a 'flashback' episode with very nice artwork from substitute artist Tom Yeates (Truman was on paternity leave). I confess to being unfamiliar with Yeates's work, but his illustrations for The Outlaw Prince series have received high praise.

Summing up, whether you're a fan of well-told and well-illustrated comics with a 'Mad Max' type of atmosphere, or whether you're a fan of Truman's graphic work, a copy of 'Scout: Volume One' is well worth getting.

[Volume Two complies issues 8 - 15; however, it's unclear of the remaining contents of the series - i.e., issues 16 - 24 - are going to be issued in a graphic novel from Dynamite.]

The color separations are not ideal - the book's original printing technology is of course nearly 30 years old- and leave the panels with a 'murky' look, but again, I'll take it over the artificial appearance of the color in so many of today's comic books.

I won't disclose any spoilers regarding the plot of these first issues of 'Scout', save to say that our hero embarks on a quasi-spiritual quest to identify and eliminate four monsters, beings drawn from ancient Apache mythology. These four monsters have taken on human guise, and all work cooperatively to take over the nation and use it for their own nefarious ends.

As an Apache, Scout is the prototypical loner, a man of few words. The narrative is suffused with a worshipful attitude towards Native American Wisdom, and at times this veers into Noble Savage territory, particularly when coupled with the author's (self-admittedly white liberal) left-wing take on the political and corporate establishments that have exploited and despoiled this near-future USA.

However, Truman provides enough sarcastic humor throughout the book to sufficiently lighten the mood, and prevent the arrival of a preachy or sententious atmosphere.

The first six issues of 'Scout' served as a complete story arc; issue 7, included in this volume, is a 'flashback' episode with very nice artwork from substitute artist Tom Yeates (Truman was on paternity leave). I confess to being unfamiliar with Yeates's work, but his illustrations for The Outlaw Prince series have received high praise.

Summing up, whether you're a fan of well-told and well-illustrated comics with a 'Mad Max' type of atmosphere, or whether you're a fan of Truman's graphic work, a copy of 'Scout: Volume One' is well worth getting.

[Volume Two complies issues 8 - 15; however, it's unclear of the remaining contents of the series - i.e., issues 16 - 24 - are going to be issued in a graphic novel from Dynamite.]

Monday, September 15, 2014

Book Review: Eyas

Book Review: 'Eyas' by Crawford Killian

4 / 5 Stars

‘Eyas’ (354 pp) first was published in August 1982 by Bantam Books; the cover artist is uncredited. The Del Rey Books version (357 pp) was released in March, 1989 and features a fine cover illustration by Steve Hickman.

The novel is set some 10 million years into the future. While California has fallen into the Pacific, the rest of the continent of North America remains intact. Man shares the continent with mutant humanoids; the centaurs live in the Midwest, while the lotors, a race descended from weasels, occupy the southern regions. A race of flying humanoids, called the Windwalkers, live on floating islands of vegetation supported by giant pea-pods filled with helium, and sail the wind currents around the world.

The opening chapters of ‘Eyas’ take place in what was British Columbia, where the ‘People’, the descendents of the Chinooks, continue to live a simple but fulfilling life centered on fishing and hunter-gathering. During the yearly gathering of the tribes, the small fishing vessel of Darkhair Fisher, a stalwart member of the tribe of the village of Longstrand, ventures into the mouth of the inland sea where it empties into the Pacific, and comes upon a large sailing vessel – a type of ship never before seen by the People.

As Fisher looks on, the sailing ship wrecks upon the rocks; after much effort, only three people are saved from its complement: the young boys Brighteyes and Eyas, and the young woman Silken. It is revealed that the ship and crew originated from the nation of Sun, far to the East, in what is nowadays western Texas, and was in desperate flight from another Sunnish vessel.

Darkhair makes a momentous decision: he will not only provide shelter to the trio of Suns, but his family will rear the boy Eyas as one of their own, while Silken elects to raise Brightspear.

As the boys mature, Darkhair comes to realize that the world of the People is much smaller and more insignificant than he has ever imagined. Far inland, the Suns make constant, merciless war on the other races of the continent, seeking new lands to sustain their ever-growing population. Brightspear is in fact the disinherited son of a Sun chieftan, and he will seek to reclaim his kingdom as an adult.

But so doing will bring him into conflict with Eyas, for he alone realizes that the advance of the Suns can only be stopped by an unprecedented alliance of Man and Mutants.

