Book Review: 'When Gravity Fails' by George Alec Effinger

4 / 5 Stars

‘When Gravity Fails’ first was published in hardback in 1986; this paperback edition (276 pp) was published by Bantam Books / Spectra in January, 1988. The cover art is by Jim Burns.

‘When Gravity Fails’ is the first book in the ‘Marid Audran’ trilogy, with the succeeding volumes ‘A Fire in the Sun’ (1989) and ‘The Exile Kiss’ (1991). A collection of related short stories, titled ‘Budayeen Nights’, was released in 2003.

‘When Gravity Fails’ can rightfully be considered a First Generation Cyberpunk novel, one standing alongside Neuromancer, Dr. Adder, Hardwired, and Metrophage….. although, curiously, it doesn’t appear on at least one of the more comprehensive lists of novels of the Cyberpunk Canon.

‘Gravity’ certainly can be regarded as the first novel to mix cyberpunk with the detective / private eye novel; it is the forerunner of such later novels as the ‘Carlucci’ series by Richard Paul Russo and Noir by K. W. Jeter.

‘Gravity’ is set in a near-future Alexandria (perhaps; it is never explicitly named as such), in the red-light district known as the Budayeen. Along with brothels, bars, shady merchants, and myriad tourist traps, the Budayeen offers a relaxed attitude towards vice and crime, albeit with the tacit approval of the authorities.

Marid Audran is a young Arab man who earns a living as a fixer and go-between among the personalities in the Budayeen. Marid’s worldly aspirations are modest:, and centered on earning enough money to maintain an apartment, a girlfriend, regular forays into the local night life, and a drug habit.

As the novel opens, Marid has been contacted by a Russian exile, who is seeking to hire someone to find his son, presumed to be in hiding among the narrow streets and alleys of the Budayeen. Hardly has the meeting between the Russian exile and Marid begun, then events take a violent turn. What at first seems to be a random series of particularly brutal, sadistic murders may in fact be the work of a serial killer, and Marid’s friends and acquaintances may be among his prey.

When Friedlander Bey, the ‘big boss’ of the Budayeen, decides that the murders are disrupting the district’s profitability, he approaches Marid with an offer that is not meant to be refused. For Bey wants Marid to be surgically altered, outfitted with neural implants that accept ‘mods’ – computer chips containing personality profiles of persons both real, and fictitious. Once equipped with his new implants, Marid’s task is to track down and eliminate the killer. But time is running out, for there is evidence that Marid himself is next on the list for elimination…..

For the first third of its length, ‘When Gravity Fails’ is an engaging read. The near-future Budayeen, with its eclectic mix of Muslim piety and crass commercialism, is an offbeat locale, one that stands out from the generic East Asian metropolises usually encountered in cyberpunk works. The novel’s large cast of characters is handled in a deft manner , and the incorporation of the private eye / noir elements of the plot is done with the right notes of sardonic humor.

Unfortunately, the middle segments of the book lose momentum, as the author shifts attention from the unfolding of the main plot, to examine - in some lengthy expositions - Marid Audran’s psychological and emotional travails. The final third of the book sees the narrative refocus on the murder mystery driving the plot, but it’s a case of too little, too late, and I found that the resolution of the mystery had a contrived quality. It also didn’t help matters when Effinger’s final-chapter efforts to tie together all of the various red herrings and side plots was confusing, rather than enlightening. To be fair, a lot of private eye novels suffer from this same defect, so I can’t over-criticize ‘When Gravity Fails’ for this defect.

When all is said and done, ‘When Gravity Fails’ is a Four Star read, and a good entry into the Cyberpunk Canon. If you’re a fan of that genre, you’ll want to have it in your collection.

SO....what's a PorPor Book ? 'PorPor' is a derogatory term my brother used, to refer to the SF and Fantasy paperbacks and comic books I eagerly read from the late 60s to the late 80s. This blog is devoted to those paperbacks and comics you can find on the shelves of second-hand bookstores...from the New Wave era and 'Dangerous Visions', to the advent of the cyberpunks and 'Neuromancer'. And with a leavening of pop culture detritus, too !

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Sunday, April 24, 2016

Nuclear Disaster Novels

Nuclear Disaster Novels

With the arrival of the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster, I thought I'd highlight one of the more offbeat sub-genres of sf: the nuclear disaster novel. Here are the ones in my collection, and - for those I've read - a brief summary, and a link to my full review.

Dome in its Pocket Books (1979, bottom) and New English Library (1980, top) versions. I haven't read this one. The plot has to do with a reactor disaster in the Southern USA.

Hapless Canadians confront the meltdown of a nuke plant near Toronto. I reviewed this one and gave it four stars.

