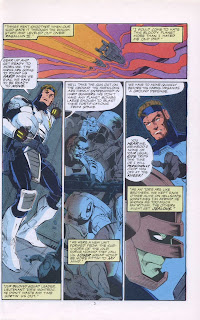

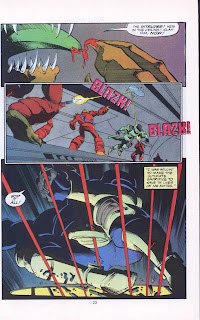

Alien Legion: The Ditch

by Chuck Dixon (writer) and Larry Stroman (art)

Alien Legion No. 5, June 1988

Epic / Marvel

Alien Legion was launched by Marvel's Epic Comics imprint in 1984, with The Alien Legion issues 1 - 20 released in 1984 - 1987. Eighteen issues of a second series, somewhat confusingly titled simply Alien Legion, was released during 1987 - 1990.

One of the more entertaining characters in the Legion - which creator Carl Potts envisioned as 'the Foreign Legion in space' - was Jugger Grimrod, a genuine 'grunt' perpetually in danger of being booted out for insubordination.

In this standalone tale from issue 5 of the second series, Grimrod finds himself alone and abandoned on a hostile planet.......the consequence of yet another screwup by the High Command. But, aided by plentiful amounts of mud and blood, Grimrod finds a way to overcome all obstacles and complete the mission. It's fast-moving adventure, with lots of sarcastic humor, and good artwork by Larry Stroman.

Thursday, April 21, 2016

Sunday, April 17, 2016

Book Review: The Truth About Chernobyl

Book Review: 'The Truth About Chenobyl' by Grigori Medvedev

3 / 5 Stars

I remember when I first heard about the disaster at Chernobyl: it was on Tuesday, April 29, 1986. I was a graduate student at Louisiana State University at the time, and I was sitting in the barber shop in the Student Union, and a morning news program - I forget which one - was playing on the television mounted on the wall of the shop. The anchor announced that an accident had occurred at a nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union.

The coverage of the Chernobyl accident being broadcast on the televisions and newspapers in the United States was limited, and mainly comprised of rumor; this was back before there was an internet, or Twitter, or Facebook, and it was much easier for the Soviet government to hide the scope of the disaster. But it was quite obvious that something disastrous had happened in the Soviet Union, and as more details began to emerge over the following weeks, it became clear that the world's worst nuclear disaster had taken place.

On the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, I thought I would read one of the first books that addressed the phenomenon: Grigori Medvedev's The Truth About Chernobyl, which first was published in 1989 in Russia, followed by this English language translation (274 pp.; Basic Books) which was released in 1991.

The capsule summary: early in the morning of April 26, 1986, there was a catastrophic explosion of Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant at Pripyat, Ukraine (then a part of the Soviet Union). The accident led to the release of massive amounts of radioactive particulates (400 times more than that of the Hiroshima atomic bomb detonation) into the atmosphere, with fallout covering large areas of western and northern Europe.

The plant managers initially refused to believe that the reactor had been destroyed, and told the Soviet authorities in Moscow that the plant had suffered minor damage from a turbine explosion. It wasn't until the afternoon of April 27 that the authorities began the evacuation of the entire population (approximately 50,000 people) from Pripyat.

(an excellent photoessay on the disaster is available here)

Only the self-sacrificial actions of engineers and firefighters prevented the reactor from undergoing additional, even more disastrous, explosions. Using a labor force of a quarter of a million workers, by November 1986 a concrete 'sarcophagous' was erected over the ruins of the reactor. A massive effort to collect and bury radioactive debris and soil from the areas surrounding Pripyat continued into 1987. Ukrainian officials have declared that the area around Chenobyl will not be safe for human habitation for another 20,000 years.

Grigori Medvedev was a nuclear engineer who, in 1986, was working at the Soviet government's 'Suyuzatomenergostroy' national energy directorate. Medvedev had worked at a number of nuclear power plants in the USSR, including a stint as a deputy chief engineer at Chernobyl in the 1970s; he even had been hospitalized for radiation sickness (for an exposure that he does not detail). In May, 1986, he was sent by his management to Chernobyl to investigate the situation and report back. Much of the book's contents are derived from his observations and analysis associated with that investigation.

