'Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files 02'

Rebellion / 2000 AD, December 2010

Judge Dredd was created in 1976 by the English comics writer John Wagner, in response to a request from fellow freelancer Pat Mills. Mills was developing a science fiction comic book for UK publisher IPC. Spanish artist Carlos Ezquerra was responsible for crafting the visual design of the character, who was a lawman in a chaotic, near-future New York City.

Judge Dredd debuted in issue 2 (‘Prog 2’) of 2000 AD in March 1977 in a story titled ‘Judge Whitey’. Unlike the American import comics from DC and Marvel, which dominated a big segment of the UK market at the time, 2000 AD was an anthology issued on a weekly basis, with color covers and black and white interiors. Judge Dredd quickly became one of the more popular features in 2000 AD.

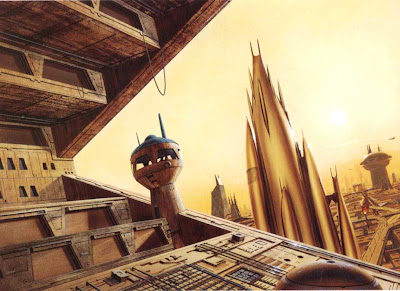

The Dredd adventures are set in the USA of 2099; most of the interior of the continent is a wasteland, the result of a series of nuclear and biochemical wars. Its inhabitants are mutants and outcasts. Judge Dredd is charged with maintaining law and order in the east coast megalopolis of Mega-City One (formerly New York City), Mega-City Two representing the west coast and the former L.A. The 400 million denizens of Mega-City One are crammed into enormous high-rise apartment complexes, while the undercity far below is a world of garbage, fetid darkness, and a prime hideout for criminals.

Starting in 2010, publisher Rebellion is releasing black and white, paperbound compilations of the early 2000 AD comics, including the Judge Dredd comics, in the format similar to that employed by DC with its ‘Showcase’ books, and Marvel with its ‘Marvel Essentials’ books.

Judge Dredd debuted in issue 2 (‘Prog 2’) of 2000 AD in March 1977 in a story titled ‘Judge Whitey’. Unlike the American import comics from DC and Marvel, which dominated a big segment of the UK market at the time, 2000 AD was an anthology issued on a weekly basis, with color covers and black and white interiors. Judge Dredd quickly became one of the more popular features in 2000 AD.

The Dredd adventures are set in the USA of 2099; most of the interior of the continent is a wasteland, the result of a series of nuclear and biochemical wars. Its inhabitants are mutants and outcasts. Judge Dredd is charged with maintaining law and order in the east coast megalopolis of Mega-City One (formerly New York City), Mega-City Two representing the west coast and the former L.A. The 400 million denizens of Mega-City One are crammed into enormous high-rise apartment complexes, while the undercity far below is a world of garbage, fetid darkness, and a prime hideout for criminals.

Starting in 2010, publisher Rebellion is releasing black and white, paperbound compilations of the early 2000 AD comics, including the Judge Dredd comics, in the format similar to that employed by DC with its ‘Showcase’ books, and Marvel with its ‘Marvel Essentials’ books.

As of February 2012, four volumes in the Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files’ series have been issued. Volume 1 is perhaps the weakest, as the stories it contains are mainly 8 pages-or-fewer, one-shot episodes.

Volume 2 features the two major story arcs for the ’78 and ’79 appearances of Judge Dredd.

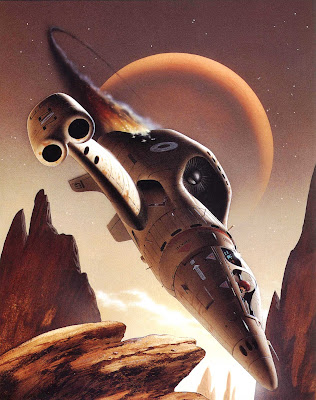

‘The Cursed Earth’ (May – October 1978) sees Dredd, an alien named ‘Tweak’, and (British) punk ‘Spikes Harvey Rotten’ on a suicidal mission to cross the blasted interior of the USA in order to deliver a vaccine to a plague-ravaged Mega-City Two.

[Sadly, some episodes that appeared in the 2000 AD strips are deleted in this Rebellion reprint, following successful copyright infringement suits against IPC by General Mills (over a satirical depiction of ‘The Jolly Green Giant’), and McDonalds and Burger King (over the ‘Burger Wars’ episodes). As well, a satirical depiction of KFC’s Colonel Sanders (the 'Dr Gribbon' character in the ‘Soul Food’ episodes) also drew a complaint.]

The second major arc in ‘Case Files 02’ involves ‘Judge Cal’ (i.e., Caligula), and ran from October 1978 to April 1979. Here, Dredd finds himself a hunted outcast when the corrupt and decadent Cal takes over Mega-City One.

‘Case Files 02’ closes with some shorter episodes: ‘Punks Rule’, ‘The Exo-Men’, and ‘The DNA-Man’.

The artwork for these Dredd comics varies from the loose, if energetic style of Mike McMahon, to the fine draftsmanship of Brian Boland, Brett Ewins, and Ron Smith, which reproduces very well here.

Compared to American comics of the late 70s, the Dredd tales were a fresh take, filled with violent action (there was no Comics Code hampering the UK industry), and plenty of irreverent, satirical humor, in marked contrast to the sententious, labored, and overwrought nature of many of the Marvel and DC titles of the same era.

Fans of comic books from the 70s, as well as fans of the unique way in which the British interpret the landscape of American popular culture, will want to take a look at the 'Judge Dredd Case Files' compilations.