This 1985 book was one of the Ace Science Fiction Specials. One hundred years after Three Mile Island underwent a meltdown in March of 1979, a vast chunk of Pennsylvania is inhabited only by outlaws and mutants. I gave this novel four stars.

Del Rey's 1956 novel is the earliest treatment of the theme in sf, but that's about the only noteworthy thing about it. Nerves is poorly written and at times incomprehensible. I gave it one star.

This one is not easy to find. The original hardcover was published in 1974 as Paradigm Red. When the TV adaptation, titled Red Alert, was aired in 1977, Pocket Books released it as the above paperback.

This is a 1979 English translation of the 1976 German novel Die Explosion. I haven't read it.

In the USA of the future, unregulated nuke plant construction has left most of the country exposed to radioactivity from accidents and waste. I gave this novel four stars.

A nuke disaster strikes southern California. Although the disaster itself doesn't take place until half-way through this lengthy novel, it's a well-written account of a meltdown, and I gave it four stars.

With the arrival of the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster, I thought I'd highlight one of the more offbeat sub-genres of sf: the nuclear disaster novel. Here are the ones in my collection, and - for those I've read - a brief summary, and a link to my full review.

Dome in its Pocket Books (1979, bottom) and New English Library (1980, top) versions. I haven't read this one. The plot has to do with a reactor disaster in the Southern USA.

Hapless Canadians confront the meltdown of a nuke plant near Toronto. I reviewed this one and gave it four stars.

This 1985 book was one of the Ace Science Fiction Specials. One hundred years after Three Mile Island underwent a meltdown in March of 1979, a vast chunk of Pennsylvania is inhabited only by outlaws and mutants. I gave this novel four stars.

Del Rey's 1956 novel is the earliest treatment of the theme in sf, but that's about the only noteworthy thing about it. Nerves is poorly written and at times incomprehensible. I gave it one star.

This one is not easy to find. The original hardcover was published in 1974 as Paradigm Red. When the TV adaptation, titled Red Alert, was aired in 1977, Pocket Books released it as the above paperback.

This is a 1979 English translation of the 1976 German novel Die Explosion. I haven't read it.

In the USA of the future, unregulated nuke plant construction has left most of the country exposed to radioactivity from accidents and waste. I gave this novel four stars.

A nuke disaster strikes southern California. Although the disaster itself doesn't take place until half-way through this lengthy novel, it's a well-written account of a meltdown, and I gave it four stars.

Thursday, April 21, 2016

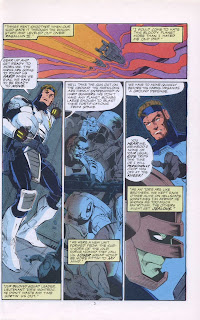

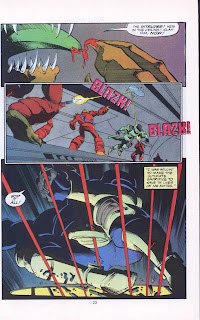

Alien Legion: The Ditch

Alien Legion: The Ditch

by Chuck Dixon (writer) and Larry Stroman (art)

Alien Legion No. 5, June 1988

Epic / Marvel

Alien Legion was launched by Marvel's Epic Comics imprint in 1984, with The Alien Legion issues 1 - 20 released in 1984 - 1987. Eighteen issues of a second series, somewhat confusingly titled simply Alien Legion, was released during 1987 - 1990.

One of the more entertaining characters in the Legion - which creator Carl Potts envisioned as 'the Foreign Legion in space' - was Jugger Grimrod, a genuine 'grunt' perpetually in danger of being booted out for insubordination.

In this standalone tale from issue 5 of the second series, Grimrod finds himself alone and abandoned on a hostile planet.......the consequence of yet another screwup by the High Command. But, aided by plentiful amounts of mud and blood, Grimrod finds a way to overcome all obstacles and complete the mission. It's fast-moving adventure, with lots of sarcastic humor, and good artwork by Larry Stroman.

by Chuck Dixon (writer) and Larry Stroman (art)

Alien Legion No. 5, June 1988

Epic / Marvel

Alien Legion was launched by Marvel's Epic Comics imprint in 1984, with The Alien Legion issues 1 - 20 released in 1984 - 1987. Eighteen issues of a second series, somewhat confusingly titled simply Alien Legion, was released during 1987 - 1990.

One of the more entertaining characters in the Legion - which creator Carl Potts envisioned as 'the Foreign Legion in space' - was Jugger Grimrod, a genuine 'grunt' perpetually in danger of being booted out for insubordination.

In this standalone tale from issue 5 of the second series, Grimrod finds himself alone and abandoned on a hostile planet.......the consequence of yet another screwup by the High Command. But, aided by plentiful amounts of mud and blood, Grimrod finds a way to overcome all obstacles and complete the mission. It's fast-moving adventure, with lots of sarcastic humor, and good artwork by Larry Stroman.

