Saturday, November 21, 2009

Heavy Metal magazine November 1979

Monday, January 2, 2012

The Illustrated Harlan Ellison

‘The Illustrated Harlan Ellison’ (1978) was one of several trade paperbacks, in a groundbreaking graphic format, released by Baronet Publishers in the late 1970s under the auspices of ‘Byron Preiss Visual Publications’. The other volumes were ‘The Illustrated Roger Zelazny’, 1978; and ‘Alfred Bester's The Stars My Destination, Volume One: The Graphic Story Adaptation’, 1979.

There is a brief portfolio of paintings by Leo and Diane Dillon, Ellison's favorite artists.

The chapter devoted to an illustrated version of ‘“Repent, Harlequin !”, Said the Ticktockman’ is unusual in that Jim Steranko provided 3-D images, which the reader viewed with the aid of a pair of crude spectacles, with red and blue cellophane lenses, which were inserted into the book’s binding much like a detachable subscription renewal card. The 3-D effects genuinely work, and are another example of Steranko’s genius as an artist and designer. An article on Steranko's design process is available at this website dedicated to the drawings of the artist.

By and large the contents of ‘Ellison’ will appeal to fans of that author’s work. The ‘Croatoan’, ‘Discarded’, and ‘Glass Goblin’ pieces are outstanding, and ‘Dark Train’ also stands out.

The only real dud in this collection is ‘Kadak', which comes across as a too-contrived effort by Ellison to recover his Jewish Roots by working up a humorous fable heavily littered with Yiddish words and phrases.

Unfortunately, the high production costs of books like ‘Ellison’ were difficult to recoup through sales. The result was that Baronet went defunct in 1980. Back in the late 1970s the major retail outlets for books were the shopping mall-centered chain stories like Waldenbooks, and these retailers were just beginning to contemplate devoting precious store space to something as seemingly juvenile as paperback compilations of comics.

Indeed, if Baronet had started its line in the mid 80s, the chances of success would have been much higher. As is stands, they remain one of the early innovators of the graphic novel format that is widely represented in retail sf and fantasy commerce nowadays.

Friday, March 1, 2013

March, 1979, and on the radio, Bobby Caldwell's 'What you won't do for love' is getting substantial airplay. Released in 1978 on the album 'Bobby Caldwell', the song made it to No. 9 on Billboard's Hot 100 in 1979.

In the latest issue of Heavy Metal, Angus McKie provides the front cover, 'S*M*A*S*H', and Robert Morello the back cover, 'Stargazer'.

There are - alas - no stories by stalwarts Caza, Nicollet, Kirchner, and Suydam, leaving the reader to make do with ongoing installments of 'Sinbad', 'So Beautiful and So Dangerous', 'Starcrown', and 'Exterminator 17'.

There's an illustrated short story from Harlan Ellison titled 'Flopsweat', and a lengthy excerpt of the forthcoming illustrated novel 'Alfred Bester's The Stars My Destination' by Preiss and Chaykin.

The advertising is as quirky as ever.....indie comic publisher Star Reach offers its sf and fantasy books:

While 'Club Collection' rolling papers, and the Diddle Art company (marketing a 'Diddle It' poster) offer products of special interest to the stoners making up much of the HM readership.....

There are some good, shorter b & w pieces in the March issue, such as the pen-and-ink strip, 'A Mass for the Dead' by Pertuze, which evokes the penmanship of 19th-century illustrative art:

Chantal Montellier provides another subtle, but effective, episode of '1996' :

Sunday, February 17, 2013

Book Review: The Enemy of My Enemy

2 / 5 Stars

'The Enemy of My Enemy’(160 pp) was published in December 1966 by Berkley Medallion; the cover artwork is by Richard Powers.

On the planet Orinel, in the overpopulated, stinking, polluted land called Pemath, Jerrod Northi enjoys a successful career as a pirate and thief. However, as the novel opens, Northi finds himself the target of an assassination attempt by persons unknown.

Northi decides to flee Pemath. His preferred destination is Tarnis, a country located elsewhere on Orinel.

Idyllic and uncrowded, Tarnis is where everyone on Orinel would prefer to live. But the Tarnisi are very particular about who comes into their country, and for how long they are allowed to stay.