As the two men reach adulthood, the world of the People, and indeed North America, will be caught up in a war unlike any that has taken place before. And for Eyas, the key to victory will be understanding the strange artifacts of the Gods, artifacts that lie far, far above in the blue skies over the Earth……...

‘Eyas’ is a very readable novel. The conflict between the two Suns, Eyas and Brightspear, drives the narrative, and throughout much of its second half, ‘Eyas’ is really more of a military adventure with sf overtones. There is a large cast of characters, but the author shows skill in allowing them to be fully realized without overwhelming the storyline.

There are a couple of weaknesses to ‘Eyas’, and these are the reasons I couldn’t give the novel a five-star rating. One weakness is the inclusion of a subplot dealing with messages and premonitions from the dead – apparently in Hell – that are ‘beamed’ to Eyas and some of the other characters. As the plot unfolds, this metaphysical element comes to occupy more and more the narrative, and it meshes poorly with the othwerwise straightforward, realistic elements of the plot.

Another weakness has to do with the Cosmic Revelations that are hinted at early on in ‘Eyas’. In the final three chapters these Revelations make their appearance, but the sf tropes associated with them come so fast, and so glibly, that the novel’s denouement suffers as a result.

Still, when all is said and done, ‘Eyas’ is one of the best sf novels of the early 80s; no small achievement when one remembers that sf at that time was in the doldrums, and quality short stories and novels were few and far between.

4 / 5 Stars

‘Eyas’ (354 pp) first was published in August 1982 by Bantam Books; the cover artist is uncredited. The Del Rey Books version (357 pp) was released in March, 1989 and features a fine cover illustration by Steve Hickman.

The novel is set some 10 million years into the future. While California has fallen into the Pacific, the rest of the continent of North America remains intact. Man shares the continent with mutant humanoids; the centaurs live in the Midwest, while the lotors, a race descended from weasels, occupy the southern regions. A race of flying humanoids, called the Windwalkers, live on floating islands of vegetation supported by giant pea-pods filled with helium, and sail the wind currents around the world.

The opening chapters of ‘Eyas’ take place in what was British Columbia, where the ‘People’, the descendents of the Chinooks, continue to live a simple but fulfilling life centered on fishing and hunter-gathering. During the yearly gathering of the tribes, the small fishing vessel of Darkhair Fisher, a stalwart member of the tribe of the village of Longstrand, ventures into the mouth of the inland sea where it empties into the Pacific, and comes upon a large sailing vessel – a type of ship never before seen by the People.

As Fisher looks on, the sailing ship wrecks upon the rocks; after much effort, only three people are saved from its complement: the young boys Brighteyes and Eyas, and the young woman Silken. It is revealed that the ship and crew originated from the nation of Sun, far to the East, in what is nowadays western Texas, and was in desperate flight from another Sunnish vessel.

Darkhair makes a momentous decision: he will not only provide shelter to the trio of Suns, but his family will rear the boy Eyas as one of their own, while Silken elects to raise Brightspear.

As the boys mature, Darkhair comes to realize that the world of the People is much smaller and more insignificant than he has ever imagined. Far inland, the Suns make constant, merciless war on the other races of the continent, seeking new lands to sustain their ever-growing population. Brightspear is in fact the disinherited son of a Sun chieftan, and he will seek to reclaim his kingdom as an adult.

But so doing will bring him into conflict with Eyas, for he alone realizes that the advance of the Suns can only be stopped by an unprecedented alliance of Man and Mutants.

As the two men reach adulthood, the world of the People, and indeed North America, will be caught up in a war unlike any that has taken place before. And for Eyas, the key to victory will be understanding the strange artifacts of the Gods, artifacts that lie far, far above in the blue skies over the Earth……...

‘Eyas’ is a very readable novel. The conflict between the two Suns, Eyas and Brightspear, drives the narrative, and throughout much of its second half, ‘Eyas’ is really more of a military adventure with sf overtones. There is a large cast of characters, but the author shows skill in allowing them to be fully realized without overwhelming the storyline.

There are a couple of weaknesses to ‘Eyas’, and these are the reasons I couldn’t give the novel a five-star rating. One weakness is the inclusion of a subplot dealing with messages and premonitions from the dead – apparently in Hell – that are ‘beamed’ to Eyas and some of the other characters. As the plot unfolds, this metaphysical element comes to occupy more and more the narrative, and it meshes poorly with the othwerwise straightforward, realistic elements of the plot.

