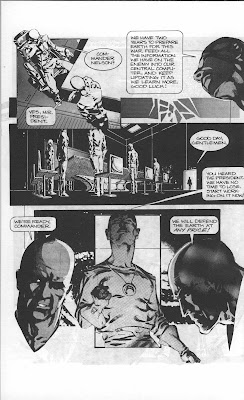

by Mike Deodato Sr and Mike Deodato Jr

Caliber Comics, 1996

Since the late 1980s, Mike Deodato, Jr (b. 1963) has established himself as a well-known and successful comic book artist for major publishers, including DC and Marvel. But his first forays into writing and illustrating comic books came in his native Brazil, and his very first comic book was a black and white title called Year 3000, released in 1984.

In 1996 U.S. publisher Caliber Comics negotiated with Deodato, Jr to release seven of his Brazilian comic books in English, including Year 3000, which was retitled Fallout 3000.

Produced in conjunction with his father, Mike Deodato Sr,who wrote the comic, Fallout 3000 is an impressive artistic debut, all the more so considering that Deodato Jr was only 21 at the time. The story starts out on a post-apocalyptic note (with one of the more intense illustrations of a Rat Attack that I've ever seen !) before transitioning into a broader landscape of interstellar war.

Deodato Jr's artwork is reminiscent of that of Paul Neary in the Warren magazines of the 1970s in its innovative and striking use of full-page, collage-based compositions, chiaroscuro, and Zip-A-Tone.

I've posted the entirety of Fallout 3000 below...........note that the original Caliber Comic book can be obtained, for a reasonable price, from online comic book vendors.

.jpg)