For Jerrod Northi, permanent residency in Tarnis can only come about through an exceedingly expensive transformation, courtesy of plastic surgery. The end result will give him the Seven Signs that identify one as a legitimate member of the Tarnisi race: green eyes, long fingers, long ears, hairless bodies, full mouths, slender feet, and melodious voices.

In due course Jerrod Northi finds himself transformed, renamed, given a plausible backstory, and a permanent resident in the promised land of Tarnis. There he settles into a life of ease and repose as a member of the aristocracy.

But as Northi becomes more aware of the internal politics of his adopted home, he also comes to a dismayed awareness that all might not be right with Tarnis….or its people….

When viewed as an SF novel originating in the mid-60s, just before the advent of the New Wave Movement, ‘Enemy’ is not particularly bad, but neither is it particularly memorable.

With ‘Enemy’, Davidson’s prose skills certainly are superior to those of Blish, Asimov, and Clarke, who tended to dominate the sf publishing arena of that time.

However, Davidson was not as accomplished in his plotting as those authors. ‘Enemy’ suffers from too-slow pacing, and its emphasis on wordplay quickly grows tiring. At its halfway point the novel does gain some energy through incidents of violence and brutality communicated in a surprisingly explicit manner for an sf novel of its time.

Unfortunately, however, the momentum from this device is soon dissipated, and the plot settles back into its rut. I have observed this to be a major weakness in other of Davidson’s lengthier works ('The Kar-Chee Reign' and 'Rogue Dragon' come to mind).

While hardcore Davidson fans may find ‘Enemy’ worthwhile, I suspect all others probably will find it rather dull; these I direct to Davidson’s short story collections, which are more rewarding.

Thursday, June 8, 2023

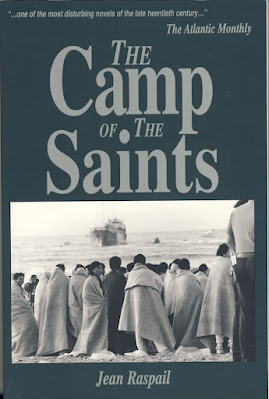

Book Review: The Camp of the Saints

Friday, April 4, 2014

Book Review: The Year's Best Horror Stories: Series XIV

2 / 5 Stars

‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series XIV’ (291 pp) is DAW Book No. UE2156 / 688, published in October, 1986. The cover art is by Michael Whelan.

All of the entries in this edition were first published in 1984 -1985, usually in the pages of other anthologies, or in magazines like The Twilight Zone Magazine, Interzone, and Night Cry.

There is a brief, two-page introduction by editor Karl Edward Wagner.

‘Series XIV’ is a standard-issue ‘Year’s Best’ compilation; in other words, the Usual Suspects are represented and accounted for: Ramsey Campbell, Dennis Etchison, Charles L. Grant, Tanith Lee.

My brief summary of the contents:

‘Penny Daye’, Charles L. Grant: mildly threatening British ghosts, ancient monuments, and the anomie of modern life. Another forgettable psychological horror tale from Grant.

‘Dwindling’, David B. Silva: Quiet Horror story about a boy whose family life is subject to unusual circumstances.

“Dead Men’s Fingers’, Philip C. Heath: in the South Pacific, the American whaler Reaper is found adrift, her crew vanished. One of the best stories in the anthology.

‘Dead Week’, Leonard Carpenter: a coed has unusual visions. Predictable, if competently written.

‘The Sneering’, Ramsey Campbell: British pensioners find life in a neighborhood undergoing urban renewal has its drawbacks. I wasn’t hoping for much from Campbell with this story, and he didn’t disappoint me........ Although it’s the first time I’ve ever read the sentence: ‘A car snarled raggedly past the gate.’ Cars …….snarling…..? Raggedly ? But then, who am I to say what is Art ?

‘Bunny Didn’t Tell Us’, David J. Schow: a burgeoning splatterpunk practitioner makes it into a DAW ‘Year’s Best’ anthology ! Hurrah ! Clever tale of grave-robbing gone bad…..because the grave belongs to a deceased pimp……!

‘Pinewood’, Tanith Lee: predictable tale about a grieving widow.

‘The Night People’, Michael Reaves: a hipster seeks solace for his angst by walking the city streets at night. I suspect most readers will guess the ending well in advance.