At the time the book was published in 1989, the Soviet government had refused to release to the public the complete truth of its investigations into the causes of the accident; this despite the emphasis on 'glasnost' by the Gorbachev presidency. So much of Medvedev's book is devoted - sometimes in an oblique way - to condemning the Soviet system, which in 1989 was a risky action even for a well-regarded engineer and subject matter expert like himself.

The first 50 pages of 'The Truth About Chernobyl' are devoted to excoriating the Chernobyl plant bureaucrats who overlooked safety problems, and ordered the ill-advised experiment that led to the reactor explosion.

These bureaucrats (Viktor Bryukhanov, Nikolai Fomin, and Anatoly Dyatlov) had little experience in the operation of nuclear power plants and were placed in positions of seniority mainly through political connection (which of course included membership in the Communist Party) rather than technical expertise.

Medvedev also has little respect for the Soviet bureaucracy that supervised the construction and operation of nuclear power plants across the country, many of which had secret histories of accidents and near-disasters, the result of design flaws in the reactors and shoddy construction.

The narrative then moves to a highly technical overview of the reactor's operation and the actions that led to the explosion; this is weakest part of the book, as Medvedev makes little effort to make his prose accessible to the layman. The presence of explanatory diagrams, charts, or schematics would have made reading this section much easier, but they are absent.

Where the book is strongest is in its chronological account of the actions taken after the explosion, on up to the second week in May, when Medvedev left the area to return to Moscow. These accounts provide insight into the confusion and disbelief, as well as the stupidity of many senior bureaucrats and officials, that exacerbated the severity of the situation.

One of the weaknesses of The Truth About Chernobyl is that it fails to cover the events after the first week of May, at which time Medvedev returned to Moscow.....thus, readers must consult other books for the epic tale of the thousands of 'liquidators' and construction personnel who cleaned up the area in the vicinity of the reactor and constructed the massive sarcophagous that entombs it to this day.

Summing up: while The Truth About Chernobyl lacks the insights of books written at a later time point post-disaster, when more information had become available, it remains one of the more important accounts of the accident and its immediate aftermath.

3 / 5 Stars

I remember when I first heard about the disaster at Chernobyl: it was on Tuesday, April 29, 1986. I was a graduate student at Louisiana State University at the time, and I was sitting in the barber shop in the Student Union, and a morning news program - I forget which one - was playing on the television mounted on the wall of the shop. The anchor announced that an accident had occurred at a nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union.

The coverage of the Chernobyl accident being broadcast on the televisions and newspapers in the United States was limited, and mainly comprised of rumor; this was back before there was an internet, or Twitter, or Facebook, and it was much easier for the Soviet government to hide the scope of the disaster. But it was quite obvious that something disastrous had happened in the Soviet Union, and as more details began to emerge over the following weeks, it became clear that the world's worst nuclear disaster had taken place.

On the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, I thought I would read one of the first books that addressed the phenomenon: Grigori Medvedev's The Truth About Chernobyl, which first was published in 1989 in Russia, followed by this English language translation (274 pp.; Basic Books) which was released in 1991.

The capsule summary: early in the morning of April 26, 1986, there was a catastrophic explosion of Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant at Pripyat, Ukraine (then a part of the Soviet Union). The accident led to the release of massive amounts of radioactive particulates (400 times more than that of the Hiroshima atomic bomb detonation) into the atmosphere, with fallout covering large areas of western and northern Europe.

The plant managers initially refused to believe that the reactor had been destroyed, and told the Soviet authorities in Moscow that the plant had suffered minor damage from a turbine explosion. It wasn't until the afternoon of April 27 that the authorities began the evacuation of the entire population (approximately 50,000 people) from Pripyat.

