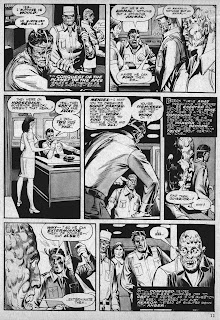

Battle for the Planet of the Apes

Parts III and IV of VII

by Doug Moench (script) and Sonny Trinidad, Yong Montano, and Dino Castrillo (art)

Planet of the Apes (Marvel / Curtis) No. 25, October 1976

The entirety of this issue of the magazine was devoted to continuing the 'Battle' adaption....a team of three artists was recruited to handle the art chores.

Both Yong Montano and Dino Castrillo were Filipino artists, who did a variety of work for Marvel in the mid-70s.

I have posted Part III below.

Part One is here.

Part Two is here.

Part Four is here.

Part Five is here.

Part Six is here.

Monday, September 19, 2016

Friday, September 16, 2016

Book Review: Nebula Award Stories Number Two

Book Review: Nebula Award Stories Number Two

edited by Brian Aldiss and Harry Harrison

3 / 5 Stars

‘Nebula Award Stories Number 2’ (244 pp) by published by Pocket Books in September 1968. The cover artwork is by Jack Gaughan.

This anthology contains novelettes and short stories published in 1966, all of which either were selected for Nebula Awards, or placed on the 'Roll of Honor'. Thus, this collection is as good an example of the New Wave movement in its ascendancy as any of the era, including Ellison’s Dangerous Visions anthology from 1967.

In a smug Afterword titled ‘The Year in SF’, editors Aldiss and Harrison have a great deal of fun mocking the majority of entries in the sf magazines of 1966……..pulp-minded stories wedded to outdated notions of sf, stories that (in one of their more bizarre phrases) ‘annihilate thinking’....?!

The digests that publish these stories are ‘living on intellectually unearned income, cannibalizing their past’.

In the minds of Aldiss and Harrison, it is the job of the SFWA to identify and promote genre works that have Literary Merit. In so doing, the SFWA will aid people in ‘….better understanding …..the dynamically changing world about them.’

Needless to say, my goal here at the PorPor Books Blog is to examine New Wave era works with a more critical eye than they received when first they appeared in those giddy days of the mid-60s. Accordingly, here are my capsule reviews of the entries in ‘Nebula Award Stories Number Two’.............

The Secret Place, by Richard McKenna: the Nebula Award 1966 winner for Best Short Story from the by-then deceased author of The Sand Pebbles. The plot deals with an Army officer searching for uranium deposits in an Oregon desert during the waning years of the Second World War. A troubled young woman from a nearby village may provide aid.

It’s easy to see why Aldiss and Harrison and the SFWA selected this story for receipt of a Nebula Award. Its sf content is muted, even absent; with its emphasis on the emotional and psychological states of the characters, it could easily have been printed in any number of general fiction magazines still on the shelves in 1966, such as The Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, or The New Yorker.

But when read 50 years later, it’s the type of story that elicits – at best – a shrug. Bob Shaw's story (below) certainly was more worthy of the Nebula Award than 'The Secret Place'.

Light of Other Days, by Bob Shaw: this has since become a classic of 60s sf. It does a good job of combining the human element – in this case, marital conflicts – with an sf concept, in this case, a special kind of window that replays events from the past.

Who Needs Insurance ? by Robin S. Scott: Pete ‘Ace’ Albers, crewman and pilot aboard WW2 and Viet Nam war planes and choppers, is blessed with what seem to be unusually good luck………the kind of luck that raises suspicions……….. Combining a fast-moving, humorous prose style with sf elements, this story holds up very well when read 50 years later.

Among the Hairy Earthmen, by R. A. Lafferty: unconvincing fable about the Gods of Greek Mythology influencing human affairs.

The Last Castle, by Jack Vance: another classic of 60s sf. A novelette about Earth in the far-future, where a society of lotus-eating aristocrats faces extinction at the hands of rebellious alien laborers. Needless to say, this novelette reads as well now as it did 50 years ago.

Day Million, by Frederik Pohl: in the far future, sex and romance will have very different - even shocking - meanings then they do today. For this short story, Pohl has his first-person narrator relate the story in a 60s 'hip' vernacular: Cripes man, take my word for it. The result is painfully awkward and unconvincing.

