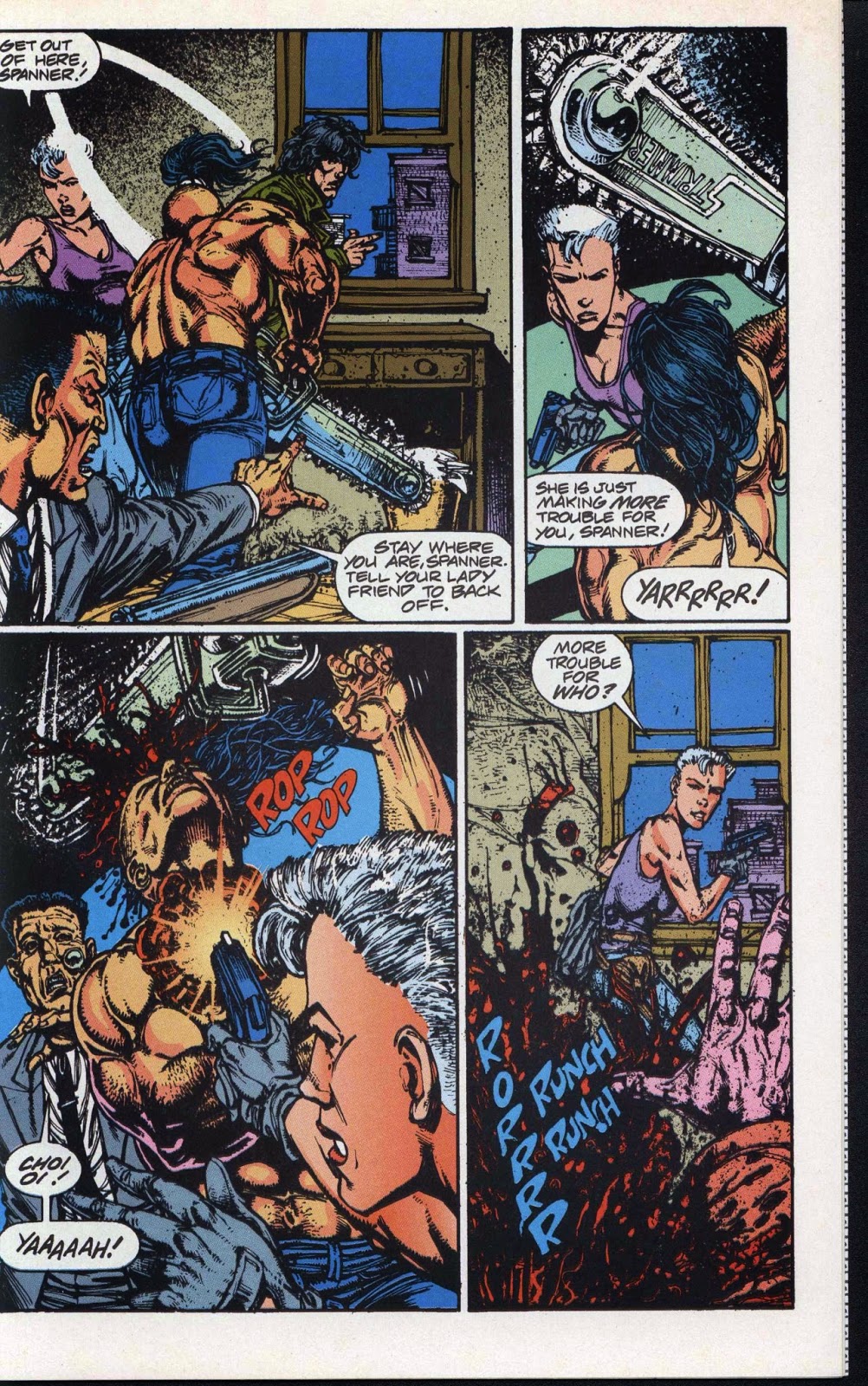

Car Warriors

issue 2

Epic Comics / Marvel, July, 1991

Issue 2 of 'Car Warriors' introduces some supporting characters, including Diamond, the punk rock chick; Spanner, the ace mechanic who keeps pissing off the wrong people; and my favorites, the Wysocki family: mom Agnes, dad Curt, daughter Sissy, and son Curt Jr. We learn that the 'Wysockis don't run from a fight !'

As word of the Big Race spreads, it becomes clear that the bandits and mutants of the Wasteland are in no mood to be accommodating......

Here it is, the second installment of 'Car Warriors'............

Friday, October 17, 2014

Monday, October 13, 2014

Book Review: The Harp of the Grey Rose

Book Review: 'The Harp of the Grey Rose' by Charles de Lint

4 / 5 Stars

‘The Harp of the Grey Rose’ first was published in 1985; this Avon Books paperback (230 pp) was released in February, 1991, and features cover artwork by Darrell Sweet.