(an excellent photoessay on the disaster is available here)

Only the self-sacrificial actions of engineers and firefighters prevented the reactor from undergoing additional, even more disastrous, explosions. Using a labor force of a quarter of a million workers, by November 1986 a concrete 'sarcophagous' was erected over the ruins of the reactor. A massive effort to collect and bury radioactive debris and soil from the areas surrounding Pripyat continued into 1987. Ukrainian officials have declared that the area around Chenobyl will not be safe for human habitation for another 20,000 years.

Grigori Medvedev was a nuclear engineer who, in 1986, was working at the Soviet government's 'Suyuzatomenergostroy' national energy directorate. Medvedev had worked at a number of nuclear power plants in the USSR, including a stint as a deputy chief engineer at Chernobyl in the 1970s; he even had been hospitalized for radiation sickness (for an exposure that he does not detail). In May, 1986, he was sent by his management to Chernobyl to investigate the situation and report back. Much of the book's contents are derived from his observations and analysis associated with that investigation.

At the time the book was published in 1989, the Soviet government had refused to release to the public the complete truth of its investigations into the causes of the accident; this despite the emphasis on 'glasnost' by the Gorbachev presidency. So much of Medvedev's book is devoted - sometimes in an oblique way - to condemning the Soviet system, which in 1989 was a risky action even for a well-regarded engineer and subject matter expert like himself.

The first 50 pages of 'The Truth About Chernobyl' are devoted to excoriating the Chernobyl plant bureaucrats who overlooked safety problems, and ordered the ill-advised experiment that led to the reactor explosion.

These bureaucrats (Viktor Bryukhanov, Nikolai Fomin, and Anatoly Dyatlov) had little experience in the operation of nuclear power plants and were placed in positions of seniority mainly through political connection (which of course included membership in the Communist Party) rather than technical expertise.

Medvedev also has little respect for the Soviet bureaucracy that supervised the construction and operation of nuclear power plants across the country, many of which had secret histories of accidents and near-disasters, the result of design flaws in the reactors and shoddy construction.

The narrative then moves to a highly technical overview of the reactor's operation and the actions that led to the explosion; this is weakest part of the book, as Medvedev makes little effort to make his prose accessible to the layman. The presence of explanatory diagrams, charts, or schematics would have made reading this section much easier, but they are absent.

Where the book is strongest is in its chronological account of the actions taken after the explosion, on up to the second week in May, when Medvedev left the area to return to Moscow. These accounts provide insight into the confusion and disbelief, as well as the stupidity of many senior bureaucrats and officials, that exacerbated the severity of the situation.

Medvedev also presents a chapter on the fate of the workers and firemen who were transferred to Clinic No. 6 in Moscow for treatment of acute radiation exposure; the details of how many of these individuals succumbed are graphic and unsettling, and Medvedev uses these details to underscore the toll that the ineptitude and negligence of the Soviet system extracted from its citizens.

Summing up: while The Truth About Chernobyl lacks the insights of books written at a later time point post-disaster, when more information had become available, it remains one of the more important accounts of the accident and its immediate aftermath.

Labels:

The Truth About Chernobyl

Thursday, April 14, 2016

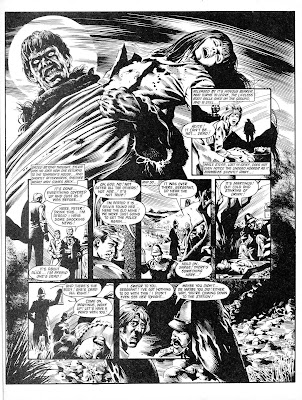

Plague of the Zombies

Plague of the Zombies

by Steve Moore (script) and Brian Bolland (art)

from House of Hammer, No. 13 (October 1977)

During its short, two-year lifespan (1976 - 1978), the 23 issues of Dez Skinn's House of Hammer black-and-white magazine emerged as something more than just a British version of the American publication Famous Monsters of Filmland.

It is true that most of the content of House of Hammer consisted of articles about horror movies, copiously illustrated with stills, as did Famous Monsters. But House of Hammer also ran in each issue a black-and-white comics adaptation of a Hammer film. These comics (which were usually 15 or so pages in length) could only offer a truncated, condensed retelling of the film, often with too much panel space devoted to dialogue and exposition. But they featured outstanding artwork from a number of talented British artists who, in the 80s and 90s, would go on to become stars for their contributions to flagship titles for Marvel and DC.