When I Was Miss Dow, by Sonya Dorman: an alien race that can assume any form – and any gender – they deem convenient assigns one of their number to befriend a visiting Terran. A contemporary critic would undoubtedly praise this tale for its use of sf to explore Gender Roles and the Nature of Human Emotions. Be that as it may, this story is nothing special.

Call Him Lord, by Gordon R. Dickson: the arrogant prince of an intergalactic empire must make a social call to the archaic planet Earth. Another of the better stories in the anthology.

In the Imagicon, by George Henry Smith: Dandor relies on his virtual reality console, the Imagicon, to achieve the ultimate in escapism. This entertaining short-short story features satiric humor and, in its denouement, a clever twist.

We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, by Philip K. Dick: the classic Dick story, and the basis for the 1990 film Total Recall. Howevermuch Dick has been praised for his imaginative approach to sf, this story demonstrates that as a prose stylist, he was not much better than the pulp writers that editors Aldiss and Harrison mock in their Afterward. There is awkward syntax.... wooden dialogue........ and characters who don’t speak, but Grate, in this tale………..

Man in His Time, by Brian Aldiss: editor Harrison, in the Introduction to this story, assures the reader that his fellow editor Aldiss didn’t know that this story was being selected for the anthology, thus – presumably – deterring accusations of editorial favoritism.

The story starts with an astronaut, returned from a Mars journey, talking to the thin air, and exhibiting other eccentricities. His wife and psychiatrist are trying to cope. After several pages go by, Aldiss reveals that the astronaut has been infected, so to speak, with the ability to perceive events 3.3 minutes in advance of everyone else on Earth.

It's an interesting concept, but unfortunately, Aldiss neglects to adequately frame the physics of this phenomenon, preferring instead to focus on the emotional and psychological interactions of the astronaut and his wife. This gives the story an obtuse quality. Although Harrison declares that this tale says ‘something vital ……about the human condition’, in my opinion, it’s a real Dud.

Summing up, ‘Nebula Award Stories Number 2’ has a sufficient quota of rewarding stories to make it worth getting.

edited by Brian Aldiss and Harry Harrison

3 / 5 Stars

‘Nebula Award Stories Number 2’ (244 pp) by published by Pocket Books in September 1968. The cover artwork is by Jack Gaughan.

This anthology contains novelettes and short stories published in 1966, all of which either were selected for Nebula Awards, or placed on the 'Roll of Honor'. Thus, this collection is as good an example of the New Wave movement in its ascendancy as any of the era, including Ellison’s Dangerous Visions anthology from 1967.

In a smug Afterword titled ‘The Year in SF’, editors Aldiss and Harrison have a great deal of fun mocking the majority of entries in the sf magazines of 1966……..pulp-minded stories wedded to outdated notions of sf, stories that (in one of their more bizarre phrases) ‘annihilate thinking’....?!

The digests that publish these stories are ‘living on intellectually unearned income, cannibalizing their past’.

In the minds of Aldiss and Harrison, it is the job of the SFWA to identify and promote genre works that have Literary Merit. In so doing, the SFWA will aid people in ‘….better understanding …..the dynamically changing world about them.’

Needless to say, my goal here at the PorPor Books Blog is to examine New Wave era works with a more critical eye than they received when first they appeared in those giddy days of the mid-60s. Accordingly, here are my capsule reviews of the entries in ‘Nebula Award Stories Number Two’.............

The Secret Place, by Richard McKenna: the Nebula Award 1966 winner for Best Short Story from the by-then deceased author of The Sand Pebbles. The plot deals with an Army officer searching for uranium deposits in an Oregon desert during the waning years of the Second World War. A troubled young woman from a nearby village may provide aid.

It’s easy to see why Aldiss and Harrison and the SFWA selected this story for receipt of a Nebula Award. Its sf content is muted, even absent; with its emphasis on the emotional and psychological states of the characters, it could easily have been printed in any number of general fiction magazines still on the shelves in 1966, such as The Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, or The New Yorker.

But when read 50 years later, it’s the type of story that elicits – at best – a shrug. Bob Shaw's story (below) certainly was more worthy of the Nebula Award than 'The Secret Place'.

Light of Other Days, by Bob Shaw: this has since become a classic of 60s sf. It does a good job of combining the human element – in this case, marital conflicts – with an sf concept, in this case, a special kind of window that replays events from the past.