I first encountered de Lint’s ‘Cerin’ character in the short story ‘A Pattern of Silver Strings’, which appeared in the anthology ‘The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories: 8’ (DAW Books, 1981). I found the story to be too insipid, and thus, I (skeptically) approached ‘The Harp of the Grey Rose’.

Surprisingly, ‘Harp’ actually is quite readable.

The prose style remains contrived in its effort to evoke the Fantasy Atmosphere: one character is named ‘Orion Starbreath’; another character is ‘prenticed’, not ‘apprenticed’. Elsewhere, ‘braying’ winds assault another character, and there are lots of hyphenated nouns designed to impart the tenor of Archaic English (‘truth-sayer’, ‘far-seer’, ‘wall-carvings’). To add to the triteness, our hero travels in the company of a telepathic bear (?!).

However, a crisp, quick-moving narrative, that contains surprises and revelations at the right places, overcomes these weaknesses and makes ‘Harp’ stand out.

As the novel opens, seventeen year-old Cerin Songweaver is contemplating what to do with his life. He is less than enthused about continuing to live in the small, closed-minded village in the West Downs where he grew up as an orphan, raised by the Wise Woman,Tess. Cerin has some skill at the harp, and one career choice is to travel to the city of Wistlore, and there be schooled by the finest of harpmasters.

However, one day while wandering the village green, Cerin meets a beautiful young woman with a grey rose in her hair. She is called, unsurprisingly….the Grey Rose.

Smitten, Cerin spends the Summer days in her company, discovering that this is a woman of........ melancholy mystery. The mystery dissipates at Summer’s end, when Cerin learns that the Grey Rose can no longer escape her destiny: as a member of the ancient race of the Tuathans, she is to be abducted, and deflowered (this is referred to in a vague manner), by a demon named Yarac.

The Grey Rose is by no means thrilled with this enterprise, but the sanctity of a bitterly earned, centuries-old truce rests upon her acquiescence. Cerin, however, is determined to rescue the Grey Rose from her fate. Alone, and armed with only his harp and a shortsword, our harpist sets out to cross the barren lands and dark woods of the wild to rescue his lady fair. In so doing, he will learn the truth of his own heritage, and of the role he will play in the coming clash between the forces of good and evil…..

As a fantasy novel, ‘Harp’ exhibits the sort of fast pacing and economy of plot that simply wouldn’t be feasible in today’s fantasy novels, where publishers mandate that novels be at least 500 pages long, and issued as a multi-volume set.

4 / 5 Stars

‘The Harp of the Grey Rose’ first was published in 1985; this Avon Books paperback (230 pp) was released in February, 1991, and features cover artwork by Darrell Sweet.

I first encountered de Lint’s ‘Cerin’ character in the short story ‘A Pattern of Silver Strings’, which appeared in the anthology ‘The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories: 8’ (DAW Books, 1981). I found the story to be too insipid, and thus, I (skeptically) approached ‘The Harp of the Grey Rose’.

Surprisingly, ‘Harp’ actually is quite readable.

The prose style remains contrived in its effort to evoke the Fantasy Atmosphere: one character is named ‘Orion Starbreath’; another character is ‘prenticed’, not ‘apprenticed’. Elsewhere, ‘braying’ winds assault another character, and there are lots of hyphenated nouns designed to impart the tenor of Archaic English (‘truth-sayer’, ‘far-seer’, ‘wall-carvings’). To add to the triteness, our hero travels in the company of a telepathic bear (?!).

However, a crisp, quick-moving narrative, that contains surprises and revelations at the right places, overcomes these weaknesses and makes ‘Harp’ stand out.

As the novel opens, seventeen year-old Cerin Songweaver is contemplating what to do with his life. He is less than enthused about continuing to live in the small, closed-minded village in the West Downs where he grew up as an orphan, raised by the Wise Woman,Tess. Cerin has some skill at the harp, and one career choice is to travel to the city of Wistlore, and there be schooled by the finest of harpmasters.

However, one day while wandering the village green, Cerin meets a beautiful young woman with a grey rose in her hair. She is called, unsurprisingly….the Grey Rose.

Smitten, Cerin spends the Summer days in her company, discovering that this is a woman of........ melancholy mystery. The mystery dissipates at Summer’s end, when Cerin learns that the Grey Rose can no longer escape her destiny: as a member of the ancient race of the Tuathans, she is to be abducted, and deflowered (this is referred to in a vague manner), by a demon named Yarac.

