Book Review: 'Breakthrough' by Richard Cowper

1 / 5 Stars

‘Breakthrough’ was first published in 1967 in hardcover; this Ballantine paperback (218 pp.) was issued in July 1969. The oustanding cover illustration is by Steele Savage.

[‘Richard Cowper’ was the pseudonym of the British author John Middleton Murry, Jr.]

It’s the Summer of 1964, and on the campus of Hampton University in England, newly hired English professor Jimmy Haverill befriends a fellow professor, ‘Dumps’ Dumpkenhoffer.

An American, and something of an eccentric, Dumps runs the Parapsychology Research Department, a unit housed in an older building on the campus. Haverill visits the parapsychology laboratory and witnesses students engaged in experiments reminiscent of those conducted by J. B. Rhine at Duke University in the 1940s; i.e., students are asked to guess which of five symbols are printed on the face of 25 playing cards. Correctly guessing the identity of a certain percentage of the cards may be taken as an indicator of some form of ESP.

Only half-serious about the concept, Haverill has a go at the psy ability test, and to Dumps’s astonishment, performs unusually well. Does Haverill have genuine parapsychological powers ? Perhaps – but the plot deepens when an attractive coed, Rachel Bernstein, also displays considerable aptitude at the symbol-guessing test. It appears that there is some sort of ‘psychic’ link between Haverill and Bernstein.

In due course, the two test subjects progress from acquaintances to romantic partners. Along with this progression comes a realization that the two of them are capable of additional psychic powers, including out-of-body experiences, some of which involve mysterious dreamscapes, and the presence of entities from what may be another dimension.

As Rachel Bernstein becomes more engrossed in these strange phenomena, it’s up to Dumps to discover a way to understand the connection between the two worlds, before a psychic implosion threatens Rachel's sanity - and even her life.

‘Breakthrough’ was one of Cowper’s early novels, and as such, it’s unremarkable. It’s really more of a romance novel, than a sf novel.

The narrative moves at a very slow pace, and centers on the emotional interactions of the main characters, rather than the parapsychological phenomena which occupy the backstory.

Cowper devotes most of his narrative to conversational exchanges, which often feature first-person narrator Haverill using words and phrases from British slang that were painfully outdated even at the time of writing. (For example, readers will quickly tire of Haverill’s use of ‘old thing’ as a term of affection for his girlfriend).

These conversational exchanges are reasonably well-written, and signal that in this regard, Cowper is a capable author. But in the absence of a compelling plot, they alone cannot make up for the novel’s shortcomings.

In short, ‘Breakthrough’ is rather a dull and unimaginative novel, and even Cowper completists will find little to engage them here. Better things were to come from this author as his writing career progressed.

Friday, October 19, 2012

Labels:

Breakthrough

Tuesday, October 16, 2012

'The Eyes of the Cat'

('Los Ojos del Gato', 'Les Yeux du Chat')

by Jodorowsky and Moebius

from Metal Hurlant No. 1 (Spanish-language version)

To the best of my knowledge, 'The Eyes of the Cat', taken here from the Spanish-language version of Metal Hurlant No. 1 (1981), was never republished in the Leonard Mogel / US version of the magazine.

It did appear in 1991 in issue No. 4 of the notorious Taboo graphic novel series, and this past August, Humanoids republished the strip in a hardcover edition, in English, available at amazon for $23.00.

'Eyes of the Cat' first appeared in 1978, as a specially-printed hardcover book, distributed as a gift to subscribers and friends and acquaintances of the Metal Hurlant staff.

It's unfortunate it never made it to Heavy Metal, because 'Eyes' is one of the creepiest, as well as brilliant, comics to appear in any edition of Metal Hurlant.

The dialogue, however scant, neatly matches the narrative, and the passage of each panel - which are presented in a novel, but visually effective, side-by-side format - lets the story unfold with just the right pacing all the way to its final, disturbing sentence.

All this, and some brilliant pen-and-ink work by Moebius.

This comic was miles (light years ?) ahead of anything in the Marvel or Warren catalog of black and white horror comics of the 1970s / 1980s.

[My translation into English is paraphrased and not literal, but hopefully it gets the job done.]

