Book Review: 'Blue Face' by G. C. Edmondson

4 / 5 Stars

‘Blue Face’ first was published in 1971 in hardcover by Doubleday, with the title ‘Chapayeca’. This DAW paperback (128 pp.) was issued in 1971 and features a cover illustration by Karel Thole.

Thanks to the best-selling books by Carlos Castaneda, by 1971 the Yaqui Indians of Mexico’s Sonoran desert were the Indigenous Tribe Most Beloved by White People. It was not unusual for hippies and wanna-be mystics to travel to Yaqui country hoping to meet, if not the superstar Don Juan Matus himself, then another brujo or shaman who could usher them into the sacred mysteries of the Yaqui experience.

One Yaqui religious ceremony that a tourist might witness was the Easter celebration, in which male members of the tribe would don masks crafted to represent a chapayeca (‘long nose’), an evil follower of Judas Iscariot. So how do the chapayecas figure into this SF novel ?

Things are not going well for anthropologist Nash Taber. The federal authorities want to talk to him about sheltering Yaqui Indians who are in the US illegally. He is in constant pain and popping pills from a back injury suffered in a car accident. He has diabetes. And his job as a university faculty member is looking less and less secure.

In a desperate effort to uncover the rumored last redoubt of the Yaqui and salvage his career, Taber travels to Mexico for a rendezvous with Lico, one of his Yaqui friends. After some adventures they do indeed arrive at the last holdout of the Indians, where Taber observes a chapayeca wearing a most unusual piece of blue plastic clothing. It turns out that ‘Chap’ is in fact an alien; his face, however much it may resemble a ceremonial mask, is real.

Once he recovers from his astonishment, Taber starts to scheme. If he can get this rather naïve alien away from the Yaqui and into the US, then there are all sorts of financial windfalls that could come his way. But maneuvering a way to bring Chap out of the desert isn’t going to be easy.

For one thing, the truculent younger men of the village have their own plans for the alien, and they aren’t going to let a gimpy gringo interfere with those plans. And the Mexican police are actively hunting for Taber, suspecting him of being a would-be revolutionary for the Yaqui cause. It’s going to take some very careful cross-cultural exchanges in order for Taber to get out of Mexico alive…

‘Blue Face’ is an interesting little book and represents one of the more engaging of the short novels that DAW books regularly issued to fill out its catalogue during the first few years of its operation. Author Edmondson employs a very spare, unadorned prose style that relies heavily on dialogue; but he is skillful at this aspect of his craft, and as a consequence the narrative flows along at a fast clip. The story is difficult to categorize, but is perhaps best labeled as a quirky mix of wry humor, interesting insights into Yaqui society, and brief episodes of violence and mayhem.

'Blue Face' is well worth searching out.

Friday, October 1, 2010

Monday, September 27, 2010

Book Review: The Panorama Egg

Book Review: 'The Panorama Egg' by A. E. Silas

3 / 5 Stars

As best as I can tell, ‘The Panorama Egg’ is the sole book published by A(nne) E. Silas (information on the author’s exact identity is not available on the web). ‘Egg’ (224 pp.) is DAW book No. 302 and appeared in August 1978; the cover illustration is by H. R. Van Dongen.

The panorama egg of the book’s title refers to an egg- usually of synthetic construction- that has been hollowed out and a landscape carefully painted on the interior of the shell. A small aperture is made in the end of the egg through which one can look in and admire the artwork.

Hal Archer is unhappy with his life. He is in his early 30s and out of shape; his wife has left him for another man; and while he is on track to become a full partner in the law firm where he works, he feels unsatisfied and adrift. His one real pastime involves collecting panorama eggs. The one egg he yearns to find is a unique egg where the interior scenery is not static but in fact the image of living world, perhaps a world located in another dimension.

On a cozy evening at the home of his actor friend Henry Patterson, Archer meets an enigmatic little woman named Mera Melaklos; in due course Melaklos offers Archer the panorama egg he has been seeking. Gazing into the egg’s interior, Archer espies a grassy sward, trees, blue skies, and tufts of clouds. When Melaklos invites him to journey to the world encapsulated within the egg, Archer agrees. And instantly he is transported to the land known as Dolesar.