The Grey Rose is by no means thrilled with this enterprise, but the sanctity of a bitterly earned, centuries-old truce rests upon her acquiescence. Cerin, however, is determined to rescue the Grey Rose from her fate. Alone, and armed with only his harp and a shortsword, our harpist sets out to cross the barren lands and dark woods of the wild to rescue his lady fair. In so doing, he will learn the truth of his own heritage, and of the role he will play in the coming clash between the forces of good and evil…..

As a fantasy novel, ‘Harp’ exhibits the sort of fast pacing and economy of plot that simply wouldn’t be feasible in today’s fantasy novels, where publishers mandate that novels be at least 500 pages long, and issued as a multi-volume set.

As a main character Cerin is something of a milquetoast, and certainly no mightily-thewed man of action; readers should prepare for quite a bit of harp-playing in times of crisis, as opposed to flashing swords and dented bucklers. However, author de Lint uses varied locales, and an interesting cast of supporting characters, to make up for the lack of macho derring-do.

Whether you are a reader of 80s-style fantasy novels, or someone who is looking for a short- but entertaining - fantasy novel, ‘The Harp of the Grey Rose’ may be worth picking up.

Whether you are a reader of 80s-style fantasy novels, or someone who is looking for a short- but entertaining - fantasy novel, ‘The Harp of the Grey Rose’ may be worth picking up.

Labels:

The Harp of the Grey Rose

Saturday, October 11, 2014

H. P. Lovecraft by Michael Whelan

H. P. Lovecraft by Michael Whelan

As he relates in his book Michael Whelan's Works of Wonder (Del Rey, 1987), in the early 80s, Whelan attended a conference with Judy-Lynn Del Rey at the Del Rey / Ballantine offices to discuss cover artwork for the six volumes of H. P. Lovecraft novels and stories that were going to be issued in paperback. There, he learned that Del Rey was too cheap (my term, not Whelan's) to pay for cover art for all seven volumes. Instead, they had a budget for only two covers.

Whelan proposed making two large, panel-sized paintings, with each panel designed as a triptych. The individual book covers for the six mass-market paperbacks (published in 1981 - 1982) were derived from the triptychs.

The Del Rey trade paperback compilation, The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (1982), used the entire two panels for its wraparound cover.

As he relates in his book Michael Whelan's Works of Wonder (Del Rey, 1987), in the early 80s, Whelan attended a conference with Judy-Lynn Del Rey at the Del Rey / Ballantine offices to discuss cover artwork for the six volumes of H. P. Lovecraft novels and stories that were going to be issued in paperback. There, he learned that Del Rey was too cheap (my term, not Whelan's) to pay for cover art for all seven volumes. Instead, they had a budget for only two covers.

Whelan proposed making two large, panel-sized paintings, with each panel designed as a triptych. The individual book covers for the six mass-market paperbacks (published in 1981 - 1982) were derived from the triptychs.

The Del Rey trade paperback compilation, The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (1982), used the entire two panels for its wraparound cover.

For additional surveys of H. P. Lovecraft paperback cover art, readers are referred to recent postings at the Too Much Horror Fiction blog.

Wednesday, October 8, 2014

Heavy Metal magazine October 1984

'Heavy Metal' magazine October 1984

October, 1984, and in heavy rotation on the radio is 'No More Lonely Nights' by Paul McCartney. The song is the first single, and leadoff track, from McCartney's soundtrack to the film 'Give My Regards to Broad Street'. It features guitar work from Pink Floyd's David Gilmour.

The latest issue of 'Heavy Metal' magazine is out, with a front cover by Mark America, and a striking back cover by Tito Salmoni.

Given the mediocre nature of the August and September issues, this issue shows some much-needed improvement in its contents, primarily via the inclusion of standalone comics from veteran contributors Juan Gimenez ('A Matter of Time') and Caza ('Cinders').

Caza's 'Cinders' is particularly apt for October and Halloween, as it depicts the arrival of the Red Death to the city of the innocent, simpleton Homs......its grim nature is a departure from the more humorous outlook of his many comics for HM. But it shows that Caza could do horror stories that were as creepy, in their own unique way, as those of HM contributors Arthur Suydam or Jean Michel Nicolett.................

Labels:

Heavy Metal October 1984

Sunday, October 5, 2014

Book Review: The Year's Best Horror Stories: Series XV

Book Review: 'The Year's Best Horror Stories: XV' edited by Karl Edward Wagner

‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series XV’ (300 pp) is DAW Book No. UE2226 and was published in October, 1987. The nicely subversive cover artwork is by Michael Whelan, but unfortunately, it’s very small, due to the fact that starting with Series XIV, DAW began using a frame to enclose the illustrations on the front cover.

