Book Review: 'Armed Camps' by Kit Reed

1 / 5 Stars

By the late 1960s America’s Intellectual Class, a group of people who are nowadays called ‘The Liberal Elite’, faced a dilemma regarding the increasing rise of violent behavior in society.

Some members of the elite embraced violence as an evil necessary for the Liberation of the Oppressed, and reveled (at a careful distance) in it under the guise of ‘Radical Chic’. This so-chic attitude toward violent revolution reached its bizarre apex in the case of Jewish American Princess Bernardine (Ohrnstein) Dohrn, who, with her husband (Friend of Barack) Bill Ayers, started the Revolutionary Youth Movement and later, the Weather Underground.

Other members of the elite believed that, while the tumult of the era had its justifiable roots in social and political oppression, the mass media had exploited violence for its own sake, and directly aided and abetted the release of something dangerous from the American psyche.

These liberals believed that unless the depiction of violence in the media and entertainment venues was ‘subdued’ by federal intervention (no liberal dared explicitly mention ‘censored’) the rate of rapes, murders, muggings, and other anti-social behaviors would continue to increase.

Kit Reed (the pseudonym of Lillian Craig Reed) was a New Wave-era SF author, still publishing today, who focused (as many New Wave writers did) on social issues, as opposed to traditional ‘hard’ SF.

Her short novel ‘Armed Camps’ (1969) extrapolates a fictional, near-future USA that has been generated by the new forms of violence spawned in the 60s.

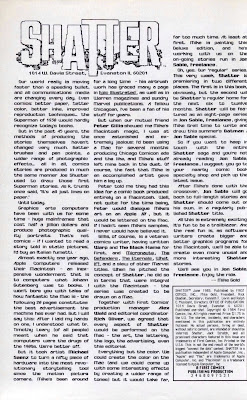

Originally published in 1969, this Berkley paperback (158 pp.) edition was issued in November 1971; the cover artist is Richard Powers.

‘Camps’, which is set in the 1990s (or later), posits an America in which the nation is little more than a police state racked by anarchy and decay. The war in Vietnam has expanded into a global contest, and orbiting missiles threaten an instant Armageddon should tempers get out of hand. While the ruling class is sheltered to some extent from political and social violence, many young people have adopted a fatalistic approach to life, focusing on losing themselves in hedonism.

The story alternates between two first-person narrators: one is Danny March, a soldier who participates in staged, arena-like combats against troops from opposing nations; flamethrowers are wielded by all contestants. This approach to settling international disputes presumably prevents nuclear war from breaking out. For reasons that are not disclosed until the last few pages of the novel, Danny has violated his term of service in the Army, and he is condemned to live chained to a pole on the grounds of a military base, filmed by television cameras, a constant reminder of the punishment dealt those who provoke the reigning order.

The other narrator is a young woman named Anne; as the novel opens she is suffering from severe emotional trauma from some undisclosed event. Anne finds refuge in Cambria, a rural commune devoted to life paced by peace, love, and understanding; its leader is a charismatic young man named Eamon.

As an anti-war, anti-violence novel, ‘Camps’ has a predictably downbeat tenor, and while there is nothing inherently wrong with this, author Reed doesn’t do much with her literary construction. The storylines of these two characters unfold in the form of overly lengthy monologues, often consisting of run-on sentences unmarred by the use of periods, a common affectation of New Wave artistes.

The Danny March portion of the book is the weakest; Reed’s approach to framing his monologues are clearly derived from Dalton Trumbo’s novel ‘Johnny Got His Gun’ (the antiwar novel of the 60s, although it was actually written in 1938). The introduction of a schizophrenic note to March’s inner musings is contrived, serving mainly to pad the narrative rather than imparting much in the way of momentum.

The alternate plot involving Anne and the fate of Cambria is a bit more engrossing; it does offer a more rewarding denouement, as well as providing a more original treatment of the ways in which good intentions collide with the reality of human nature.

Overall, I found ‘Camps’ to be too much of a slog to be very rewarding. Readers with a fondness for an antiwar novel with a quasi-SF component may find ‘Camps’ worthwhile, but everyone else is better passing on this book.