Bester's 'The Stars My Destination' is one of the few 'Old School' SF classics that really lives up to its 'classic' status.

First published in 1956, the novel borrows its plot from 'The Count of Monte Cristo' :

In the aftermath of an unprovoked attack on the spaceship Nomad, crewman Gully Foyle survives among the floating ruins of his vessel by outfitting a storage locker as an emergency survival compartment. Foyle, clad in his spacesuit, desperately scavenges oxygen canisters and tins of food and water from the wreckage, hoping to survive long enough to be rescued.

Foyle is in his 171st day aboard the Nomad, when he espies an approaching vessel. Rescue is within his reach...or so it seems....

In the aftermath of an unprovoked attack on the spaceship Nomad, crewman Gully Foyle survives among the floating ruins of his vessel by outfitting a storage locker as an emergency survival compartment. Foyle, clad in his spacesuit, desperately scavenges oxygen canisters and tins of food and water from the wreckage, hoping to survive long enough to be rescued.

Foyle is in his 171st day aboard the Nomad, when he espies an approaching vessel. Rescue is within his reach...or so it seems....

'Stars' has a very 'modern' approach to its prose style, plotting, and characterization, which made it stand out from the wooden material being churned out in the late 50s by Arthur Clarke, James Blish, and Isaac Asimov (among others).

Throughout the 70s, editor and author Byron Preiss (1953 - 2005) was active in publishing illustrated editions of sf mass-market and trade paperbacks. One of his ventures involved a small New York City publisher named Baronet, who in the late 70s released 'The Illustrated Harlan Ellison' and 'The Illustrated Roger Zelazny', as well as the illustrated 'The Stars My Destination'.

The publication history of 'Stars' is complicated. In July 1979 Baronet released 'The Stars My Destination, Volume One: The Graphic Story Adaptation' as a trade paperback and as a deluxe-edition hardcover in a slipcase, with an empty slot preserved as a space for the planned volume 2.

Excerpts of Volume One and Volume Two were published in Heavy Metal magazine; the November 1979 issue featured the first chapter of Volume Two, which I've posted below.

Excerpts of Volume One and Volume Two were published in Heavy Metal magazine; the November 1979 issue featured the first chapter of Volume Two, which I've posted below.

Unfortunately, Baronet went out of business soon after releasing Volume One, and the draft of Volume Two sat in a warehouse in Queens, New York, for 12 years until Carl Potts, editor of Marvel's 'Epic Illustrated' magazine, expressed an interest in publishing a complete edition of the book.

After further labors by Preiss, the Complete Alfred Bester's The Stars My Destination' was released in 1992 by Epic.

After further labors by Preiss, the Complete Alfred Bester's The Stars My Destination' was released in 1992 by Epic.

Readers interested in picking up a copy can find it at amazon.com and eBay for affordable prices, but take care that you purchase the 'Complete' version, as opposed to Volume One (which shares the same cover).

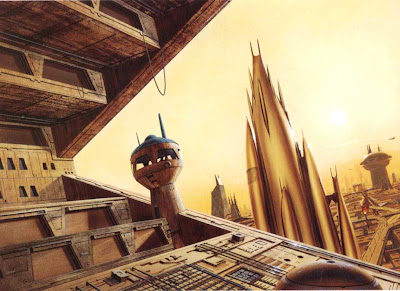

If you've never read Bester's novel, the Chaykin / Preiss edition is probably the best way to take it in. While the graphic story is abridged, the quantity of excised text is very minor, and the full flavor of the novel is well retained.

Chaykin's illustrations are an able interpretation of the visual images described in the text. Their variety and quantity are impressive, particularly in light of the fact that they were done in the era prior to the advent of computer - assisted graphics.

.jpg)