Sunday, April 17, 2016

Book Review: The Truth About Chernobyl

Book Review: 'The Truth About Chenobyl' by Grigori Medvedev

3 / 5 Stars

I remember when I first heard about the disaster at Chernobyl: it was on Tuesday, April 29, 1986. I was a graduate student at Louisiana State University at the time, and I was sitting in the barber shop in the Student Union, and a morning news program - I forget which one - was playing on the television mounted on the wall of the shop. The anchor announced that an accident had occurred at a nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union.

The coverage of the Chernobyl accident being broadcast on the televisions and newspapers in the United States was limited, and mainly comprised of rumor; this was back before there was an internet, or Twitter, or Facebook, and it was much easier for the Soviet government to hide the scope of the disaster. But it was quite obvious that something disastrous had happened in the Soviet Union, and as more details began to emerge over the following weeks, it became clear that the world's worst nuclear disaster had taken place.

On the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, I thought I would read one of the first books that addressed the phenomenon: Grigori Medvedev's The Truth About Chernobyl, which first was published in 1989 in Russia, followed by this English language translation (274 pp.; Basic Books) which was released in 1991.

The capsule summary: early in the morning of April 26, 1986, there was a catastrophic explosion of Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant at Pripyat, Ukraine (then a part of the Soviet Union). The accident led to the release of massive amounts of radioactive particulates (400 times more than that of the Hiroshima atomic bomb detonation) into the atmosphere, with fallout covering large areas of western and northern Europe.

The plant managers initially refused to believe that the reactor had been destroyed, and told the Soviet authorities in Moscow that the plant had suffered minor damage from a turbine explosion. It wasn't until the afternoon of April 27 that the authorities began the evacuation of the entire population (approximately 50,000 people) from Pripyat.

(an excellent photoessay on the disaster is available here)

Only the self-sacrificial actions of engineers and firefighters prevented the reactor from undergoing additional, even more disastrous, explosions. Using a labor force of a quarter of a million workers, by November 1986 a concrete 'sarcophagous' was erected over the ruins of the reactor. A massive effort to collect and bury radioactive debris and soil from the areas surrounding Pripyat continued into 1987. Ukrainian officials have declared that the area around Chenobyl will not be safe for human habitation for another 20,000 years.

Grigori Medvedev was a nuclear engineer who, in 1986, was working at the Soviet government's 'Suyuzatomenergostroy' national energy directorate. Medvedev had worked at a number of nuclear power plants in the USSR, including a stint as a deputy chief engineer at Chernobyl in the 1970s; he even had been hospitalized for radiation sickness (for an exposure that he does not detail). In May, 1986, he was sent by his management to Chernobyl to investigate the situation and report back. Much of the book's contents are derived from his observations and analysis associated with that investigation.

At the time the book was published in 1989, the Soviet government had refused to release to the public the complete truth of its investigations into the causes of the accident; this despite the emphasis on 'glasnost' by the Gorbachev presidency. So much of Medvedev's book is devoted - sometimes in an oblique way - to condemning the Soviet system, which in 1989 was a risky action even for a well-regarded engineer and subject matter expert like himself.

The first 50 pages of 'The Truth About Chernobyl' are devoted to excoriating the Chernobyl plant bureaucrats who overlooked safety problems, and ordered the ill-advised experiment that led to the reactor explosion.

These bureaucrats (Viktor Bryukhanov, Nikolai Fomin, and Anatoly Dyatlov) had little experience in the operation of nuclear power plants and were placed in positions of seniority mainly through political connection (which of course included membership in the Communist Party) rather than technical expertise.

Medvedev also has little respect for the Soviet bureaucracy that supervised the construction and operation of nuclear power plants across the country, many of which had secret histories of accidents and near-disasters, the result of design flaws in the reactors and shoddy construction.

The narrative then moves to a highly technical overview of the reactor's operation and the actions that led to the explosion; this is weakest part of the book, as Medvedev makes little effort to make his prose accessible to the layman. The presence of explanatory diagrams, charts, or schematics would have made reading this section much easier, but they are absent.

Where the book is strongest is in its chronological account of the actions taken after the explosion, on up to the second week in May, when Medvedev left the area to return to Moscow. These accounts provide insight into the confusion and disbelief, as well as the stupidity of many senior bureaucrats and officials, that exacerbated the severity of the situation.

One of the weaknesses of The Truth About Chernobyl is that it fails to cover the events after the first week of May, at which time Medvedev returned to Moscow.....thus, readers must consult other books for the epic tale of the thousands of 'liquidators' and construction personnel who cleaned up the area in the vicinity of the reactor and constructed the massive sarcophagous that entombs it to this day.