Who Needs Insurance ? by Robin S. Scott: Pete ‘Ace’ Albers, crewman and pilot aboard WW2 and Viet Nam war planes and choppers, is blessed with what seem to be unusually good luck………the kind of luck that raises suspicions……….. Combining a fast-moving, humorous prose style with sf elements, this story holds up very well when read 50 years later.

Among the Hairy Earthmen, by R. A. Lafferty: unconvincing fable about the Gods of Greek Mythology influencing human affairs.

The Last Castle, by Jack Vance: another classic of 60s sf. A novelette about Earth in the far-future, where a society of lotus-eating aristocrats faces extinction at the hands of rebellious alien laborers. Needless to say, this novelette reads as well now as it did 50 years ago.

Day Million, by Frederik Pohl: in the far future, sex and romance will have very different - even shocking - meanings then they do today. For this short story, Pohl has his first-person narrator relate the story in a 60s 'hip' vernacular: Cripes man, take my word for it. The result is painfully awkward and unconvincing.

When I Was Miss Dow, by Sonya Dorman: an alien race that can assume any form – and any gender – they deem convenient assigns one of their number to befriend a visiting Terran. A contemporary critic would undoubtedly praise this tale for its use of sf to explore Gender Roles and the Nature of Human Emotions. Be that as it may, this story is nothing special.

Call Him Lord, by Gordon R. Dickson: the arrogant prince of an intergalactic empire must make a social call to the archaic planet Earth. Another of the better stories in the anthology.

In the Imagicon, by George Henry Smith: Dandor relies on his virtual reality console, the Imagicon, to achieve the ultimate in escapism. This entertaining short-short story features satiric humor and, in its denouement, a clever twist.

We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, by Philip K. Dick: the classic Dick story, and the basis for the 1990 film Total Recall. Howevermuch Dick has been praised for his imaginative approach to sf, this story demonstrates that as a prose stylist, he was not much better than the pulp writers that editors Aldiss and Harrison mock in their Afterward. There is awkward syntax.... wooden dialogue........ and characters who don’t speak, but Grate, in this tale………..

Man in His Time, by Brian Aldiss: editor Harrison, in the Introduction to this story, assures the reader that his fellow editor Aldiss didn’t know that this story was being selected for the anthology, thus – presumably – deterring accusations of editorial favoritism.

The story starts with an astronaut, returned from a Mars journey, talking to the thin air, and exhibiting other eccentricities. His wife and psychiatrist are trying to cope. After several pages go by, Aldiss reveals that the astronaut has been infected, so to speak, with the ability to perceive events 3.3 minutes in advance of everyone else on Earth.

It's an interesting concept, but unfortunately, Aldiss neglects to adequately frame the physics of this phenomenon, preferring instead to focus on the emotional and psychological interactions of the astronaut and his wife. This gives the story an obtuse quality. Although Harrison declares that this tale says ‘something vital ……about the human condition’, in my opinion, it’s a real Dud.

Summing up, ‘Nebula Award Stories Number 2’ has a sufficient quota of rewarding stories to make it worth getting.

Labels:

Nebula Award Stories Number Two

Monday, September 12, 2016

Heavy Metal magazine Fall 1986

'Heavy Metal' magazine Fall 1986

It's September, 1986, and the Fall issue of Heavy Metal magazine is released. The cover illustration is by Enki Bilal.On MTV and on FM radio, the song 'Captain of Her Heart', by the Swiss duo Double, is in rotation. It's not easy for a band with a French name whose song is getting airplay in the US; I remember listening to the radio at the time and hearing one US deejay pronounce the group as 'double', not doo-BLAY.......

Most of the content of the Fall 1986 issue is made up of a mediocre Bilal entry titled 'Trapped Women'. But there still is some life in the magazine yet; the best entry in this issue is a graphically violent, offbeat, post-apocalyptic cannibal tale by Jose Ortiz: 'Please Don't Feed the Animals'.

It's September, 1986, and the Fall issue of Heavy Metal magazine is released. The cover illustration is by Enki Bilal.On MTV and on FM radio, the song 'Captain of Her Heart', by the Swiss duo Double, is in rotation. It's not easy for a band with a French name whose song is getting airplay in the US; I remember listening to the radio at the time and hearing one US deejay pronounce the group as 'double', not doo-BLAY.......