I've posted below the comics adaption of the 1966 Hammer film Plague of the Zombies. The movie was rather tame by today's standards - there is more blood and gore in a single minute of each episode of The Walking Dead - but the artwork by Brian Bolland is top-notch, featuring some excellent stippling, cross-hatching, and shading effects, artistic work that is rarely seen in contemporary U. S. comics of any genre.

by Steve Moore (script) and Brian Bolland (art)

from House of Hammer, No. 13 (October 1977)

During its short, two-year lifespan (1976 - 1978), the 23 issues of Dez Skinn's House of Hammer black-and-white magazine emerged as something more than just a British version of the American publication Famous Monsters of Filmland.

It is true that most of the content of House of Hammer consisted of articles about horror movies, copiously illustrated with stills, as did Famous Monsters. But House of Hammer also ran in each issue a black-and-white comics adaptation of a Hammer film. These comics (which were usually 15 or so pages in length) could only offer a truncated, condensed retelling of the film, often with too much panel space devoted to dialogue and exposition. But they featured outstanding artwork from a number of talented British artists who, in the 80s and 90s, would go on to become stars for their contributions to flagship titles for Marvel and DC.

I've posted below the comics adaption of the 1966 Hammer film Plague of the Zombies. The movie was rather tame by today's standards - there is more blood and gore in a single minute of each episode of The Walking Dead - but the artwork by Brian Bolland is top-notch, featuring some excellent stippling, cross-hatching, and shading effects, artistic work that is rarely seen in contemporary U. S. comics of any genre.

Labels:

Plague of the Zombies

Monday, April 11, 2016

Book Review: The Shadow of the Ship

Book Review: 'The Shadow of the Ship' by Robert Wilfred Franson

‘The Shadow of the Ship’ ( 273 pp) was published by Del Rey Books in May, 1983 ; the cover illustration is by David B. Mattingly.

I got about half-way through the book before giving up in exasperation…….it’s not a very good novel.

It certainly has an interesting premise: among the 54 habitable planets comprising the Nation, interplanetary travel is accomplished not by spaceships, but by ground transport using specialized wormholes called ‘trails’: extra-dimensional tracks through hyperspace.

These trails – which are perhaps of alien origin - can be hundreds, perhaps thousands of miles in length; the habitable and uninhabitable planets of the Nation lie along the trails like beads on a string.

Travelling these various trails requires the use of self-contained, pressurized cars, which are linked like a train, and pulled by unique, elephant-like animals called waybeasts. The extra-dimensional space within which the trails lie is airless vacuum; its dangers are severe, for anyone or anything that moves too far outside the narrow boundaries of the trail can be instantly disintegrated by cosmic forces unknown.

The hero of ‘Shadow’ is a man named Hendrik Eiverdein Rheinallt. ‘Eiverdein’, as he is called, is sponsoring a unique caravan expedition into the farther reaches of the Blue Trail, where, it is rumored, a spaceship has been seen. Everdein’s ambition is to recover the spaceship, and use it to return to his long-lost homeland of Earth.

The narrative centers on the long journey of the caravan, and various political and personal intrigues and conspiracies of its passengers – for there are those in the Nation who would not like to see interplanetary or interstellar travel replace the profitable caravan routes.

‘Shadow’ was the first novel of author Franson, and it has the self-consciously ‘literary’ attitude of many first novels: it is intent on displaying the author’s skills as an artisan of written prose, rather than telling a good story.

Much of the writing and the dialogue have a stilted quality, as well as the use of a lot of empty words and phrases, as this example shows:

“Men exploiting the appearance of violent strength come from safe lands where a shove or a punch is the worst physical results; so violent gestures and attitudes are meaningless except as intimidation or insults.”

Rheinallt grinned. “You wish to apply this dichotomy to me rather than to yourself ? Remember that not all weapons are as visible as an axe.”

“Correct; there is also organization. Come, Eiverdein: from what sort of place do you hail ?”