Once in Dolesar, Archer embarks on a series of adventures engineered by the mysterious Melaklos. It seems that there is strife growing among the medieval towns and cities and rural areas of Dolesar; there are rumors of depredations committed by ‘tiger men’, who are enthralled by the sorcery of a Dark Lord. Archer gradually comes to realize that he is far from a tourist in the strange world contained in the panorama egg; indeed, he may be the linchpin of a last, desperate plan to combat the nefarious designs of the Dark Lord. But Archer is no wizard, and in a land where magic works, that can be a major hazard to one’s liberty and life….

In some ways ‘Egg’ approaches the genre much like the Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever series by Stephen R. Donaldson, which also appeared in the late 70s, and featured a contemporary protagonist adrift in a strange landscape. However, Silas’s Archer, while not the most adept of sword wielders, is refreshingly devoid of the relentless angst that belabored every nuance of the Covenant character.

As a first-time novel, ‘Egg’ has its strengths and weaknesses. The novel starts with an interesting premise and an offbeat approach to inserting a modern man into a fantasy world peopled by giants, dwarves, cat people, and sea serpents. However, Dolesar itself is a rather generic fantasy setting, and the narrative loses quite a bit of momentum once the action moves to that locale. It’s not until well into the midway portion of the book that the Deep Secrets and Conspiracies hinted at throughout the initial chapters gradually are disclosed, and Archer takes a more active role in his defense of the realm.

‘The Panorama Egg’ might best be enjoyed by readers looking for a more low-key fantasy adventure, one featuring a small cast of characters, and an emphasis on the dialogue-mediated psychological and emotional interactions among these characters. Readers seeking a novel with the larger-than-life sweep and scope of epic fantasy won't find it in this story.

3 / 5 Stars

As best as I can tell, ‘The Panorama Egg’ is the sole book published by A(nne) E. Silas (information on the author’s exact identity is not available on the web). ‘Egg’ (224 pp.) is DAW book No. 302 and appeared in August 1978; the cover illustration is by H. R. Van Dongen.

The panorama egg of the book’s title refers to an egg- usually of synthetic construction- that has been hollowed out and a landscape carefully painted on the interior of the shell. A small aperture is made in the end of the egg through which one can look in and admire the artwork.

Hal Archer is unhappy with his life. He is in his early 30s and out of shape; his wife has left him for another man; and while he is on track to become a full partner in the law firm where he works, he feels unsatisfied and adrift. His one real pastime involves collecting panorama eggs. The one egg he yearns to find is a unique egg where the interior scenery is not static but in fact the image of living world, perhaps a world located in another dimension.

On a cozy evening at the home of his actor friend Henry Patterson, Archer meets an enigmatic little woman named Mera Melaklos; in due course Melaklos offers Archer the panorama egg he has been seeking. Gazing into the egg’s interior, Archer espies a grassy sward, trees, blue skies, and tufts of clouds. When Melaklos invites him to journey to the world encapsulated within the egg, Archer agrees. And instantly he is transported to the land known as Dolesar.

Once in Dolesar, Archer embarks on a series of adventures engineered by the mysterious Melaklos. It seems that there is strife growing among the medieval towns and cities and rural areas of Dolesar; there are rumors of depredations committed by ‘tiger men’, who are enthralled by the sorcery of a Dark Lord. Archer gradually comes to realize that he is far from a tourist in the strange world contained in the panorama egg; indeed, he may be the linchpin of a last, desperate plan to combat the nefarious designs of the Dark Lord. But Archer is no wizard, and in a land where magic works, that can be a major hazard to one’s liberty and life….

In some ways ‘Egg’ approaches the genre much like the Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever series by Stephen R. Donaldson, which also appeared in the late 70s, and featured a contemporary protagonist adrift in a strange landscape. However, Silas’s Archer, while not the most adept of sword wielders, is refreshingly devoid of the relentless angst that belabored every nuance of the Covenant character.

As a first-time novel, ‘Egg’ has its strengths and weaknesses. The novel starts with an interesting premise and an offbeat approach to inserting a modern man into a fantasy world peopled by giants, dwarves, cat people, and sea serpents. However, Dolesar itself is a rather generic fantasy setting, and the narrative loses quite a bit of momentum once the action moves to that locale. It’s not until well into the midway portion of the book that the Deep Secrets and Conspiracies hinted at throughout the initial chapters gradually are disclosed, and Archer takes a more active role in his defense of the realm.

‘The Panorama Egg’ might best be enjoyed by readers looking for a more low-key fantasy adventure, one featuring a small cast of characters, and an emphasis on the dialogue-mediated psychological and emotional interactions among these characters. Readers seeking a novel with the larger-than-life sweep and scope of epic fantasy won't find it in this story.