Another weakness has to do with the Cosmic Revelations that are hinted at early on in ‘Eyas’. In the final three chapters these Revelations make their appearance, but the sf tropes associated with them come so fast, and so glibly, that the novel’s denouement suffers as a result.

Still, when all is said and done, ‘Eyas’ is one of the best sf novels of the early 80s; no small achievement when one remembers that sf at that time was in the doldrums, and quality short stories and novels were few and far between.

Friday, September 12, 2014

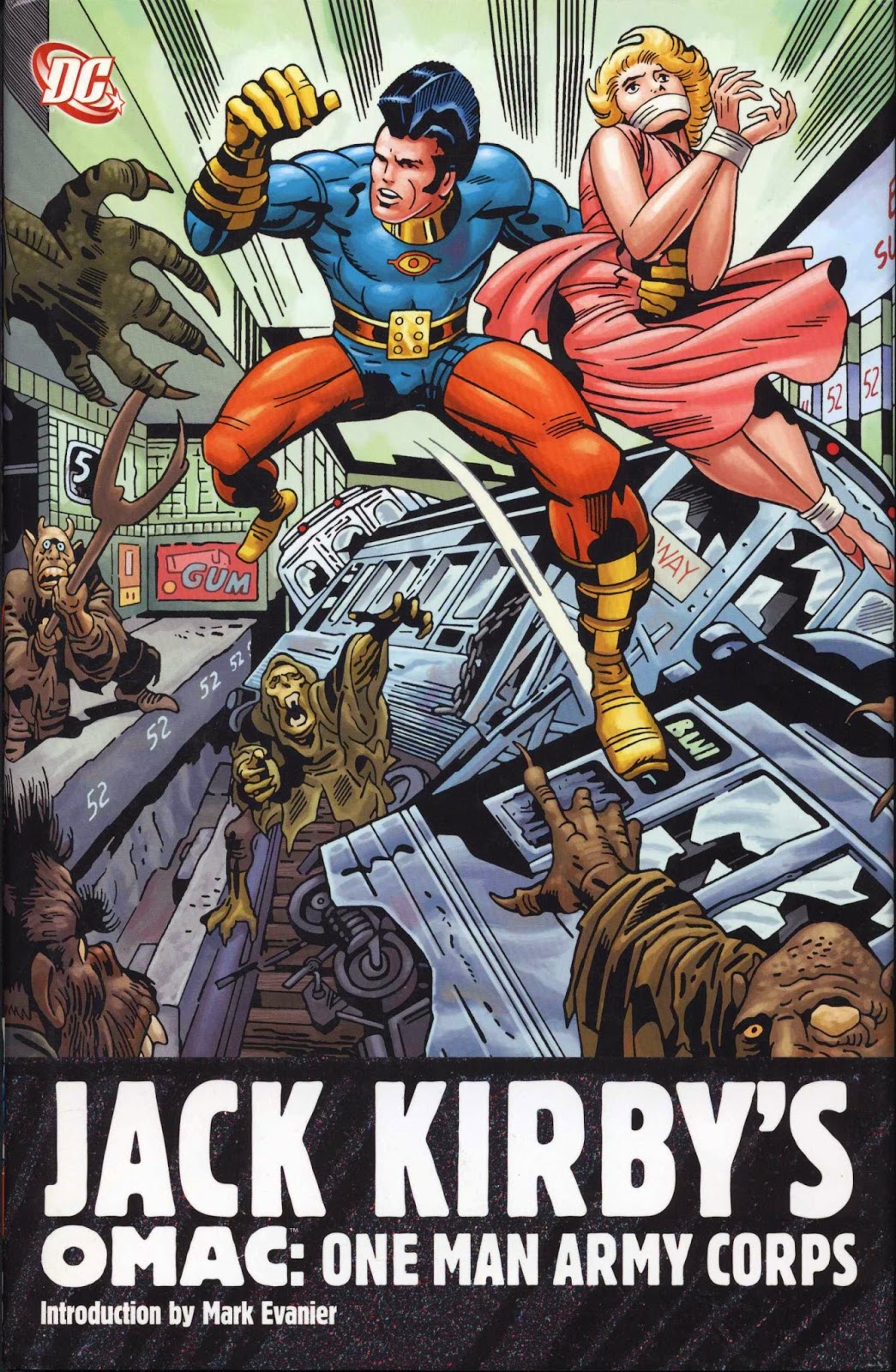

Jack Kirby's OMAC

Jack Kirby's OMAC: One Man Army Corps

This 200-page hardbound volume, published in June, 2008 by DC Comics, contains all the issues of 'OMAC ('One Man Army Corps) that DC released, starting with issue one in September, 1974, and concluding with issue 8 in November, 1975.