As with all the other volumes of ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories’, I approached this one with the expectation that perhaps 3 – 4 stories would be rewarding. All of the stories were published in 1986, some in small press magazines and anthologies, and others, in ‘slick’ magazines.

So, how does ‘Series XV’ stack up ? Well, needless to say, there are some good entries, but enough bad ones to justify giving this installment in the series a two-star rating.

Here are my brief summaries of the contents:

Introduction: Editor Wagner pontificates about the definition of horror, noting that "........schlock novels about giant maggots" qualify as ‘horror.’

He clearly was disdainful of authors like James Herbert, John Halkin, Guy Smith, and Shaun Hutson, who had no scruples about writing what could be considered 'schlock' novels, sometimes about carnivorous slugs, beetle larvae, reanimated aborted fetuses, etc. And of course, these writers never appeared in the DAW 'Year's Best' anthologies. However, I think all of them are great horror writers ! So much for Wagner’s pedantry…….

The Yougoslaves, by Robert Bloch: as he got older, Bloch’s writing could be hit-or-miss, but this tale qualifies as a Hit, and one of the better entries in the anthology. A tourist investigates gypsy-related crime among the Paris underworld.

Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back, by Joe R. Lansdale: Startlingly, Wagner lets a Splatterpunk tale sneak its way into the DAW anthologies.....! This story, about the aftermath of WW3, features unique monsters, and the kind of graphic horror that never would have appeared in previous editions of ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories’.

Apples, by Ramsey Campbell: UK tenement kids are rude to a neighbor and plunder his apple tree; this has consequences. One of Campbell’s more accessible tales, as - for some reason, and a not unwelcome one - he avoids the purpled prose that so afflicts his other short stories of this period.

Dead White Women, by William F. Wu: satirical tale of a man whose girlfriends never seem to stick around very long.

Crystal, by Charles L. Grant: A man buys a portrait; supernatural consequences ensue. Dull and unremarkable Grant story. Couldn't Karl Edward Wagner have found a story published somewhere.....anywhere ?!...... that better deserved to be in this anthology ?

Retirement, by Ron Leming: bikers, a roadside honkey-tonk, and a mysterious stranger. Competent, if not very original.

The Man Who Did Tricks With Glass, by Ron Wolfe: a man orders a special, mirror-filled room be made to his specifications. Author Wolfe apparently was trying to write a Charles Beaumont-style story; it doesn't work.

Bird in a Wrought Iron Cage, by John Alfred Taylor: short-short story, and one of the anthology’s better entries. A family heirloom gives its owner unique powers. But nothing comes without its price…..

The Olympic Runner, by Dennis Etchison: remarkably dull tale about mother – daughter conflict and psychological angst. Somehow, the 1984 Olympics get referenced. There is no horror content.

Take the ‘A’ Train, by Wayne Allen Sallee: a plotless follow-up to Sallee's plotless story in ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series XIV'…..

The Foggy, Foggy Dew, by Joel Lane: A Ramsey Campbell pastiche from admirer Lane. Whatever thin plot exists soon is smothered under empty sentences and unwieldy metaphors.

The Godmother, by Tina Rath: a young girl who goes to live in an English estate; the owner is particularly eccentric. Well-written, with a subtle Roald Dahl -ish vibe.

‘Pale, Trembling Youth’, by W. H. Pugmire and Jessica Amanda Salmonson: overwrought, corny tale about an older punk-rocker who observes youthful angst.

Red Light, by David J. Schow: a fashion model beset with psychological stress seeks assurance from her photographer boyfriend. Perhaps because it lacks the dark humor present in Schow’s better short stories, this one comes across as over-written and labored.

In the Hour Before Dawn, by Brad Strickland: unremarkable story about two men who encounter each other in their dreams. Yep, how's that for a gripping horror story premise ?

Necros, by Brian Lumley: an English tourist to the Italian coast meets a stunning young woman. Cuckolding her elderly husband may be the least of his problems……offbeat, entertaining tale from Lumley.

Tattoos, by Jack Dann: set in upstate New York, this story deals with a tattoo artist with a unique gift. Competently written, although the horror content is muted.

Acquiring a Family, by R. Chetwynd-Hayes: a spinster seeks company from supernatural sources. As with many of his short stories, this piece from Chetwynd-Hayes is well written, but doesn’t bring anything really new to the ghost story milieu.

The verdict ? The entries by Bloch, Lansdale, Taylor, and Lumley are the only real standouts in this particular volume. One can't help thinking that for ‘Series XV’, editor Wagner made at best a perfunctory effort at searching for, and finding, good stories. This volume is of interest only to those intent on collecting the whole series.

Friday, October 3, 2014

Iron Empires: Faith Conquers

Iron Empires: Faith Conquers

by Christopher Moeller

Dark Horse, February 2004

‘Iron Empires’ compiles four issues of the comic book

‘Shadow Empires: Faith Conquers’, which was published by Dark Horse from

August, 1994 to November, 1994.