Labels:

The Panorama Egg

Saturday, September 25, 2010

The Beinart International Surreal Art Collective

A very interesting website devoted to bizarre realism, surrealism, and fantastic art.

Labels:

Beinart Collective

Thursday, September 23, 2010

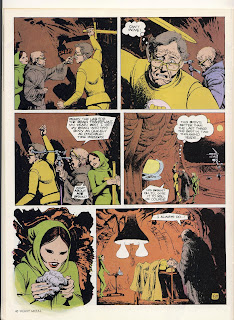

'Into the Breach' by John Shirley (story) and Leo Duranona (art)

from the September 1980 issue of Heavy Metal

from the September 1980 issue of Heavy Metal

Labels:

The Breach

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Book Review: Flashing Swords #2

Book Review: 'Flashing Swords ! # 2' edited by Lin Carter

2 / 5 Stars

‘Flashing Swords ! # 2’ (268 pp.) was edited by Lin Carter and published by Dell in 1974; the cover illustration is by Frank Frazetta.

The 'Flashing Swords' series was designed to showcase all-new short stories and novelettes of heroic fantasy, authored by prominent practitioners of the genre - who happened to be held in high regard by editor Carter, of course.

The anthology opens with ‘The Rug and the Bull’ by L. Sprague de Camp; set in Camp’s ‘Pusad’ universe of ancient Atlantis, it deals with the amiable mage Gezun and his plans to earn a living by marketing magic carpets. The narrative’s tone is light and humorous; however, de Camp’s contrived and cutesy dialogue (be prepared to encounter ‘methinks’, ‘forsooth’ and ‘ensorcellment’, among other terms) lays on too much treacle.

Michael Moorcock contributes an Elric tale, ‘The Jade Man’s Eyes’. Elric and Moonglum accompany the adventurer Duke Avan to the lost city of R’lin K’ren A’a, where treasure awaits, and perhaps clues to the origin of the Menibonean race. With a downbeat atmosphere and ending, this is one of the better of the early Elric stories.

Andre Norton contributes a lengthy ‘Witchworld’ story, ‘Toads of Grimmerdale’. Hertha, a young woman made outcast from her village of Trewsdale, seeks revenge on the soldier of fortune who assaulted her. She enters into a bargain with the otherworldly creatures who lurk at the circle of stones in Grimmerdale; but like many bargains with the Dark Side of the Force, this one, too, has its catch…. I found this story to be a bit too deliberate and slow-paced for my liking, but fans of Norton’s fiction may find it appealing.

John Jakes provides a 'Brak the Barbarian' tale with ‘Ghoul’s Garden’. While traveling through a lonely wood, Brak rescues an actress and a querulous priest from certain death. As the trio resumes their journey it becomes clear that the actress has a troubling secret. Atmospheric, and featuring a creepy villain and unusual magic, this is one of the better Brak tales.

All in all, ‘Flashing Swords ! #2’ is not the most memorable of these anthologies. I came away from reading it with the feeling that, once the mid-70s had been reached, more than a few of the writers in Lin Carter’s circle were rather played out creatively. When it came time to contribute something to his story collections, their submissions were workmanlike, but not all that inspiring.

Unless you are determined to collect every volume in the ‘Flashing Swords !’ series, this one can be passed over.

‘Flashing Swords ! # 2’ (268 pp.) was edited by Lin Carter and published by Dell in 1974; the cover illustration is by Frank Frazetta.

The 'Flashing Swords' series was designed to showcase all-new short stories and novelettes of heroic fantasy, authored by prominent practitioners of the genre - who happened to be held in high regard by editor Carter, of course.

The anthology opens with ‘The Rug and the Bull’ by L. Sprague de Camp; set in Camp’s ‘Pusad’ universe of ancient Atlantis, it deals with the amiable mage Gezun and his plans to earn a living by marketing magic carpets. The narrative’s tone is light and humorous; however, de Camp’s contrived and cutesy dialogue (be prepared to encounter ‘methinks’, ‘forsooth’ and ‘ensorcellment’, among other terms) lays on too much treacle.

Michael Moorcock contributes an Elric tale, ‘The Jade Man’s Eyes’. Elric and Moonglum accompany the adventurer Duke Avan to the lost city of R’lin K’ren A’a, where treasure awaits, and perhaps clues to the origin of the Menibonean race. With a downbeat atmosphere and ending, this is one of the better of the early Elric stories.