“A cloud-soft land; but there were violent elements.”

Here’s a remark from a floating cat-like alien (?!) named Arahant:

“Perhaps that lack of kinship is what saved my aural channels from overload at Whitecloud. A selective deafness to overbearing shrillness is scarcely vulgar. It’s essential to be able to close one’s ears to high-altitude winds; all the Luftmenschen know that. Besides, I wouldn’t be able to understand the structural nuances of my own operas if – “

Here’s an example of what can politely be called ‘wooden’ exposition:

Late on the next Clockday Rheinallt was sitting at his desk, feeling bewebbed in the hassles of administering a caravan en route. Glenavet, he thought, was more or less neutralized by the death of his active associate, the delegate Wirtellin. Rheinallt did not expect him to cease his advocacy among the caravaneers, but tentatively had pegged him as a basic trailhand: honest enough, not imaginative, and not unnecessarily violent.

To make matters worse, when someone aboard the caravan dies as a result of foul play, it's an excuse for the author to insert a blank-verse poems, under the pretext of having a Bard sing the travelers a funeral dirge.........here's a couple of verses:

1 / 5 Stars

I got about half-way through the book before giving up in exasperation…….it’s not a very good novel.

It certainly has an interesting premise: among the 54 habitable planets comprising the Nation, interplanetary travel is accomplished not by spaceships, but by ground transport using specialized wormholes called ‘trails’: extra-dimensional tracks through hyperspace.

These trails – which are perhaps of alien origin - can be hundreds, perhaps thousands of miles in length; the habitable and uninhabitable planets of the Nation lie along the trails like beads on a string.

Travelling these various trails requires the use of self-contained, pressurized cars, which are linked like a train, and pulled by unique, elephant-like animals called waybeasts. The extra-dimensional space within which the trails lie is airless vacuum; its dangers are severe, for anyone or anything that moves too far outside the narrow boundaries of the trail can be instantly disintegrated by cosmic forces unknown.

The hero of ‘Shadow’ is a man named Hendrik Eiverdein Rheinallt. ‘Eiverdein’, as he is called, is sponsoring a unique caravan expedition into the farther reaches of the Blue Trail, where, it is rumored, a spaceship has been seen. Everdein’s ambition is to recover the spaceship, and use it to return to his long-lost homeland of Earth.

The narrative centers on the long journey of the caravan, and various political and personal intrigues and conspiracies of its passengers – for there are those in the Nation who would not like to see interplanetary or interstellar travel replace the profitable caravan routes.

‘Shadow’ was the first novel of author Franson, and it has the self-consciously ‘literary’ attitude of many first novels: it is intent on displaying the author’s skills as an artisan of written prose, rather than telling a good story.

Much of the writing and the dialogue have a stilted quality, as well as the use of a lot of empty words and phrases, as this example shows:

“Men exploiting the appearance of violent strength come from safe lands where a shove or a punch is the worst physical results; so violent gestures and attitudes are meaningless except as intimidation or insults.”

Rheinallt grinned. “You wish to apply this dichotomy to me rather than to yourself ? Remember that not all weapons are as visible as an axe.”

“Correct; there is also organization. Come, Eiverdein: from what sort of place do you hail ?”

“A cloud-soft land; but there were violent elements.”

Here’s a remark from a floating cat-like alien (?!) named Arahant:

“Perhaps that lack of kinship is what saved my aural channels from overload at Whitecloud. A selective deafness to overbearing shrillness is scarcely vulgar. It’s essential to be able to close one’s ears to high-altitude winds; all the Luftmenschen know that. Besides, I wouldn’t be able to understand the structural nuances of my own operas if – “

Here’s an example of what can politely be called ‘wooden’ exposition:

Late on the next Clockday Rheinallt was sitting at his desk, feeling bewebbed in the hassles of administering a caravan en route. Glenavet, he thought, was more or less neutralized by the death of his active associate, the delegate Wirtellin. Rheinallt did not expect him to cease his advocacy among the caravaneers, but tentatively had pegged him as a basic trailhand: honest enough, not imaginative, and not unnecessarily violent.

