5 / 5 Stars

‘Damnation Alley’ first appeared in 1967 in Galaxy digest as a novella; Zelazny later expanded it into a novel for publication in 1969. This Berkley Books paperback (157 pp), with a cover illustration by Paul Lehr, was released in June, 1970.

I remember reading the novel back when it first came out and finding it something of a novelty…..and a welcome novelty, at that. For in 1970 the New Wave movement was well emplaced in sf, and straightforward adventure novels like ‘Damnation Alley’ were rare.

The novel was of course made into a 1977 movie which is not regarded as one of the finest moments in sf cinema. But 47 years after it was first published, the novel still is engaging and readable.

The plot is straightforward: 100 years or so following World War Three, most of the interior of the USA is a wasteland populated by mutated animals – including gila monsters the size of small trucks. Zones of radiation left from nuke detonations mean certain death for those who lack the necessary shielding. The atmosphere has been altered, and storms of lethal ferocity regularly scour the landscapes, rendering air travel impossible.

An outbreak of bubonic plague in Boston threatens to depopulate the entire city; the only hope of succor is the depots of ‘Haffikine antiserum’ in the possession of Los Angeles. An ex-Hells Angel and ex-felon, with the appropriate name of Hell Tanner, is offered a deal: a Pardon for all of his offences, provided he delivers the antiserum to Boston – by driving across the country on the route known as Damnation Alley.

No one ever has made the complete Alley drive and survived. But Tanner is equipped with the latest in technology: a Super Car with eight all-terrain wheels, automated viewscreens, and a pleasing arsenal of rockets, machine guns, and flamethrowers.

Hell Tanner sets out on the Alley run…….but in case he decides to change his mind and break for freedom rather than Boston, two other cars are travelling right behind him……….with orders to kill Tanner the moment he tries to deviate from his mission…..

Although Zelazny may have considered ‘Damnation Alley’ as a less ‘artistic’ novel than his other works of the time, looking back on it from nearly 50 years later, it arguably broke new ground in the adventure novel genre. Its use of an antihero represents a break from the standard sf traditions of the time. The setting of a diseased and blasted landscape, filled with perpetual dangers, remains imaginative.

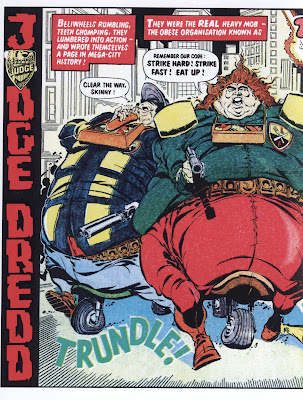

Zelazny’s openly cynical approach to the aftermath of the Apocalypse, one that refuses to adopt the standard humanistic approach of self-salvation arising from the ashes, was influential in sci-fi culture. For example, in 1978, 2000 AD magazine ran a lengthy Judge Dredd story, 'The Cursed Earth', that was heavily influenced by 'Damnation', although it worked in passages of mordant humor that quite were lacking in Zelazny's novel.

That’s not to say that ‘Damnation’ is a perfect novel. Zelazny couldn’t quite resist the urge to insert several New Wave prose segments into his novel. These take the form of prose poems, some of which are two pages on length, and are barely coherent. I can’t imagine any modern-day readers responding well to these affectations.

Still, when all is said and done, in my opinion, ‘Damnation Alley’ remains one of the best sf novels to be published in the 1960s, and, along with Jack of Shadows, one of Zelazny’s better works.

That’s not to say that ‘Damnation’ is a perfect novel. Zelazny couldn’t quite resist the urge to insert several New Wave prose segments into his novel. These take the form of prose poems, some of which are two pages on length, and are barely coherent. I can’t imagine any modern-day readers responding well to these affectations.

Still, when all is said and done, in my opinion, ‘Damnation Alley’ remains one of the best sf novels to be published in the 1960s, and, along with Jack of Shadows, one of Zelazny’s better works.

.jpg)