Andre Norton contributes a lengthy ‘Witchworld’ story, ‘Toads of Grimmerdale’. Hertha, a young woman made outcast from her village of Trewsdale, seeks revenge on the soldier of fortune who assaulted her. She enters into a bargain with the otherworldly creatures who lurk at the circle of stones in Grimmerdale; but like many bargains with the Dark Side of the Force, this one, too, has its catch…. I found this story to be a bit too deliberate and slow-paced for my liking, but fans of Norton’s fiction may find it appealing.

John Jakes provides a 'Brak the Barbarian' tale with ‘Ghoul’s Garden’. While traveling through a lonely wood, Brak rescues an actress and a querulous priest from certain death. As the trio resumes their journey it becomes clear that the actress has a troubling secret. Atmospheric, and featuring a creepy villain and unusual magic, this is one of the better Brak tales.

All in all, ‘Flashing Swords ! #2’ is not the most memorable of these anthologies. I came away from reading it with the feeling that, once the mid-70s had been reached, more than a few of the writers in Lin Carter’s circle were rather played out creatively. When it came time to contribute something to his story collections, their submissions were workmanlike, but not all that inspiring.

Unless you are determined to collect every volume in the ‘Flashing Swords !’ series, this one can be passed over.

Labels:

Flashing Swords 2

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

Labels:

The essence of Heavy Metal

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Book Review: Nebula Award Stories

Book Review: 'Nebula Award Stories', edited by Damon Knight

2 / 5 Stars

2 / 5 Stars

If the New Wave movement in the US could be said to have a starting point it was probably 1965, the year that saw the release of determinedly untraditional stories like Harlan Ellison’s ”Repent, Harlequin ! Said the Ticktockman”, and Roger Zelazny’s ‘The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth’.

Needless to say, Damon Knight and other members of the newly formed SFWA were set on promoting New Wave works as part of their effort to get SF recognized by mainstream authors and publishing houses as genuine ‘Literature’. Along with this tactic, Knight and Co. advanced the idea that authors such as Kurt Vonnegut, Donald Barthelme, and Thomas Pynchon (held in godlike esteem by New Wave SF writers) were writing ‘speculative fiction’.

Accordingly, science fiction authors who imitated the prose styles of Pynchon also could be regarded as legitimate purveyors of speculative fiction, and due the requisite accolades apportioned to those who bravely sought a way out of the otherwise juvenile ghetto of genre SF.

So it was that the inaugural Nebula Awards for 1965 emphasized New Wave tales, and the winners, along with some nominees, are collected here in the pages of 'Nebula Award Stories' (Pocket Books, November 1967, 244 pp., cover artist uncredited).

My capsule summaries of the contents:

‘The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth’: a quintessential New Wave story. The plot, which deals with a divorced couple’s uneasy participation on a fishing expedition on the seas of Venus, is pretty much an afterthought. Instead, Zelazny places all his emphasis on writing arty dialogue, as well as interjecting sequences of figurative prose designed to showcase the psychological landscape inhabited by his main character.

James H. Schmitz provides ‘Balanced Ecology’, which is considerably more conventional in terms of plotting and prose style. On a planet that features the only stands in the Universe of ‘diamondwood’ trees, two children must confront a sinister plot to deprive them of their inheritance. This is one of the better tales in the collection.

Ellison’s ‘Ticktockman’ comes next. While it possessed considerable cachet at the time of its release, it has aged poorly and with the passage of time it has come to seem overly contrived, even cutesy.

Zelazny returns with a novelette, ‘He Who Shapes’, about a psychiatrist who uses a high-tech gadget to insert himself into the thoughts and dreams of his patients. Zelazny’s prose is a bit more restrained here, although some purple-worded passages do intrude every now and then. One thing I noticed about ‘Shapes’ was how prominently cigarette smoking figures into the everyday activities of the characters (although the story was written in 1965, after all, when smoking was widespread). It’s amazing none of the characters succumb to lung cancer before the novelette's final sentence..........

Gordon Dickson’s entry, ‘Computers Don’t Argue’ is a mordant tale of a hapless book club subscriber who runs afoul of a computerized mailing system. While contemporary readers may raise an eyebrow over the use of the term ‘punch cards’, the underlying theme of the story remains relevant.