To make matters worse, when someone aboard the caravan dies as a result of foul play, it's an excuse for the author to insert a blank-verse poems, under the pretext of having a Bard sing the travelers a funeral dirge.........here's a couple of verses:

Whistle down the darkened plain

Where the silent vacuum shrieks

Like Time's hungry wind alone

...

Some are leaping up to vanish

Where a fear of edge of death

Can't flatter life to bribe a foothold

To matter where there is none

So long the chord is gone

...

Some are rushing home to nothing

Where they're turning off their mind

To chatter brightly like a person

And batter down their echoed soul

And empty hiss like steam

The verdict ? With better editing, this could have been a worthy first novel, but as it stands, 'The Shadow of the Ship' is best avoided.

Labels:

The Shadow of the Ship

Friday, April 8, 2016

The Egg by Potter

The Egg

by J. K. Potter and Tim Caldwell

from Epic Illustrated No. 7, August 1981

One of the more memorable entries in Heavy Metal magazine in the late 70s was the photo-based comic titled 'The Doll' by J. K. Potter, which was published in the September, 1979 issue.

Potter's work - which relied on manual alterations to photographs, this done in the days before Photoshop - did not lend itself to high output, but in 1981 he did produce another creepy work, this one titled 'The Egg', for Marvel's Epic Illustrated.

I've posted it below.

by J. K. Potter and Tim Caldwell

from Epic Illustrated No. 7, August 1981

One of the more memorable entries in Heavy Metal magazine in the late 70s was the photo-based comic titled 'The Doll' by J. K. Potter, which was published in the September, 1979 issue.

Potter's work - which relied on manual alterations to photographs, this done in the days before Photoshop - did not lend itself to high output, but in 1981 he did produce another creepy work, this one titled 'The Egg', for Marvel's Epic Illustrated.

I've posted it below.

Labels:

The Egg by Potter

Tuesday, April 5, 2016

Book Review: Seeklight

Book Review: 'Seeklight' by K. W. Jeter

4 / 5 Stars

When his first novel, 1972’s ‘Dr. Adder’, was rejected by publishers, K. W. Jeter resigned himself to writing a more conventional sf novel – one without explicit sex and violence, or cyberpunk stylings.

4 / 5 Stars

When his first novel, 1972’s ‘Dr. Adder’, was rejected by publishers, K. W. Jeter resigned himself to writing a more conventional sf novel – one without explicit sex and violence, or cyberpunk stylings.

This second novel was called ‘Seeklight’, and he submitted it to Laser Books, a sf imprint founded by Canadian romance novel publisher Harlequin Books.

Although Laser Books had editorial policies that were considered restrictive as far as sf publishing in the New Wave era was concerned, it also was willing to publish and promote new authors, and in due course, ‘Seeklight’ (192 pp; Laser Book No. 7) was published in 1975, with cover art by Kelly Freas.

(In 1976, Jeter published a second novel with Laser Books, ‘The Dreamfields’.)

In his Introduction, Laser Books editor Barry Maltzberg declared ‘Seeklight’ to be one of the best sf novels he had ever read by an author new to the field.

And ‘Seeklight’ is indeed a good ‘debut’ novel. In some ways, it’s better than ‘Dr. Adder’ (which finally saw print in 1984).

‘Seeklight’ is set on an un-named colony planet where society adheres to a feudal paradigm. Some advanced technologies, such as giant transport vehicles, robots, and computers, still are functioning centuries after planetfall, but these machines constantly are breaking down and being abandoned, as the knowledge to repair them is being lost.

The protagonist, a boy named Daenek, lives with his mother on the hills above the quarry that employs most of the local workforce. Daenek is disliked by the people of the neighboring village, who denounce him for being ‘the Thane’s Son’. His mother, a woman of aristocratic bearing slowly losing her health to deep depression, refuses to divulge the reasons for the villagers' antipathy.

Daenek grows up with an awareness that he is of a more high-born lineage than the small-minded, mean-spirited villagers. His origins remain a mystery, however, and what little knowledge he can gain of life in the far-off Capitol – his possible birthplace - are gleaned from his conversations with an itinerant quarry-worker named Stepke.