‘Ceremony’, William F. Nolen: a late-night bus ride leads to a creepy small town. Atmospheric, with a good ending; another of the better entries in this collection.

‘The Woman in Black’, Dennis Etchison: while employing his usual oblique, overly wordy prose in this story about a boy navigating a troubled neighborhood, Etchison makes this tale work by virtue of a bizarre ending.

‘Beside the Seaside, Beside the Sea’, Simon Clark: more a fragment rather than a genuine short story. Supernatural events at night, in a British seaside resort.

‘Mother’s Day’, Stephen F. Wilcox: a man attends to his nagging mother. Not really a horror story, but in fact a psychological drama.

‘Lava Tears’, Vincent McHardy: confused tale of a psycho killer.

‘Rapid Transit’, Wayne Allen Sallee: an aimless young man witnesses a murder in a train yard. Essentially plot-less, and badly overwritten by Sallee, who at the time was a poet trying his hand at short fiction.

‘The Weight of Zero’, John Alfred Taylor: not a short story per se, but actually the first chapter of a never-published novel…?! It’s never a good indicator of editorial competence when the editor has to use a first chapter of an unpublished novel in order to meet his obligation for a requisite number of entries….anyways, this is the vague tale of a Euro-hipster pursuing occult rituals.

‘John’s Return to Liverpool’, Christopher Burns: as you can guess, Dead Lennon is resurrected and visits his hometown. Relying on New Testament tropes, the story comes is too mawkish and insipid to be effective.

‘In Late December, Before the Storm’, Paul J. Sammon: unimaginative tale of a dissipated young man fated to relive a traumatic event. Sammon would go on to edit the seminal Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror anthology of 1990.

‘Red Christmas’, David Garnett: a murderer is on the loose, just before Christmas. I started this story thinking it was yet another clichéd ‘serial killer’ tale, but it provides a genuinely imaginative, offbeat ending. The best story in the anthology !

‘Too Far Behind Gradina’, Steve Sneyd: it’s not a good sign when a story in a horror anthology starts off with a really awful poem in blank verse….this despite the fact that the author is a published poet…..’Gradina’ is about a bored British housewife on vacation in Croatia; she follows a pair of German tourists, brother and sister, to a forbidding destination in the hills above the coast. This novelette was a true chore to finish, as it consisted of the type of run-on sentences, heavily overloaded with stilted, figurative prose, that typified SF writing of the New Wave era. It closes the anthology on a very unimpressive note.

The verdict ? ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series XIV’ is no better, and probably a little worse, then the other volumes in this series that were edited by Karl Edward Wagner. But hardcore horror short story aficionados may want it for the virtues of the tales by Heath, Schow, Nolen, and Garnett.

Saturday, June 8, 2013

Book Review: Set of Wheels

1 / 5 Stars

‘Set of Wheels’ (281 pp) was published by Berkley Books in February, 1983. The cover illustration is by Alan Daniels.

‘Set of Wheels’ is not a very good book. In fact, it was a struggle to finish..........

The novel is set in the early 21st century, after some poorly defined economic and / or social collapse has transformed the nation into a loose collection of city-states. Outside the cities the landscape is slowly being depopulated, the highways are abandoned, and drifters, outcasts, criminals, the destitute, and religious fanatics control the dwindling numbers of small towns, road stops, and villages.

Within the cities, car ownership is heavily regulated (drivers must obtain a ‘safdry’ license). Vehicles are prohibited from travelling at high speeds, drivers are subject to random police checkpoints, and even minor moving violations can result in the permanent loss of a license.

Teenager Lee Kestner is bored, sullen, and rebellious. Not only is living with his alcoholic father depressing, but Lee has been turned down for a learner’s permit 17 times. Desperate to get his own set of wheels, and to experience the freedom of independent travel, Lee hands $500 over to his onetime friend Lincoln Rockwell X. In return, Lee gets a barely-running, beat-up, antique, 1967 Ford Mustang.

Despite the questionable mechanical status of his newly acquired car, Lee promptly takes off for the unregulated countryside outside the city limits. There he joins up with a loose coalition of outlaw drivers, gets his Mustang fixed up, and enters into a tumultuous romance with a girl named Cora.

Before long, Lee finds himself heading out across the under-populated landscape of the USA, unsure of his destination, but convinced that somewhere out on the open road, he will find purpose for a life otherwise marked by aimlessness and spiritual anomie.