Larry Niven’s ‘Becalmed in Hell’ deals with the first spaceship to land on Venus; the brain-in-a-jar autopilot suffers a malfunction and loses the ability to pilot the ship. The sole human member of the crew must figure out how to solve the malfunction if he hopes to survive.

Brian Aldiss’s ‘The Saliva Tree’ features a space alien loose in rural England at the end of the 19th century. In many ways it can be labeled a proto-Steampunk tale, with some elements of Lovecraft’s ‘The Color Out of Space’ tossed in. Featuring a very accessible prose style, ‘Tree’ indicated that, when he was not infatuated with trying to emulate J. G. Ballard, Aldiss could produce an engaging story. Modern-day readers will find ‘Tree’ to be one of the more appealing entries in this collection.

Mr. New Wave himself, J. G. Ballard, is represented by ‘The Drowned Giant’, which in my opinion deserved the 1965 short story Nebula Award more so than Ellison’s ‘Ticktockman’.

‘Giant’ imparts a melancholy, existential quality to its tale of a giant corpse washed ashore and picked over by the inhabitants of an English coastal town. Even after the passage of 45 years, it remains one of the best representatives of the New Wave approach to storytelling.

To sum up, ‘Nebula Award Stories’ offers three or four good stories within its pages, not enough to mark it as a must-have. But for those with an interest in the early years of the New Wave movement, it may be worth searching out.

Labels:

Nebula Award Stories

Book Review: Garbage World

Book Review: 'Garbage World' by Charles Platt

2 / 5 Stars

2 / 5 Stars

‘Garbage World’ was published in 1967 (Belmont Tower Books paperback edition,144 pp.; cover artist is uncredited).

In a colonized asteroid belt, garbage is loaded into large ‘blimps’ and jetted across space to crash-land on the asteroid Kopra, the designated trash heap for the system. After decades of serving as a landfill, the rocky surface of Kopra is buried under a layer of waste 10 miles thick. The scattered villages that lie atop this strata of garbage are happy enough with their lot, picking through each blimp’s contents for salvageable items, drinking moonshine, and partying when the occasion demands it. The Koprans are hostile towards the colonists of the other asteroids, seeing them as supercilious weenies with an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality.

As the novel opens, a survey ship from the asteroid belt government lands on Kopra. Its two passengers, a bureaucrat named Larkin and his assistant, Oliver Roach, have bad news for the Koprans: the layer of trash surrounding the asteroid has grown so large as to make the asteroid’s orbit unstable. In order to prevent the trash from flying off the surface and into the orbits of the other asteroids, the gravity generator on Kopra will have to be replaced. And for that to take place, everyone on Kopra will have to be evacuated. This news is met with anger by the inhabitants of the garbage world. It’s up to Oliver Roach to gain their confidence and effect their removal.

‘Garbage World’ is a serviceable, but not particularly exciting, SF adventure. It’s not really a New Wave SF tale, but it does display the expanded approach to the genre that typified the New Wave ethos. By focusing on the sociology of the Kopran civilization and its uneasy relationship with the affluent worlds that enable it to survive in its own (rather deviant) manner, Platt was effectively prefiguring the ‘Garbage Mountain’ reality of Third World life in the present day.

Take, for example, the Payatas dump in the suburbs of Manilla:

As we come over a rise, my first glimpse of Payatas is hallucinatory: a great smoky-gray mass that towers above the trees and shanties creeping up to its edge. On the rounded summit, almost the same color as the thunderheads that mass over the city in the afternoons, a tiny backhoe crawls along a contour, seeming to float in the sky. As we approach, shapes and colors emerge out of the gray. What at first seemed to be flocks of seagulls spiraling upward in a hot wind reveal themselves to be cyclones of plastic bags. The huge hill itself appears to shimmer in the heat, and then its surface resolves into a moving mass of people, hundreds of them, scuttling like termites over a mound. From this distance, with the wind blowing the other way, Payatas displays a terrible beauty, inspiring an amoral wonder at the sheer scale and collective will that built it, over many years, from the accumulated detritus of millions of lives.

Hundreds of scavengers, brandishing kalahigs and sacks, faces covered with filthy T-shirts, eyes peering out like desert nomads' through the neck holes, gather in clutches across the dump. Gulls and stray dogs with heavy udders prowl the margins, but the summit is a solely human domain. The impression is of pure entropy, a mass of people as disordered as the refuse itself, swarming frantically over the surface. But patterns emerge, and as trucks dump each new load with a shriek of gears and a sickening glorp of wet garbage, the scavengers surge forward, tearing open plastic bags, spearing cans and plastic bottles with a choreographed efficiency.