('Los Ojos del Gato', 'Les Yeux du Chat')

by Jodorowsky and Moebius

from Metal Hurlant No. 1 (Spanish-language version)

To the best of my knowledge, 'The Eyes of the Cat', taken here from the Spanish-language version of Metal Hurlant No. 1 (1981), was never republished in the Leonard Mogel / US version of the magazine.

It did appear in 1991 in issue No. 4 of the notorious Taboo graphic novel series, and this past August, Humanoids republished the strip in a hardcover edition, in English, available at amazon for $23.00.

'Eyes of the Cat' first appeared in 1978, as a specially-printed hardcover book, distributed as a gift to subscribers and friends and acquaintances of the Metal Hurlant staff.

It's unfortunate it never made it to Heavy Metal, because 'Eyes' is one of the creepiest, as well as brilliant, comics to appear in any edition of Metal Hurlant.

The dialogue, however scant, neatly matches the narrative, and the passage of each panel - which are presented in a novel, but visually effective, side-by-side format - lets the story unfold with just the right pacing all the way to its final, disturbing sentence.

All this, and some brilliant pen-and-ink work by Moebius.

This comic was miles (light years ?) ahead of anything in the Marvel or Warren catalog of black and white horror comics of the 1970s / 1980s.

[My translation into English is paraphrased and not literal, but hopefully it gets the job done.]

The Eyes of the Cat

I feel hot....

Finally, a sunbeam !

Attention, Meduz: go out !

I hear his footsteps

There he is....

Very good...fast, Meduz !

Descend !

Bravo, Meduz !

Do not forget to keep my eyes....

It's marvellous !

I'm playing at seeing....

Next time, bring me the eyes of a child......

Saturday, October 13, 2012

Book Review: Nightmares

Book Review: 'Nightmares' edited by Charles L. Grant

According to editor Grant, about half of the entries were written specifically for this anthology. The remainder are tales that were first printed in various 'slick' and digest magazines throughout the 70s.

Charles L. Grant (1942 - 2006) was of course one of the leading practitioners of 'Quiet Horror' in the interval from the late 70s to the late 90s. I always was underwhelmed by Grant's stories, and those of the other Quiet Horror authors that he routinely selected for his anthologies (the 'Shadows' series comes quickly to mind).

[For an expanded take on Charles Grant's anthologies, readers are directed to the Too Much Horror Fiction blog.]

'Nightmares' is actually a passable anthology. While certainly none of the stories would qualify as hardcore grue n' gore, most of the contributors avoid the Psychological Horror treadmill in favor of more imaginative takes on the horror genre. Whether this is because of Grant's editorial insistence, or happy chance, is unclear.

There are a number of short-short stories. 'Peekaboo' by Bill Pronzini, 'Unknown Drives' by Richard Christian Matheson, 'I Can't Help Saying Goodbye' by Anne Mackenzie, 'Mass Without Voices' by Arthur L. Samuels, 'The Anchoress' by Beverly Evans, and 'He Kilt It With A Stick' by William F. Nolan, all are competent exercises in surprise / shock endings.

Avram Davidson's 'Naples' is, as are all his stories, consciously 'literary', but its atmospheric setting and subdued, but effective, ending, makes it one of the best entries in the collection.

Steven King's contributions to horror anthologies in the 70s and 80s could be hit-or-miss. 'Suffer the Little Children', first printed in 1972, is one of his superior entries. It's an able depiction of unpleasant schoolkids.

'The Night of the Piasa' by G. W.Proctor and J. C. Green, and 'Snakes and Snails' by J. C. Haldeman II, have a retro, Weird Tales - style pulp sensibility. The former story, in particular, suffers from amateurish prose.

'Seat Partner' by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro is not even a horror tale, but rather, an opening chapter from one of her Count St. Germain novels. The inclusion of this fragment in the anthology is a mystery; it could have been that Yarbro was caught at deadline time with nothing ready for editor Grant (there was no such thing as email in 1979, so manuscripts had to be snail-mailed).

Inevitably for a 70s horror anthology, Ramsey Campbell is present and accounted for. 'Midnight Hobo' starts off well despite Campbell's clotted prose, and, somewhat surprisingly, maintains sufficient momentum to its last sentence to serve as a reasonably decent horror story.

Treasure it; rewarding Campbell pieces such as 'Hobo', are very few and far between.