'Jack Kirby's OMAC' is in full color, but uses the 'newsprint' quality paper that draws some criticism from reviewers at online venues.

The book features a Forward by Mark Evanier, who indicates that Jack Kirby first envisioned the OMAC character ca.1968, during his time at Marvel comics. Kirby evidently was interested in creating a sort of near-future manifestation of Captain America, a character whose 'Go Team USA !' attitudes would seem obsolete and inadequate to cope with a world similar to that of the one outlined in Alvin Toffler's 1970 book Future Shock.

Kirby left Marvel before the idea of a 'Future Shock' Captain America progressed beyond the conceptual stage.

As Evanier relates, in 1974, DC's contract with Kirby called for him to deliver a minimum of 15 pages of completed artwork per week. Because Kammandi was doing well, DC's management suggested that Kirby do another sf-themed title, and so, Kirby recalled his concept of an updated version of Captain America from six years previously, and launched OMAC.

The opening issue introduces us to Buddy Blank, an undersized, hesistant young man who works as an errand boy in a large corporation. When Buddy stumbles on a clandestine sales operation, he is marked for elimination by his employers - until, that is, Blank becomes the target for a super-secret program: the conversion of an everyday, average citizen into OMAC, the One Man Army Corps.....

OMAC is the prime agent for justice in 'the world that's coming', an entity that reflects the Future Shock visions of a globe beset by the social upheavals wrought by the advent of new technologies.

In succeeding issues, OMAC, now an agent of the Global Peace Agency, and aided by the high-tech gadgetry of the satellite Brother Eye, takes on corrupt gangsters, megalomaniacs intent on conquering the planet, illegal body-swapping brokers, and hordes of monsters infesting the subways of New York City.

The artwork in OMAC is as good as anything Kirby did on his other titles for DC (and, considering his workload, Kirby's artwork was especially impressive). As always, Kirby's pencils (some of his draft pages are reproduced here) were ably inked by Mike Royer.

The writing is less rewarding. While most episodes start on a promising note in terms of content, with some even prefiguring cyberpunk themes a good decade before Neuromancer was published, all of the episodes seem to devolve too quickly into more traditional material, often consisting of well-choreographed, lengthy fight scenes, often with monsters reminiscent of creatures like 'Fin Fang Foom' and 'Torr' from Kirby's early 1960s comic books for Marvel.

The final two issues of OMAC show that Kirby was trying to direct the plotting into more imaginative directions, including one dealing with eco-disaster, and an awareness that OMAC was not invincible, nor always assured of victory. Unfortunately, the series was cancelled by DC after Kirby made a decision to return to Marvel in 1976.

Summing up, I really don't think 'Jack Kirby's OMAC' is sophisticated enough to appeal to modern comic book readers. The book is directed more towards those over 45 who are nostalgic over those long-ago days of Kirby's titles for DC, as well as Kirby fans and completists. They are more likely to enjoy this incarnation of 'OMAC'.

This 200-page hardbound volume, published in June, 2008 by DC Comics, contains all the issues of 'OMAC ('One Man Army Corps) that DC released, starting with issue one in September, 1974, and concluding with issue 8 in November, 1975.

'Jack Kirby's OMAC' is in full color, but uses the 'newsprint' quality paper that draws some criticism from reviewers at online venues.

The book features a Forward by Mark Evanier, who indicates that Jack Kirby first envisioned the OMAC character ca.1968, during his time at Marvel comics. Kirby evidently was interested in creating a sort of near-future manifestation of Captain America, a character whose 'Go Team USA !' attitudes would seem obsolete and inadequate to cope with a world similar to that of the one outlined in Alvin Toffler's 1970 book Future Shock.

Kirby left Marvel before the idea of a 'Future Shock' Captain America progressed beyond the conceptual stage.

As Evanier relates, in 1974, DC's contract with Kirby called for him to deliver a minimum of 15 pages of completed artwork per week. Because Kammandi was doing well, DC's management suggested that Kirby do another sf-themed title, and so, Kirby recalled his concept of an updated version of Captain America from six years previously, and launched OMAC.