In this regard, ‘Garbage World’ may be seen as an example of the ways in which SF can address topics and issues well in advance of other genres of literature.

In a colonized asteroid belt, garbage is loaded into large ‘blimps’ and jetted across space to crash-land on the asteroid Kopra, the designated trash heap for the system. After decades of serving as a landfill, the rocky surface of Kopra is buried under a layer of waste 10 miles thick. The scattered villages that lie atop this strata of garbage are happy enough with their lot, picking through each blimp’s contents for salvageable items, drinking moonshine, and partying when the occasion demands it. The Koprans are hostile towards the colonists of the other asteroids, seeing them as supercilious weenies with an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality.

As the novel opens, a survey ship from the asteroid belt government lands on Kopra. Its two passengers, a bureaucrat named Larkin and his assistant, Oliver Roach, have bad news for the Koprans: the layer of trash surrounding the asteroid has grown so large as to make the asteroid’s orbit unstable. In order to prevent the trash from flying off the surface and into the orbits of the other asteroids, the gravity generator on Kopra will have to be replaced. And for that to take place, everyone on Kopra will have to be evacuated. This news is met with anger by the inhabitants of the garbage world. It’s up to Oliver Roach to gain their confidence and effect their removal.

‘Garbage World’ is a serviceable, but not particularly exciting, SF adventure. It’s not really a New Wave SF tale, but it does display the expanded approach to the genre that typified the New Wave ethos. By focusing on the sociology of the Kopran civilization and its uneasy relationship with the affluent worlds that enable it to survive in its own (rather deviant) manner, Platt was effectively prefiguring the ‘Garbage Mountain’ reality of Third World life in the present day.

Take, for example, the Payatas dump in the suburbs of Manilla:

As we come over a rise, my first glimpse of Payatas is hallucinatory: a great smoky-gray mass that towers above the trees and shanties creeping up to its edge. On the rounded summit, almost the same color as the thunderheads that mass over the city in the afternoons, a tiny backhoe crawls along a contour, seeming to float in the sky. As we approach, shapes and colors emerge out of the gray. What at first seemed to be flocks of seagulls spiraling upward in a hot wind reveal themselves to be cyclones of plastic bags. The huge hill itself appears to shimmer in the heat, and then its surface resolves into a moving mass of people, hundreds of them, scuttling like termites over a mound. From this distance, with the wind blowing the other way, Payatas displays a terrible beauty, inspiring an amoral wonder at the sheer scale and collective will that built it, over many years, from the accumulated detritus of millions of lives.

Hundreds of scavengers, brandishing kalahigs and sacks, faces covered with filthy T-shirts, eyes peering out like desert nomads' through the neck holes, gather in clutches across the dump. Gulls and stray dogs with heavy udders prowl the margins, but the summit is a solely human domain. The impression is of pure entropy, a mass of people as disordered as the refuse itself, swarming frantically over the surface. But patterns emerge, and as trucks dump each new load with a shriek of gears and a sickening glorp of wet garbage, the scavengers surge forward, tearing open plastic bags, spearing cans and plastic bottles with a choreographed efficiency.

In this regard, ‘Garbage World’ may be seen as an example of the ways in which SF can address topics and issues well in advance of other genres of literature.

Labels:

Garbage World

Thursday, September 9, 2010

'Heavy Metal' magazine September 1980

The September 1980 issue of 'Heavy Metal' featured 'It Came from Mount Saint Helens' by Robert Adragna on the front cover, and 'Who's the Fairest of Them All ?' by Berni Wrightson on the back cover.

Ongoing installments of Ribera and Godard's 'The Alchemist Supreme', Bilal's 'Progress', and Duillet's 'Salammbo' dominated this issue. Other noteworthy material included Kirchner's outstanding 'Shaman', which I will be posting later this month, and the amusing strip 'Into the Breach' by Shirley and Duranona.

I've posted the Salammbo strip below. In this episode Loan Sloane, obsessed with Salammbo and determined to risk his ship's safety in order to rondezvous with her, deals with a rebellious crew in rather abrupt fashion.....

Labels:

Heavy Metal September 1980

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)