Summing up, 'Nightmares' is a decent enough late-70s anthology of horror tales. There are some worthy entries here, that making trudging trough the subpar material worthwhile.

3 / 5 Stars

'Nightmares' (256 pp.) was released by Playboy Books in September 1979; the cover artwork is by Alfred Pisano.

According to editor Grant, about half of the entries were written specifically for this anthology. The remainder are tales that were first printed in various 'slick' and digest magazines throughout the 70s.

Charles L. Grant (1942 - 2006) was of course one of the leading practitioners of 'Quiet Horror' in the interval from the late 70s to the late 90s. I always was underwhelmed by Grant's stories, and those of the other Quiet Horror authors that he routinely selected for his anthologies (the 'Shadows' series comes quickly to mind).

[For an expanded take on Charles Grant's anthologies, readers are directed to the Too Much Horror Fiction blog.]

It goes without saying that Splatterpunks were not tolerated by Grant, and those purveyors of that genre during the 70s (James Herbert comes readily to mind) are absent from this volume.

'Nightmares' is actually a passable anthology. While certainly none of the stories would qualify as hardcore grue n' gore, most of the contributors avoid the Psychological Horror treadmill in favor of more imaginative takes on the horror genre. Whether this is because of Grant's editorial insistence, or happy chance, is unclear.

There are a number of short-short stories. 'Peekaboo' by Bill Pronzini, 'Unknown Drives' by Richard Christian Matheson, 'I Can't Help Saying Goodbye' by Anne Mackenzie, 'Mass Without Voices' by Arthur L. Samuels, 'The Anchoress' by Beverly Evans, and 'He Kilt It With A Stick' by William F. Nolan, all are competent exercises in surprise / shock endings.

Avram Davidson's 'Naples' is, as are all his stories, consciously 'literary', but its atmospheric setting and subdued, but effective, ending, makes it one of the best entries in the collection.

Steven King's contributions to horror anthologies in the 70s and 80s could be hit-or-miss. 'Suffer the Little Children', first printed in 1972, is one of his superior entries. It's an able depiction of unpleasant schoolkids.

Dennis Etchison, a dedicated practitioner of Quiet Horror, provides 'Daughter of the Golden West'. Dealing with high school boys looking into the fate of a missing comrade, 'Daughter' labors under Etchison's opaque prose style. But the tale's final page avoids the ambiguous, deliberately vague endings too common to Etchison stories. This also is one of the better entries in this anthology.

'The Duppy Tree', by Steven McDonald, is a novel take on Jamaica, and its folk mythology.

'Camps', by Jack Dann, involves a sickly man who has disturbing dreams about a concentration camp. It's an overly contrived effort to construct a psychological horror story around the theme of the Holocaust.

'The Night of the Piasa' by G. W.Proctor and J. C. Green, and 'Snakes and Snails' by J. C. Haldeman II, have a retro, Weird Tales - style pulp sensibility. The former story, in particular, suffers from amateurish prose.

Barry Malzburg's 'Transfer' is an overly wordy examination of the mind of serial killer.

'Fisherman's Log' by Peter D. Pautz, and 'The Ghouls' by R. Chetwynd - Hayes, take satirical looks at encounters with aquatic, and zombie, monster manifestations, respectively.

'Seat Partner' by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro is not even a horror tale, but rather, an opening chapter from one of her Count St. Germain novels. The inclusion of this fragment in the anthology is a mystery; it could have been that Yarbro was caught at deadline time with nothing ready for editor Grant (there was no such thing as email in 1979, so manuscripts had to be snail-mailed).

'The Runaway Lovers', a old (1967) tale from Ray Russell, is less horror, than a sardonic look at human foibles.

Inevitably for a 70s horror anthology, Ramsey Campbell is present and accounted for. 'Midnight Hobo' starts off well despite Campbell's clotted prose, and, somewhat surprisingly, maintains sufficient momentum to its last sentence to serve as a reasonably decent horror story.

Treasure it; rewarding Campbell pieces such as 'Hobo', are very few and far between.

Summing up, 'Nightmares' is a decent enough late-70s anthology of horror tales. There are some worthy entries here, that making trudging trough the subpar material worthwhile.