It also contains ‘The Passage’, the inaugural Iron Empires comic, which first appeared as a black and white comic serialized in the Dark Horse Presents anthology. It has been colorized in this graphic novel.

Thematically and visually, IE:FC is similar to the Warhammer 40,000 aesthetic, and in fact, this graphic novel advertises the release of 'The Lost History of the Iron Empires' ruleset for a tabletop RPG, that apparently was based on the comic books, and was to be published in 2004, timed to join this Dark Horse graphic novel.

[Somewhat confusingly, it's not clear if the ruleset ever was indeed published; however, another incarnation of the Iron Empire RPG franchise, titled The Burning Empire, was published as a 656 page (!) rulebook in 2006 by Key 20 Publishing. ]

Trevor Faith is a 'Cotar Fomas', or warrior priest; his family, once eminent in faction politics, has fallen in status and favor, and Faith, by virtue of being a man of integrity and honor, is something of an outcast and troublemaker. As the novel opens, Faith has been dispatched to the frontier planet of Hotok, there to serve as the new chief officer of the Archbishop's guard.

Trevor Faith enlists the aid of Geil Carcajou, the Archbishop's attractive secretary - and his most loyal employee - in uncovering the conspiracy that underlies the fractious politics of Hotok.

As Trevor Faith soon discovers, there is a particularly troubling element to the conspiracy. For Hotok adjoins a vast region of space that has been infiltrated by a race of wormlike alien parasites: the Vaylen.

The Vaylen are capable of taking over the bodies of their human hosts, and forcing these hosts to do their bidding. And it looks like the cabal that is trying to overthrow the Archbishop may not have any scruples about using the Vaylen to render their adversaries into their puppets.

As Trevor Faith pursues the conspirators, events will take a dark and violent turn.....and the Kotar Fomas is on his own, thousands of light years from the nearest friendly outpost......

As a comic book series with a Space Opera flavor, IE:FC succeeds, although I can't endorse it as heartily as those quotes used in the back cover blurbs.

Moeller's artwork is the best thing about the book; reminiscent of Howard Chaykin in its use of color and panel composition, it also possesses a kinetic quality that is sometimes lacking in painted comic book artwork.

The writing, however, is where IE:FC labors. The backstory lacks sufficient exposition, and comes vaguely to light amid a confusing melange of invented proper nouns (there are the Dregutai...the Archotare....the Ravilar....the Stentor....the Corvus....mercator.....etc., etc.) and referential dialogue passages. Moeller seems to have been intent on adopting the 'Show, Don't Tell' philosophy of comic writing, and while such an approach may be warranted for some comics, for a galaxy-spanning space opera, well, exposition and orientation are 'musts'.

Keeping track of the various factions and characters becomes a bit wearisome as the narrative unfolds. While the book's narrative continually gains momentum in its final chapter, climaxing in a take-no-prisoners battle, at the finish of IE:FC I still had an incomplete understanding of what, exactly, the fighting was all about.......

'The Passage', the standalone story from Dark Horse Presents, is a self-contained tale of conscience awoken, and sheds a bit more light on the brutish nature of the religious wars that wrack the colonized worlds.

Summing up, IE:FC is a reasonably well-done space opera, if you are willing to overlook the obtuse nature of some of the plot. Moeller's artwork is a nice change from the line-art dominated, PC-centered, idiosyncratic aesthetic that dominates much of the contemporary lineup of sf graphic novels (Image's The Manhattan Projects comes to mind here).

Moeller released a sequel in 1998 – 1999 for DC Comic’s ‘Helix’ comic book imprint. The five-part ‘Sheva’s War’ also has been compiled into a graphic novel by Dark Horse, and released in 2004. I should have a review posted here at the PorPor Books Blog later this Fall.

by Christopher Moeller

Dark Horse, February 2004

It also contains ‘The Passage’, the inaugural Iron Empires comic, which first appeared as a black and white comic serialized in the Dark Horse Presents anthology. It has been colorized in this graphic novel.

Thematically and visually, IE:FC is similar to the Warhammer 40,000 aesthetic, and in fact, this graphic novel advertises the release of 'The Lost History of the Iron Empires' ruleset for a tabletop RPG, that apparently was based on the comic books, and was to be published in 2004, timed to join this Dark Horse graphic novel.

[Somewhat confusingly, it's not clear if the ruleset ever was indeed published; however, another incarnation of the Iron Empire RPG franchise, titled The Burning Empire, was published as a 656 page (!) rulebook in 2006 by Key 20 Publishing. ]

IE:FC is set in the far future, with the colonized worlds split into various politico-religious factions. These factions spend considerable effort in jockeying for primacy and attempting to subdue one another; charges of heresy are a worthwhile pretext for staging one atrocity after another.