The opening issue introduces us to Buddy Blank, an undersized, hesistant young man who works as an errand boy in a large corporation. When Buddy stumbles on a clandestine sales operation, he is marked for elimination by his employers - until, that is, Blank becomes the target for a super-secret program: the conversion of an everyday, average citizen into OMAC, the One Man Army Corps.....

OMAC is the prime agent for justice in 'the world that's coming', an entity that reflects the Future Shock visions of a globe beset by the social upheavals wrought by the advent of new technologies.

In succeeding issues, OMAC, now an agent of the Global Peace Agency, and aided by the high-tech gadgetry of the satellite Brother Eye, takes on corrupt gangsters, megalomaniacs intent on conquering the planet, illegal body-swapping brokers, and hordes of monsters infesting the subways of New York City.

The artwork in OMAC is as good as anything Kirby did on his other titles for DC (and, considering his workload, Kirby's artwork was especially impressive). As always, Kirby's pencils (some of his draft pages are reproduced here) were ably inked by Mike Royer.

Summing up, I really don't think 'Jack Kirby's OMAC' is sophisticated enough to appeal to modern comic book readers. The book is directed more towards those over 45 who are nostalgic over those long-ago days of Kirby's titles for DC, as well as Kirby fans and completists. They are more likely to enjoy this incarnation of 'OMAC'.

Tuesday, September 9, 2014

Heavy Metal magazine September 1984

'Heavy Metal' magazine September 1984

September, 1984, and in heavy rotation on the FM radio stations is David Bowie's song 'Blue Jean'.

The August, 1984 issue of Heavy Metal magazine was bad. The September issue, unfortunately, isn't much better. It does have a striking wraround cover by Luis Royo, however.

There are new installments of Benard and Schuiten's 'The Railway'; Druillet's 'Salammbo II'; Frank Thorne's 'Lann', and John Findley's 'Tex Arcana'.

However, the rest of the content is mediocre. Kierkegaard's 'Rock Opera' persist in being published, Nicola Cuti's 'Things' is forgettable, and the most awful strip in the issue is a one-shot titled 'Sen Lubin from Ernst' by a duo named Victoria Petersen and Neal McPheeters.

Perhaps the most interesting, and surprising, article in the September issue is the Heavy Metal '1984 Music Video Awards'. After having spent the interval from 1981 - 1983 regarding music television with some degree of the dedicated hipster's disdain, the magazine's editorial staff now enthusiastically embrace music videos, and devote 8 pages to showcasing their faves for the year (loosely interpreted as 1983, and the first six months of 1984).

Some of these videos ('Every Breath You Take' by The Police) will be quite familiar to anyone who watched MTV at that time; some are a bit more obscure - I'd completely forgotten those grainy, washed-out-palette, jerkily handheld camera - imitating Neil Young rockabilly videos like 'Wonderin'.

Still other videos earning accolades from HM are utterly obscure - does anyone remember Jack the Ripper by The Raybeats ?! it's a retro surf-rock song with a spot-on video.....

In any event, below I've posted the text of Heavy Metal's 1984 Music Video Awards, so you can see for yourself what was hip and cutting-edge back in those long-ago days......

The August, 1984 issue of Heavy Metal magazine was bad. The September issue, unfortunately, isn't much better. It does have a striking wraround cover by Luis Royo, however.

There are new installments of Benard and Schuiten's 'The Railway'; Druillet's 'Salammbo II'; Frank Thorne's 'Lann', and John Findley's 'Tex Arcana'.

However, the rest of the content is mediocre. Kierkegaard's 'Rock Opera' persist in being published, Nicola Cuti's 'Things' is forgettable, and the most awful strip in the issue is a one-shot titled 'Sen Lubin from Ernst' by a duo named Victoria Petersen and Neal McPheeters.

Some of these videos ('Every Breath You Take' by The Police) will be quite familiar to anyone who watched MTV at that time; some are a bit more obscure - I'd completely forgotten those grainy, washed-out-palette, jerkily handheld camera - imitating Neil Young rockabilly videos like 'Wonderin'.

Still other videos earning accolades from HM are utterly obscure - does anyone remember Jack the Ripper by The Raybeats ?! it's a retro surf-rock song with a spot-on video.....

In any event, below I've posted the text of Heavy Metal's 1984 Music Video Awards, so you can see for yourself what was hip and cutting-edge back in those long-ago days......