Labels:

Nightmares

Thursday, October 11, 2012

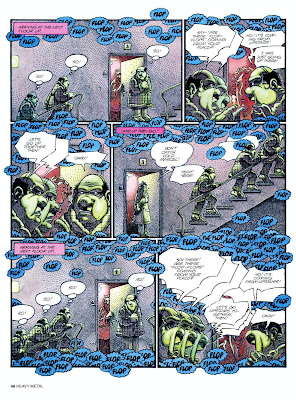

The Horror of G' Zalth by Brocal Remohi

'The Horror of G' Zalth' by Brocal Remohi

from Heavy Metal magazine, September, 1978

Outstanding artwork, and a fun conclusion, define this barbarian / sword and sorcery tale by Spanish artist Jaime Brocal Remohi, who also produced some fine work for Warren's Creepy and Eerie magazines in the early 70s.

from Heavy Metal magazine, September, 1978

Outstanding artwork, and a fun conclusion, define this barbarian / sword and sorcery tale by Spanish artist Jaime Brocal Remohi, who also produced some fine work for Warren's Creepy and Eerie magazines in the early 70s.

Labels:

The Horror of G' Zalth

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

Heavy Metal magazine October 1982

'Heavy Metal' magazine October 1982

The October 1982 issue of Heavy Metal is designed to be a 'horror' - themed issue. While it certainly features a striking front cover by Jim Burns, and a back cover by Alan Lynch, the interior contents are very run-of-the-mill.The truth is, as a 'horror special' the October issue is a disappointment, nothing at all like the memorable 'Lovecraft' special issue of three years previously.

The Dossier section leads off with reviews of new New wave / Punk records; bands such as The Cure, Bauhaus, and New Order are of course recognizable, but when Rok Critic Lou Stathis includes the group 'You've Got Footus On My Breath' as his 'current favorite' band, you know he's trying much too hard to be hip....but then, what else was new.....

The Dossier moves on to discuss awful and obscure horror films - some of these I've never heard of before, and I subscribe to Shock Cinema (!). The 'Spook Shelf' section reviews some horror novels that also seem obscure - perhaps they will show up (or have already been reviewed) at Too Much Horror Fiction.

The Dossier continues with an interview with David Lynch, riding high on the success of the film The Elephant Man, and prepping for the film Dune. The latter, or course, was to be Lynch's Waterloo, but at this moment in time, his future as a director looked limitless.

The Dossier closes with some Science Notes, and some brief reviews of the current crop of video games.

As far as the comic content of this issue of HM, we have new installments of Wrightson's 'Freak Show', Corben's 'Den II', 'The Ape' by Pisu and Manera, 'Yragael' by Druillet, and 'Zora' by Fernandez. There is an essay on modern horror and phobias by Jeff Goldberg, and the third installment in 'The Third Sexual Revolution' series of essays by David Black.

Caza comes through with a colorful strip titled 'The Blind Flock'; I've posted it below.

The October 1982 issue of Heavy Metal is designed to be a 'horror' - themed issue. While it certainly features a striking front cover by Jim Burns, and a back cover by Alan Lynch, the interior contents are very run-of-the-mill.The truth is, as a 'horror special' the October issue is a disappointment, nothing at all like the memorable 'Lovecraft' special issue of three years previously.

The Dossier section leads off with reviews of new New wave / Punk records; bands such as The Cure, Bauhaus, and New Order are of course recognizable, but when Rok Critic Lou Stathis includes the group 'You've Got Footus On My Breath' as his 'current favorite' band, you know he's trying much too hard to be hip....but then, what else was new.....

The Dossier moves on to discuss awful and obscure horror films - some of these I've never heard of before, and I subscribe to Shock Cinema (!). The 'Spook Shelf' section reviews some horror novels that also seem obscure - perhaps they will show up (or have already been reviewed) at Too Much Horror Fiction.

The Dossier continues with an interview with David Lynch, riding high on the success of the film The Elephant Man, and prepping for the film Dune. The latter, or course, was to be Lynch's Waterloo, but at this moment in time, his future as a director looked limitless.

The Dossier closes with some Science Notes, and some brief reviews of the current crop of video games.