The Archbishop, it seems, is a bit addled and senile, and a group of high-ranking clergy have taken advantage of his weakness and formed The Church of the Transition, a proxy meant to cover their actions to seize power for their own ends.

Trevor Faith enlists the aid of Geil Carcajou, the Archbishop's attractive secretary - and his most loyal employee - in uncovering the conspiracy that underlies the fractious politics of Hotok.

As Trevor Faith soon discovers, there is a particularly troubling element to the conspiracy. For Hotok adjoins a vast region of space that has been infiltrated by a race of wormlike alien parasites: the Vaylen.

The Vaylen are capable of taking over the bodies of their human hosts, and forcing these hosts to do their bidding. And it looks like the cabal that is trying to overthrow the Archbishop may not have any scruples about using the Vaylen to render their adversaries into their puppets.

As Trevor Faith pursues the conspirators, events will take a dark and violent turn.....and the Kotar Fomas is on his own, thousands of light years from the nearest friendly outpost......

As a comic book series with a Space Opera flavor, IE:FC succeeds, although I can't endorse it as heartily as those quotes used in the back cover blurbs.

Moeller's artwork is the best thing about the book; reminiscent of Howard Chaykin in its use of color and panel composition, it also possesses a kinetic quality that is sometimes lacking in painted comic book artwork.

The writing, however, is where IE:FC labors. The backstory lacks sufficient exposition, and comes vaguely to light amid a confusing melange of invented proper nouns (there are the Dregutai...the Archotare....the Ravilar....the Stentor....the Corvus....mercator.....etc., etc.) and referential dialogue passages. Moeller seems to have been intent on adopting the 'Show, Don't Tell' philosophy of comic writing, and while such an approach may be warranted for some comics, for a galaxy-spanning space opera, well, exposition and orientation are 'musts'.

Keeping track of the various factions and characters becomes a bit wearisome as the narrative unfolds. While the book's narrative continually gains momentum in its final chapter, climaxing in a take-no-prisoners battle, at the finish of IE:FC I still had an incomplete understanding of what, exactly, the fighting was all about.......

'The Passage', the standalone story from Dark Horse Presents, is a self-contained tale of conscience awoken, and sheds a bit more light on the brutish nature of the religious wars that wrack the colonized worlds.

Summing up, IE:FC is a reasonably well-done space opera, if you are willing to overlook the obtuse nature of some of the plot. Moeller's artwork is a nice change from the line-art dominated, PC-centered, idiosyncratic aesthetic that dominates much of the contemporary lineup of sf graphic novels (Image's The Manhattan Projects comes to mind here).

Moeller released a sequel in 1998 – 1999 for DC Comic’s ‘Helix’ comic book imprint. The five-part ‘Sheva’s War’ also has been compiled into a graphic novel by Dark Horse, and released in 2004. I should have a review posted here at the PorPor Books Blog later this Fall.

Labels:

Iron Empires: Faith Conquers

Monday, September 29, 2014

Book Review: Twistor

Book Review: 'Twistor' by John Cramer

3 / 5 Stars

‘Twistor’ first was published in 1989; this Avon Nova paperback version (338 pp) was released in November, 1991. The cover artwork is by Keith Parkinson.

In his Acknowledgement, author John Cramer indicates that the book was born from his observation that quality ‘hard’ sf was hard to find. In response, a friend challenged him to in fact write a hard sf novel, and thus, the result is ‘Twistor’.

The novel is set in Seattle, at the University of Washington Physics Department (where Cramer is, in real life, a faculty member in the department). In the laboratory of experimental physicist Alan Saxon, David Harrison, a postdoc, is working on a project to create a superconductor apparatus that exploits a (fictional) ‘holospin’ wave phenomenon derived from condensed matter physics.

If it works, the holospin superconductor will be capable of storing, and transmitting, large amounts of holographic data, revolutionizing computing and communications.

What David doesn’t know is that Saxon’s startup company is deeply in debt to the shady Megalith Corporation and its CEO, Martin Pierce. Saxon – not the most moral of individuals – is trying to wrinkle more money from Megalith by vaguely hinting at the potential financial rewards that could be unleashed if the holospin superconductor experiment proves valid.

Blinded by his own arrogance, Saxon doesn’t realize that Megalith is using all manner of clandestine actions to penetrate his subterfuges, and is on the verge of learning the true status of the work going on in the laboratory. Megalith’s goal: sell the secrets of the holospin superconductor to the world market.

