Book Review: 'Among the Dead' by Edward Bryant

3 / 5 Stars

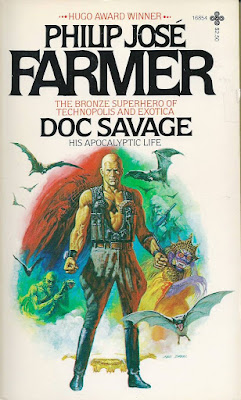

'Among the Dead' (210 pp.) was issued in 1974 by Collier Books. The cover art is by Grey Morrow, and it's not very good. In fact, it's among the worst cover art I've ever seen for a sci-fi paperback.

Edward Bryant (1945 - 2017) was a leading writer during the New Wave era. His short stories readily were labeled as 'speculative fiction,' and most of the 17 tales presented in 'Among the Dead' adhere to this label. These stories saw print in such anthologies as 'Clarion,' 'Quark,' 'New Dimensions,' and 'Orbit,' all prominent New Wave outlets.

Reading this anthology reminds me that for every imaginative and powerful story the New Wave era produced, there were a bunch of other stories that were failures.

In 'Among the Dead,' the failures are plentiful. I mean, one story bears the title 'No. 2 Plain Tank Auxiliary Fill Structural Limit 17,605 lbs. Fuel PWA Spec. 522 Revised,' which is sheer New Wave self-indulgence, and the sort of stuff editors like Damon Knight and Robert Silverberg thought was just so, so precious, back in the early seventies.

I won't bother to synopsize 'The Hanged Man', 'Jody After the War,' 'Sending the Very Best,' 'Love Song of Herself,' 'Their Thousandth Season,' 'Pinup,' and 'Dune's Edge,'because there's really not much there to synopsize. Just figurative prose, with no plot.

For example, in 'Dune's Edge,', a group of people find themselves stranded at a beach where they are compelled to climb to the top of a nearby sand dune. The narrator has some bad dreams. That's the plot. Just your average ordinary Existential Crisis.

'Teleidoscope' is about Markham, his struggles with impotence, his abuse during childhood at the hands of his mother, and his relationship with a woman named Cara. There are allusions to black holes and collapsing stars. This story is so New-Wavey that it's an unwitting parody of a New Wave story...............

'The Poet in the Hologram in the Middle of Prime Time' is reasonably coherent, plot-wise. It's about a new form of 3D television being marketed by the UniComp corporation, a form of TV that lets the viewer interact with the characters on-screen. A poet named Ransom, who supports himself by writing scripts for UniComp, sees this advance as a threat to Art, and contemplates taking drastic action to subvert the process. The story tries to say something Profound about the nature of Art in the futuristic society.

And the aforementioned 'No. 2 Plain Tank Auxiliary Fill Structural Limit 17,605 lbs,' is all about a political activist on a mission.

Also dealing with politics, with a helping of The Parallax View - style 70s paranoia, is 'Tactics,' which unfortunately has too vague an ending to be effective.

The thing about Bryant is, when he wanted to, he could write very good stories. And there are some of these in the pages of 'Among the Dead.' Stories that are well-constructed and well-plotted.

Among the best of these is 'The Human Side of the Village Monster,' which, despite its cumbersome title, is a very good tale about a near-future New York City ruined by overpopulation and Eco-Catastrophe. It seems to have a predictable denouement, but veers off into an unexpected, but unpleasant, direction. I've placed this story in my list of top horror stories of the 1960s to the early 1990s.

The title story also is well-done. It takes a familiar theme: the Last People on Earth, and their struggle for survival, and imbues these with a dark humor that calls to mind Harlan Ellison at his transgressive best.

Also worthy is 'Shark,' in which the first-person narrator's girlfriend has her brain transplanted into that very animal. It's a sort of warped version of the 1973 movie The Day of the Dolphin.

'Adrift on the Freeway' deals with entropy and middle-aged angst, and while the ending is a little too ambiguous for me, it does capture existential anomie as well as any New Wave era piece did.

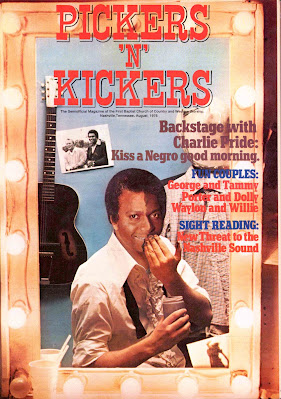

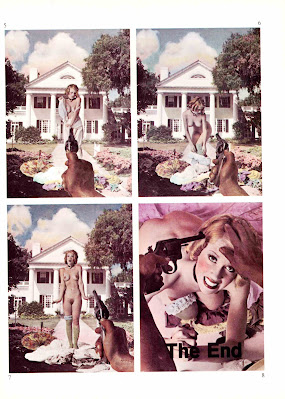

An oddity in this collection is 'File on the Plague,' which first appeared in the April, 1971 issue of the National Lampoon. As one might expect, it's a humorous piece.........sheep are involved. I'll just post scans of the story, and let you decide whether it has merit........

'The Soft Blue Bunny Rabbit Story' focuses on a college student caught up in campus unrest; the situation is made worse - or perhaps better - by his use of hallucinogens.

Summing up, there are enough good stories in 'Among the Dead' to justify giving the anthology a Three Star Rating.

.jpg)