Labels:

Heavy Metal magazine Fall 1986

Saturday, September 10, 2016

Visions: the Art of Arthur Suydam

Visions: The Art of Arthur Suydam

Dark Horse Books, February 1994

'Visions' (128 pp) is a sturdy chunk of an art book, measuring 12 " x 12" and printing on quality paper stock.

[It's too big to fit on my scanner bed, so I can only provide excerpts of its pages]

If you were a dedicated Heavy Metal reader during its early years (i.e. 1977 - 1980), then you know that Arthur Suydam (pr. Soo-DAM) was an integral part of the artistic landscape of that magazine. Strips like 'Food for the Children', 'Lulea', and 'Mama's Place' remain as memorable nowadays as they did back then.

During the 80s, Suydam's contributions expanded to Epic Illustrated and its comic book line, where he published his 'Cholly and Flytrap' series. Suydam also contributed to Neal Adam's Continuity Comics.

Starting in the early 90s, Suydam became a standout cover artist for a variety of publishers, among them Dark Horse comics, whose series 'Aliens: Genocide' featured dramatic color paintings by Suydam.

On into the 2000s, Suydam became associated with the covers for the best-selling Marvel Zombies imprint. He is a major draw at comics conventions, although some of his appearances at these functions have elicited controversy from other presenters..........?! Not being an attendee at Comic Cons myself, and thus not entirely understanding the atmosphere at such places, I refrain from interjecting any editorial comments of my own.

'Visions' Suydam's artwork up till 1992. Its four chapters cover Paintings, Children's Books, Drawings, and Comics.

'Paintings' provides color reproductions of Suydam's art for the Dark Horse 'Aliens: Genocide' and 'Aliens 3' series, as well as covers he produced for Continuity Comics and DC.

'Children's Books' deals with color and black and white illustrations Suydam was commissioned to create in 1988 for editions of The Wind in the Willows and Brer Rabbit by Kipling Press. (While the Brer Rabbit book apparently was published, I had difficulty finding a record of The Wind in the Willows book ever being issued).

The chapter on 'Drawings' is the briefest in the book and offers up some pen-and-ink studies of barbarians and nubile women.

The final chapter, 'Comics', is the best in the book, providing full-page and half-page reproductions of selected panels from Suydam's work on 'Mudwogs' and 'Cholly and Flytrap'. The meticulous craftsmanship that defines Suydam's approach to illustration is evident when looking at these enlarged panels.

The only weakness in 'Visions: The Art of Arthur Suydam' is the narrative, written by Franz Henkel. While this narrative does offer some small bits of information about when and where the presented artwork appeared, most of it consists of pretentious exposition, using a prose style better suited to academic journals than an art book.

Dark Horse Books, February 1994

'Visions' (128 pp) is a sturdy chunk of an art book, measuring 12 " x 12" and printing on quality paper stock.

[It's too big to fit on my scanner bed, so I can only provide excerpts of its pages]

If you were a dedicated Heavy Metal reader during its early years (i.e. 1977 - 1980), then you know that Arthur Suydam (pr. Soo-DAM) was an integral part of the artistic landscape of that magazine. Strips like 'Food for the Children', 'Lulea', and 'Mama's Place' remain as memorable nowadays as they did back then.

During the 80s, Suydam's contributions expanded to Epic Illustrated and its comic book line, where he published his 'Cholly and Flytrap' series. Suydam also contributed to Neal Adam's Continuity Comics.

Starting in the early 90s, Suydam became a standout cover artist for a variety of publishers, among them Dark Horse comics, whose series 'Aliens: Genocide' featured dramatic color paintings by Suydam.

On into the 2000s, Suydam became associated with the covers for the best-selling Marvel Zombies imprint. He is a major draw at comics conventions, although some of his appearances at these functions have elicited controversy from other presenters..........?! Not being an attendee at Comic Cons myself, and thus not entirely understanding the atmosphere at such places, I refrain from interjecting any editorial comments of my own.

'Visions' Suydam's artwork up till 1992. Its four chapters cover Paintings, Children's Books, Drawings, and Comics.

'Paintings' provides color reproductions of Suydam's art for the Dark Horse 'Aliens: Genocide' and 'Aliens 3' series, as well as covers he produced for Continuity Comics and DC.

'Children's Books' deals with color and black and white illustrations Suydam was commissioned to create in 1988 for editions of The Wind in the Willows and Brer Rabbit by Kipling Press. (While the Brer Rabbit book apparently was published, I had difficulty finding a record of The Wind in the Willows book ever being issued).