As far as the comic content of this issue of HM, we have new installments of Wrightson's 'Freak Show', Corben's 'Den II', 'The Ape' by Pisu and Manera, 'Yragael' by Druillet, and 'Zora' by Fernandez. There is an essay on modern horror and phobias by Jeff Goldberg, and the third installment in 'The Third Sexual Revolution' series of essays by David Black.

Caza comes through with a colorful strip titled 'The Blind Flock'; I've posted it below.

Labels:

'Heavy Metal' October 1982

Friday, October 5, 2012

Book Review: Heritage of the Star

Book Review: 'Heritage of the Star' by Sylvia Engdahl

3 / 5 Stars

‘Heritage of the Star’ (January 1976, Puffin, 250 pp., cover artist uncredited) was originally published in 1972 in the US under the title ‘This Star Shall Abide’.

‘Heritage’ is one of three volumes in the ‘Children of the Stars’ series, the others being ‘Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains’, and ‘The Doors of the Universe’, all originally published in the early 70s, and all intended for the Young Adult readership.

The trilogy has just this year been re-released in a 600+ page omnibus edition, titled, appropriately enough, ‘Children of the Stars’.

‘Heritage’ is set on an unnamed desert planet that is marginally superior, as a dwelling-place, to Tatooine. The people live hard-working, somewhat threadbare lives centered on an agrarian society operating at a medieval level of technology. The exception to this state of affairs is the walled City, where more advanced technology is centered, and where live members of the Technicians and Scholars castes.

The Technicians travel via landspeeders to the surrounding countryside to apply fertilizer to crops, render drinking water potable, and attend to the ill and injured, among other sundry duties. The Technicians do not share their technological bounty with the populace; metal is scarce, machines rare, and things like books are rarely seen outside the City walls.

The Scholars are remote and mysterious, more like priests than academics. They never venture beyond the courtyard of the front gates of the City, but spend their time inculcating the populace in a belief system revolving around a holy Prophecy, which foretells the advent of a wondrous new era of technological advances and bountiful living, when the ‘Mother Star’ appears in the sky – this at some undetermined point in the future.

Noren is a thoughtful young man living in a village in the hinterland. As the novel opens, his coming of age ceremony is underway, but Noren is dissatisfied with the prospect of marrying his school sweetheart, begetting children, and living out his days as a farmer.

Noren is troubled, even resentful, of the way that the Technicians and Scholars enjoy advanced technology, flitting about the landscape in their speeders even as the Lumpen Proletariat sweatily toil in the fields. Why should the Technicians be allowed the use of machines, when such things better could be used to abolish the drudgery of life in the villages ? Why should books – and by extension Knowledge - be kept within the City, and not distributed to the People ?

Noren even entertains heretical notions: he questions the validity of the Prophecy, and the creed of the Mother Star. Expressing such thoughts aloud can get one killed. But as Noren’s resentment of his lot in life grows, he decides to confront the ruling castes.

By so doing, Noren embarks on a fateful journey that will render him a prisoner of the Scholars, and a witness to the underlying truth of the society that governs life on his planet. The revelations will be cruel and unrelenting – but Noren is adamant that he will not turn back…..

‘Heritage’ belongs to the sub-genre of sf in which a young person risks life and limb to question the inflexible orthodoxy of his or her society – only to find their presuppositions replaced, in a wrenching fashion, by a carefully hidden reality.

Leigh Brackett’s classic novel ‘The Long Tomorrow’ comes most readily to mind as an example of this sub-genre. However, while Leigh Brackett was willing and able to use episodes of overt violence and confrontation to propel her narrative, in ‘Heritage’, author Engdahl takes too deliberate and restrained a tone, and her novel suffers in comparison.

Thus, while the opening chapters of ‘Heritage’ are certainly engaging, the middle portion of the novel tends to lose momentum, as author Engdahl belabors the philosophical exchanges between a defiant Noren and his captors. The climax of the novel – an episode of self-abnegation – is underwhelming, and leaves little room for anything other than a predictable conclusion.

Summing up, ‘Heritage’ is a well-written YA sf novel, and those who are content with a measured, contemplative tone will enjoy reading it.

But I strongly suspect that modern-era YA readers, accustomed to the strong, action-based content of novels such as those in the ‘Hunger Games’ series, will find ‘Heritage’ too sedate to be very rewarding.

