In the late 70s Harry Harrison authored several trade

paperback, sf art books : 'Great Balls of Fire' (1977), 'Mechanismo' (1978) and

'Planet Story' (1979). This was something of an adventure in sf publishing, for

at that time, art books with sf or fantasy themes were comparatively rare, and

the chain stores (Waldenbooks, Coles, and B. Dalton) that dominated the retail

sphere in those days were only just beginning to realize that additional shelf

space and inventory should be devoted to the genre.

Mechanismo (120 pp) is printed on quality stock, and at 10 ¼

x 10 ¼ “, couldn’t entirely fit onto the platen of my scanner. So the images I’m

posting here are cropped to some extent.

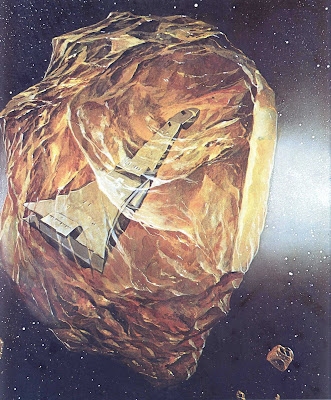

Angus McKie

Harrison’s contribution are 6 short essays on ‘Star Ships’, ‘Mechanical

Man’, Weapons and Space Gear’, ‘Space Cities’, ‘Fantastic Machines’, and ‘Movies’.

Additional text, apparently supplied by the publisher, provides commentary –

some of it fictional – for the illustrations. Most (all ?) of the artwork in

Mechanismo was previously published, usually as cover art for sf paperbacks

published in the UK.

Colin Hay

Jennifer Eachus

Richard Clifton-Dey

Overall,

Harrison’s essays are entertaining rather than pedantic, and written with a

note of humor. There are some tidbits dropped that may move readers to seek out

70s sf novels and story collections (for example, I’d never been aware of

Harrison’s matter transmission anthology, 'One Step from Earth' (1970), prior to

reading about it in Mechanismo).

Robin Hiddon

Jim Burns

Angus McKie

The quality of pieces (which are reproduced in black and

white and color) from the 19 participating artists varies; some are well done,

while others are mediocre. The works by Jim Burns, a rising star in the sf

illustration field, are among the most eye-catching. There are a large number

of contributions from Angus McKie, the leading sf illustrator in the late 70s

and a frequent contributor to Heavy Metal magazine. Ralph McQuarrie provides

some paintings from Star Wars, and there are a couple of H. R. Giger

submissions, too.

Angus McKie (cover of the March, 1979 issue of Heavy Metal)

‘Mechanismo’ may not draw much enthusiasm from contemporary

sf fans, who are used to the revolutionary changes in sf and fantasy

illustration wrought by the use of computers and illustration software. But

those with a nostalgic bent may want to pick up Mechanismo and take in the

flavor of Old School sf illustration.

Angus McKie

Ralph McQuarrie