Events take an unexpected turn when David Harrison conducts a late-night experiment and discovers that the superconductor field is capable of opening a portal, or ‘twistor’, to an alternate universe. Aided by the stunning, red-headed graduate student Vickie Gordon, Harrison redesigns his apparatus to expand the portal apparatus to sufficient size to accommodate human beings. But instead of embarking on a carefully prepared and executed mission, circumstances see Harrison forced through the portal, and into a strange parallel Earth.

Even as Victoria and the other graduate students and staff in the Physics Department struggle to figure out what has happened to David, Megalith makes its own move to acquire the twistor technology. And the corporation is quite willing to using violence to achieve its ends.....

‘Twistor’ succeeds as a hard sf novel. Like another hard sf novel, Benford’s ‘Timescape’ (1980), the details of actually dealing with the nuts and bolts of experimental physics are clearly communicated: David Harrison and Victoria Gordon don't stand around in white lab coats inside a gleaming,movie-set-style laboratory where a small army of hired help does all the dirty work to the rows of high-tech massive instruments, leaving the physicists to manipulate a control console and utter learned remarks.

Rather, the postdocs and grad students spend much of their time tinkering and troubleshooting their home-built contraptions. They are are part electrical engineers, part programmers, part machinists, part electricians, and, arching over all these trades and tasks, physicists. Cramer makes clear that in academia, building an apparatus and getting it to work is only a part of the larger scheme of dealing with the need to apply for, and obtain, funding to support all the activities that take place in the laboratory.

‘Twistor’ does have its weaknesses. The book is too long by about 30 – 40 pages; better editing would have seen the elimination of a cutesy sub-plot, involving a fairy tale, that serves more as filler than a vital component of the narrative.

There also are too many passages that awkwardly explore the personal interactions among the main characters; one gets the impression that the author was advised to include these in an effort to inject ‘human interest’ into the novel, lest it become a predictably dry recitation of scientific activities. And the novel closes by invoking the standard-issue trope that only Knowledge Shared can liberate Humanity from its conflicts and close-mindedness; a less Pollyanna-ish attitude would have lent the book the darker, grittier edge it needs to really stand out.

If you’re a fan of hard sf, or if you’re someone who remembers doing experimental physics research back in the day when MacSE computers, VAX terminals, and BitNet were new and exciting, then ‘Twistor’ is worth picking up.

3 / 5 Stars

‘Twistor’ first was published in 1989; this Avon Nova paperback version (338 pp) was released in November, 1991. The cover artwork is by Keith Parkinson.

In his Acknowledgement, author John Cramer indicates that the book was born from his observation that quality ‘hard’ sf was hard to find. In response, a friend challenged him to in fact write a hard sf novel, and thus, the result is ‘Twistor’.

The novel is set in Seattle, at the University of Washington Physics Department (where Cramer is, in real life, a faculty member in the department). In the laboratory of experimental physicist Alan Saxon, David Harrison, a postdoc, is working on a project to create a superconductor apparatus that exploits a (fictional) ‘holospin’ wave phenomenon derived from condensed matter physics.

If it works, the holospin superconductor will be capable of storing, and transmitting, large amounts of holographic data, revolutionizing computing and communications.

What David doesn’t know is that Saxon’s startup company is deeply in debt to the shady Megalith Corporation and its CEO, Martin Pierce. Saxon – not the most moral of individuals – is trying to wrinkle more money from Megalith by vaguely hinting at the potential financial rewards that could be unleashed if the holospin superconductor experiment proves valid.

Blinded by his own arrogance, Saxon doesn’t realize that Megalith is using all manner of clandestine actions to penetrate his subterfuges, and is on the verge of learning the true status of the work going on in the laboratory. Megalith’s goal: sell the secrets of the holospin superconductor to the world market.

Events take an unexpected turn when David Harrison conducts a late-night experiment and discovers that the superconductor field is capable of opening a portal, or ‘twistor’, to an alternate universe. Aided by the stunning, red-headed graduate student Vickie Gordon, Harrison redesigns his apparatus to expand the portal apparatus to sufficient size to accommodate human beings. But instead of embarking on a carefully prepared and executed mission, circumstances see Harrison forced through the portal, and into a strange parallel Earth.

Even as Victoria and the other graduate students and staff in the Physics Department struggle to figure out what has happened to David, Megalith makes its own move to acquire the twistor technology. And the corporation is quite willing to using violence to achieve its ends.....

‘Twistor’ succeeds as a hard sf novel. Like another hard sf novel, Benford’s ‘Timescape’ (1980), the details of actually dealing with the nuts and bolts of experimental physics are clearly communicated: David Harrison and Victoria Gordon don't stand around in white lab coats inside a gleaming,movie-set-style laboratory where a small army of hired help does all the dirty work to the rows of high-tech massive instruments, leaving the physicists to manipulate a control console and utter learned remarks.