Summing up: while The Truth About Chernobyl lacks the insights of books written at a later time point post-disaster, when more information had become available, it remains one of the more important accounts of the accident and its immediate aftermath.

3 / 5 Stars

I remember when I first heard about the disaster at Chernobyl: it was on Tuesday, April 29, 1986. I was a graduate student at Louisiana State University at the time, and I was sitting in the barber shop in the Student Union, and a morning news program - I forget which one - was playing on the television mounted on the wall of the shop. The anchor announced that an accident had occurred at a nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union.

The coverage of the Chernobyl accident being broadcast on the televisions and newspapers in the United States was limited, and mainly comprised of rumor; this was back before there was an internet, or Twitter, or Facebook, and it was much easier for the Soviet government to hide the scope of the disaster. But it was quite obvious that something disastrous had happened in the Soviet Union, and as more details began to emerge over the following weeks, it became clear that the world's worst nuclear disaster had taken place.

On the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, I thought I would read one of the first books that addressed the phenomenon: Grigori Medvedev's The Truth About Chernobyl, which first was published in 1989 in Russia, followed by this English language translation (274 pp.; Basic Books) which was released in 1991.

The capsule summary: early in the morning of April 26, 1986, there was a catastrophic explosion of Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant at Pripyat, Ukraine (then a part of the Soviet Union). The accident led to the release of massive amounts of radioactive particulates (400 times more than that of the Hiroshima atomic bomb detonation) into the atmosphere, with fallout covering large areas of western and northern Europe.

The plant managers initially refused to believe that the reactor had been destroyed, and told the Soviet authorities in Moscow that the plant had suffered minor damage from a turbine explosion. It wasn't until the afternoon of April 27 that the authorities began the evacuation of the entire population (approximately 50,000 people) from Pripyat.

(an excellent photoessay on the disaster is available here)

Only the self-sacrificial actions of engineers and firefighters prevented the reactor from undergoing additional, even more disastrous, explosions. Using a labor force of a quarter of a million workers, by November 1986 a concrete 'sarcophagous' was erected over the ruins of the reactor. A massive effort to collect and bury radioactive debris and soil from the areas surrounding Pripyat continued into 1987. Ukrainian officials have declared that the area around Chenobyl will not be safe for human habitation for another 20,000 years.

Grigori Medvedev was a nuclear engineer who, in 1986, was working at the Soviet government's 'Suyuzatomenergostroy' national energy directorate. Medvedev had worked at a number of nuclear power plants in the USSR, including a stint as a deputy chief engineer at Chernobyl in the 1970s; he even had been hospitalized for radiation sickness (for an exposure that he does not detail). In May, 1986, he was sent by his management to Chernobyl to investigate the situation and report back. Much of the book's contents are derived from his observations and analysis associated with that investigation.

At the time the book was published in 1989, the Soviet government had refused to release to the public the complete truth of its investigations into the causes of the accident; this despite the emphasis on 'glasnost' by the Gorbachev presidency. So much of Medvedev's book is devoted - sometimes in an oblique way - to condemning the Soviet system, which in 1989 was a risky action even for a well-regarded engineer and subject matter expert like himself.

The first 50 pages of 'The Truth About Chernobyl' are devoted to excoriating the Chernobyl plant bureaucrats who overlooked safety problems, and ordered the ill-advised experiment that led to the reactor explosion.

These bureaucrats (Viktor Bryukhanov, Nikolai Fomin, and Anatoly Dyatlov) had little experience in the operation of nuclear power plants and were placed in positions of seniority mainly through political connection (which of course included membership in the Communist Party) rather than technical expertise.

Medvedev also has little respect for the Soviet bureaucracy that supervised the construction and operation of nuclear power plants across the country, many of which had secret histories of accidents and near-disasters, the result of design flaws in the reactors and shoddy construction.

The narrative then moves to a highly technical overview of the reactor's operation and the actions that led to the explosion; this is weakest part of the book, as Medvedev makes little effort to make his prose accessible to the layman. The presence of explanatory diagrams, charts, or schematics would have made reading this section much easier, but they are absent.

Where the book is strongest is in its chronological account of the actions taken after the explosion, on up to the second week in May, when Medvedev left the area to return to Moscow. These accounts provide insight into the confusion and disbelief, as well as the stupidity of many senior bureaucrats and officials, that exacerbated the severity of the situation.

Medvedev also presents a chapter on the fate of the workers and firemen who were transferred to Clinic No. 6 in Moscow for treatment of acute radiation exposure; the details of how many of these individuals succumbed are graphic and unsettling, and Medvedev uses these details to underscore the toll that the ineptitude and negligence of the Soviet system extracted from its citizens.

Summing up: while The Truth About Chernobyl lacks the insights of books written at a later time point post-disaster, when more information had become available, it remains one of the more important accounts of the accident and its immediate aftermath.