‘Wheels’ is not much of an sf novel. Indeed, the sf elements are very muted, and serve as a sort of vague backdrop to the central goal of the narrative, which is to allow author Thurston to write lengthy, tedious passages of dialogue in which his characters expound on their existential despair.

Thurston’s efforts to impart a wistful, melancholy atmosphere to the activities of his modern-day nomads seems contrived and unconvincing. Let’s face it, whether made in 1967, 1975, 1982, 1996, or even today, the Ford Mustang always has been a piece of shit car, relying on its ‘cool’ appearance, and industry myth-making, to screen the fact that it has always been shoddily designed, shoddily manufactured, and overly prone to mechanical breakdowns.

(Although, to be fair, the same thing can be said about practically every vehicle made by Ford….)

To make things worse, Thurston adopts the affectation of eschewing quotation marks to set off dialogue. Readers will need to supply the patience to decipher these sorts of exchanges:

Get us out of here.

Her smile vanishes. Logical, perhaps, it’s been a ghost-smile.

Not a chance, honey.

But you and me, we-

I know what we done, but that’s just ice in the Amazon, far as I’m concerned.

If you’re hoping for something that resembles George Miller’s ‘Mad Max’ and ‘The Road Warrior’, or John Jake’s ‘On Wheels’, then you’re very much out of luck. The few episodes of action that take place in ‘Set of Wheels’ seem forced and tangential.

My recommendation ? ‘Set of Wheels’ is best avoided, unless you are adamant about reading any and all sf novels with a 'car' theme.

Wednesday, July 12, 2023

Book Review: The City: 2000 A.D.

Saturday, January 11, 2025

Book Review: The Death Cycle

‘The Death Cycle’ (159 pp.) was published by Fawcett’s Gold

Medal imprint in January 1963, as number s1268.

Charles W. Runyon (1928-2015) wrote a sizeable number of short stories and novels in the mystery, private eye, and sf genres during the 60s and 70s. Some of these saw publication under the house name 'Ellery Queen'. I consider his 1971 novel ‘Pig World’ to be an interesting, overlooked example of proto-Cyberpunk, while ‘Soulmate’ (1974) is a reasonably effective horror novel.

As ‘The Death Cycle’ opens our protagonists, Brett Phelan and his wife Jeanne, and Carl Newsome and his wife Doris, are on motorcycles, and on the run. It turns out that they have stolen $65,000 and are fleeing Chicago, where a jeweler was shot dead in the course of a robbery, for Southern Mexico.

Brett is not the nicest of men, and there is a rivalry between he and Carl that goes back to the days when they served in the same unit during the Korean War. For his part, Carl dislikes and distrusts Brett, but realizes that until they reach safety in Mexico, the two are obliged to work together.

Doris and Jeanne are complete opposites. Doris is, in the parlance of early 60 pulp fiction, a ‘nympho’ who constantly craves attention, while Jeanne’s life as Brett’s spouse has left her steeped in misery……and bruises.

As the couples travel ever closer to their final destination, where the money is to be split and separate ways taken, the likelihood of a double-cross looms ever larger. And the man to deliver it will be a sadistic Mexican pistolero nicknamed ‘Trinidad’…………

‘The Death Cycle’ is a serviceable, if not particularly imaginative, example of early 60s noir fiction. The novel is suffused with hard-boiled language, and here are some examples:

His blue eyes measured the world from a face that was locked up tight, like a house shuttered from a storm.

****

Sometimes she looked at them with the shocked fascination of a girl caught up in a lynch mob on her way to Sunday school.

****

When Frieda’s husband was away, her mind roiled with sexual fantasies which would make a Ciudad Juarez puta squirm uncomfortably on her pallet.

****

I’ve got a nose for death, thought Brett. I can smell people who are about to die.

***

And I encountered, for the first time in my life, the noun (?) ‘asininity’ within the pages of ‘The Death Cycle.’

I won’t disclose any spoilers, save to say that the conflict between Brett and Carl is resolved in a satisfactory way.

The verdict ? Those who like crime and suspense novels from the Gold Medal catalogue probably will find ‘The Death Cycle’ rewarding. Those accustomed to more sophisticated styles of writing may be disappointed.

.jpg)