On the eve of his 18th birthday, events take a sudden and dangerous turn, and Daenek finds himself a hunted outcast. He embarks upon a search for the headquarters of the Regent, the Thane’s successor, and in so doing, learns the truth underlying the fate of the Thane……and what it means for the future of the planet………

‘Seeklight’ is a character-driven novel with a clear, uncontrived prose style – one that is generated, to some extent, by the editorial stance of the Laser Books imprint. I found it reminiscent of the novels of British sf authors of the 70s like Michael Coney (Rax) and Richard Cowper (The Road to Corlay) in its reserved tone and deliberate pacing. Like the novels of Coney and Cowper, ‘Seeklight’ closes with a revelation, one that is understated and ambiguous.

‘Seeklight’ also is original in its treatment of entropy –very much an ‘in’ topic during the New Wave era, and one that was becoming increasingly over-exposed in the sf of the 70s. I won’t disclose any spoilers, except to say that Jeter indicates that simply recognizing that a civilization is in the grip of entropy is a difficult and hazardous task.

Summing up, ‘Seeklight’ is a one of the more readable debut novels of the New Wave era, due to its clear prose and compact length. This one is worth picking up.

Although Laser Books had editorial policies that were considered restrictive as far as sf publishing in the New Wave era was concerned, it also was willing to publish and promote new authors, and in due course, ‘Seeklight’ (192 pp; Laser Book No. 7) was published in 1975, with cover art by Kelly Freas.

(In 1976, Jeter published a second novel with Laser Books, ‘The Dreamfields’.)

In his Introduction, Laser Books editor Barry Maltzberg declared ‘Seeklight’ to be one of the best sf novels he had ever read by an author new to the field.

And ‘Seeklight’ is indeed a good ‘debut’ novel. In some ways, it’s better than ‘Dr. Adder’ (which finally saw print in 1984).

‘Seeklight’ is set on an un-named colony planet where society adheres to a feudal paradigm. Some advanced technologies, such as giant transport vehicles, robots, and computers, still are functioning centuries after planetfall, but these machines constantly are breaking down and being abandoned, as the knowledge to repair them is being lost.

The protagonist, a boy named Daenek, lives with his mother on the hills above the quarry that employs most of the local workforce. Daenek is disliked by the people of the neighboring village, who denounce him for being ‘the Thane’s Son’. His mother, a woman of aristocratic bearing slowly losing her health to deep depression, refuses to divulge the reasons for the villagers' antipathy.

Daenek grows up with an awareness that he is of a more high-born lineage than the small-minded, mean-spirited villagers. His origins remain a mystery, however, and what little knowledge he can gain of life in the far-off Capitol – his possible birthplace - are gleaned from his conversations with an itinerant quarry-worker named Stepke.

On the eve of his 18th birthday, events take a sudden and dangerous turn, and Daenek finds himself a hunted outcast. He embarks upon a search for the headquarters of the Regent, the Thane’s successor, and in so doing, learns the truth underlying the fate of the Thane……and what it means for the future of the planet………

‘Seeklight’ is a character-driven novel with a clear, uncontrived prose style – one that is generated, to some extent, by the editorial stance of the Laser Books imprint. I found it reminiscent of the novels of British sf authors of the 70s like Michael Coney (Rax) and Richard Cowper (The Road to Corlay) in its reserved tone and deliberate pacing. Like the novels of Coney and Cowper, ‘Seeklight’ closes with a revelation, one that is understated and ambiguous.

‘Seeklight’ also is original in its treatment of entropy –very much an ‘in’ topic during the New Wave era, and one that was becoming increasingly over-exposed in the sf of the 70s. I won’t disclose any spoilers, except to say that Jeter indicates that simply recognizing that a civilization is in the grip of entropy is a difficult and hazardous task.

Summing up, ‘Seeklight’ is a one of the more readable debut novels of the New Wave era, due to its clear prose and compact length. This one is worth picking up.

Labels:

Seeklight

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)