Rather, the postdocs and grad students spend much of their time tinkering and troubleshooting their home-built contraptions. They are are part electrical engineers, part programmers, part machinists, part electricians, and, arching over all these trades and tasks, physicists. Cramer makes clear that in academia, building an apparatus and getting it to work is only a part of the larger scheme of dealing with the need to apply for, and obtain, funding to support all the activities that take place in the laboratory.

‘Twistor’ does have its weaknesses. The book is too long by about 30 – 40 pages; better editing would have seen the elimination of a cutesy sub-plot, involving a fairy tale, that serves more as filler than a vital component of the narrative.

There also are too many passages that awkwardly explore the personal interactions among the main characters; one gets the impression that the author was advised to include these in an effort to inject ‘human interest’ into the novel, lest it become a predictably dry recitation of scientific activities. And the novel closes by invoking the standard-issue trope that only Knowledge Shared can liberate Humanity from its conflicts and close-mindedness; a less Pollyanna-ish attitude would have lent the book the darker, grittier edge it needs to really stand out.

If you’re a fan of hard sf, or if you’re someone who remembers doing experimental physics research back in the day when MacSE computers, VAX terminals, and BitNet were new and exciting, then ‘Twistor’ is worth picking up.

Labels:

Twistor

Friday, September 26, 2014

The Black Terror by Smith, Dixon, and Brereton

The Black Terror

Beau Smith, Chuck Dixon, Dan Brereton

Eclipse Comics, 1990

'The Black Terror' was a costumed crime-fighter who first appeared in 1941 in Exciting Comics; since that time, the rights to the character have passed through a seemingly endless number of indie comics companies. The most recent incarnation of the character is in a webcomic titled 'Curse of the Black Terror'.

In 1990 indie publisher Eclipse Comics acquired the rights to the character, part of the company's strategy of issuing superhero titles based on Golden Age properties, such as Airboy.

'The Black Terror' appeared as a three-issue prestige format series during October, 1989 (issue 1), March, 1990 (issue 2) and June, 1990 (issue 3).

Beau Smith, Chuck Dixon, Dan Brereton

Eclipse Comics, 1990

'The Black Terror' was a costumed crime-fighter who first appeared in 1941 in Exciting Comics; since that time, the rights to the character have passed through a seemingly endless number of indie comics companies. The most recent incarnation of the character is in a webcomic titled 'Curse of the Black Terror'.

In 1990 indie publisher Eclipse Comics acquired the rights to the character, part of the company's strategy of issuing superhero titles based on Golden Age properties, such as Airboy.

'The Black Terror' appeared as a three-issue prestige format series during October, 1989 (issue 1), March, 1990 (issue 2) and June, 1990 (issue 3).

The Eclipse Comics series was written by Beau Smith and Chuck Dixon. The artist, who supplied painted artwork, was Dan Brereton.'The Black Terror' was his first major comic book assignment. Brereton has since gone on to be one of most well-known contemporary comic book artists, one of the more celebrated examples of his work being DC's Thrillkiller.

In the Eclipse Comics series, the Black Terror is one Ryan Delvecchio, who is working as hired muscle for a Chicago crime syndicate headed by Anthony Capone, descendent of Al Capone.

Capone has corrupted the entire political establishment of Illinois (remember, these were the days before Rod Blagojevich), and the clandestine crime-fighting organization that Delvecchio works for is convinced that Capone has ambitions to take control of the economy of the entire country.

By day, Delvecchio works alongside Frankie Dio, the psychopathic enforcer for the Capone family. Together, he and Dio track down and punish squealers and embezzlers who have earned the wrath of the Capone family. At night, donning the garb of The Black Terror, Delvecchio rousts criminals and sleazeballs, grilling them in the hope of uncovering Capone's plans.

'The Black Terror' is first and foremost a crime comic rather than a superhero comic; the focus is on mood and atmosphere and a (rather incoherent) plot. On the whole, Brereton's artwork, relying heavily on blacks, grays, and splashes of incongruous color, works best in this sort of milieu. The few fight scenes that occupy the trilogy tend to come across as static and inert.

In keeping with the dedicated Noir atmosphere of 'The Black Terror', there is a femme fatale in the form of Anthony Capone's daughter Allison. Brereton ably represents her as a sort of quasi-Goth chick, in an early 90s style......

If you are a fan of Brereton's artwork, or a fan of crime comics with a 'retro', Noir-ish aesthetic, then 'The Black Terror' is worth getting. While a graphic novel compiling the three-issue series has never been released, full sets of the all three comics can be obtained for reasonable prices at your usual dealers.

Labels:

The Black Terror

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)