3 / 5 Stars

‘Heritage of the Star’ (January 1976, Puffin, 250 pp., cover artist uncredited) was originally published in 1972 in the US under the title ‘This Star Shall Abide’.

‘Heritage’ is one of three volumes in the ‘Children of the Stars’ series, the others being ‘Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains’, and ‘The Doors of the Universe’, all originally published in the early 70s, and all intended for the Young Adult readership.

The trilogy has just this year been re-released in a 600+ page omnibus edition, titled, appropriately enough, ‘Children of the Stars’.

‘Heritage’ is set on an unnamed desert planet that is marginally superior, as a dwelling-place, to Tatooine. The people live hard-working, somewhat threadbare lives centered on an agrarian society operating at a medieval level of technology. The exception to this state of affairs is the walled City, where more advanced technology is centered, and where live members of the Technicians and Scholars castes.

The Technicians travel via landspeeders to the surrounding countryside to apply fertilizer to crops, render drinking water potable, and attend to the ill and injured, among other sundry duties. The Technicians do not share their technological bounty with the populace; metal is scarce, machines rare, and things like books are rarely seen outside the City walls.

The Scholars are remote and mysterious, more like priests than academics. They never venture beyond the courtyard of the front gates of the City, but spend their time inculcating the populace in a belief system revolving around a holy Prophecy, which foretells the advent of a wondrous new era of technological advances and bountiful living, when the ‘Mother Star’ appears in the sky – this at some undetermined point in the future.

Noren is a thoughtful young man living in a village in the hinterland. As the novel opens, his coming of age ceremony is underway, but Noren is dissatisfied with the prospect of marrying his school sweetheart, begetting children, and living out his days as a farmer.

Noren is troubled, even resentful, of the way that the Technicians and Scholars enjoy advanced technology, flitting about the landscape in their speeders even as the Lumpen Proletariat sweatily toil in the fields. Why should the Technicians be allowed the use of machines, when such things better could be used to abolish the drudgery of life in the villages ? Why should books – and by extension Knowledge - be kept within the City, and not distributed to the People ?

Noren even entertains heretical notions: he questions the validity of the Prophecy, and the creed of the Mother Star. Expressing such thoughts aloud can get one killed. But as Noren’s resentment of his lot in life grows, he decides to confront the ruling castes.

By so doing, Noren embarks on a fateful journey that will render him a prisoner of the Scholars, and a witness to the underlying truth of the society that governs life on his planet. The revelations will be cruel and unrelenting – but Noren is adamant that he will not turn back…..

‘Heritage’ belongs to the sub-genre of sf in which a young person risks life and limb to question the inflexible orthodoxy of his or her society – only to find their presuppositions replaced, in a wrenching fashion, by a carefully hidden reality.

Leigh Brackett’s classic novel ‘The Long Tomorrow’ comes most readily to mind as an example of this sub-genre. However, while Leigh Brackett was willing and able to use episodes of overt violence and confrontation to propel her narrative, in ‘Heritage’, author Engdahl takes too deliberate and restrained a tone, and her novel suffers in comparison.

Thus, while the opening chapters of ‘Heritage’ are certainly engaging, the middle portion of the novel tends to lose momentum, as author Engdahl belabors the philosophical exchanges between a defiant Noren and his captors. The climax of the novel – an episode of self-abnegation – is underwhelming, and leaves little room for anything other than a predictable conclusion.

Summing up, ‘Heritage’ is a well-written YA sf novel, and those who are content with a measured, contemplative tone will enjoy reading it.

But I strongly suspect that modern-era YA readers, accustomed to the strong, action-based content of novels such as those in the ‘Hunger Games’ series, will find ‘Heritage’ too sedate to be very rewarding.

Labels:

Heritage of the Star

Thursday, October 4, 2012

'The Barnyard' by Judson Huss

1986, oil on panel, 27 x 35 cm

from the book River of Mirrors: The Fantastic Art of Judson Huss

Morpheus International, 1996

1986, oil on panel, 27 x 35 cm

from the book River of Mirrors: The Fantastic Art of Judson Huss

Morpheus International, 1996

Labels:

The Barnyard by Judson Huss

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

Labels:

Punk Zone by Saenz and Daley

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)