The chapter on 'Drawings' is the briefest in the book and offers up some pen-and-ink studies of barbarians and nubile women.

The final chapter, 'Comics', is the best in the book, providing full-page and half-page reproductions of selected panels from Suydam's work on 'Mudwogs' and 'Cholly and Flytrap'. The meticulous craftsmanship that defines Suydam's approach to illustration is evident when looking at these enlarged panels.

For example, in the text below, second-to-last sentence, Henkel uses the word 'bricoleur'; according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, this word is:

one who putters about, from the French bricoler

Another weakness of 'Visions' is that it doesn't provide any information about Suydam's technique. Usually an art overview of this type gives at least some details about how the artist creates his compositions. Whether the absence of such information in 'Visions' is the result of a decision by Suydam to keep his artistic techniques to himself, or a decision by the book's creators to avoid any mention of techniques, is unclear.

[I should mention the other Suydam art book that has been published to date: The Fantastic Art of Arthur Suydam, released by Vanguard in 2005. I haven't read this book, but it gets mixed reviews at amazon.]

Summing up, whether you are a Suydam fan, or someone who appreciates modern American illustration, then 'Visions: The Art of Arthur Suydam' may be worth picking up. The book's large format and high quality reproductions are definite pluses, as well as the fact that used copies in good condition are available for under $20.

[I should mention the other Suydam art book that has been published to date: The Fantastic Art of Arthur Suydam, released by Vanguard in 2005. I haven't read this book, but it gets mixed reviews at amazon.]

Summing up, whether you are a Suydam fan, or someone who appreciates modern American illustration, then 'Visions: The Art of Arthur Suydam' may be worth picking up. The book's large format and high quality reproductions are definite pluses, as well as the fact that used copies in good condition are available for under $20.

Wednesday, September 7, 2016

Book Review: Damnation Alley

Book Review: 'Damnation Alley' by Roger Zelazny

5 / 5 Stars

‘Damnation Alley’ first appeared in 1967 in Galaxy digest as a novella; Zelazny later expanded it into a novel for publication in 1969. This Berkley Books paperback (157 pp), with a cover illustration by Paul Lehr, was released in June, 1970.

I remember reading the novel back when it first came out and finding it something of a novelty…..and a welcome novelty, at that. For in 1970 the New Wave movement was well emplaced in sf, and straightforward adventure novels like ‘Damnation Alley’ were rare.

The novel was of course made into a 1977 movie which is not regarded as one of the finest moments in sf cinema. But 47 years after it was first published, the novel still is engaging and readable.

The plot is straightforward: 100 years or so following World War Three, most of the interior of the USA is a wasteland populated by mutated animals – including gila monsters the size of small trucks. Zones of radiation left from nuke detonations mean certain death for those who lack the necessary shielding. The atmosphere has been altered, and storms of lethal ferocity regularly scour the landscapes, rendering air travel impossible.

An outbreak of bubonic plague in Boston threatens to depopulate the entire city; the only hope of succor is the depots of ‘Haffikine antiserum’ in the possession of Los Angeles. An ex-Hells Angel and ex-felon, with the appropriate name of Hell Tanner, is offered a deal: a Pardon for all of his offences, provided he delivers the antiserum to Boston – by driving across the country on the route known as Damnation Alley.

No one ever has made the complete Alley drive and survived. But Tanner is equipped with the latest in technology: a Super Car with eight all-terrain wheels, automated viewscreens, and a pleasing arsenal of rockets, machine guns, and flamethrowers.

Hell Tanner sets out on the Alley run…….but in case he decides to change his mind and break for freedom rather than Boston, two other cars are travelling right behind him……….with orders to kill Tanner the moment he tries to deviate from his mission…..

Although Zelazny may have considered ‘Damnation Alley’ as a less ‘artistic’ novel than his other works of the time, looking back on it from nearly 50 years later, it arguably broke new ground in the adventure novel genre. Its use of an antihero represents a break from the standard sf traditions of the time. The setting of a diseased and blasted landscape, filled with perpetual dangers, remains imaginative.

5 / 5 Stars

‘Damnation Alley’ first appeared in 1967 in Galaxy digest as a novella; Zelazny later expanded it into a novel for publication in 1969. This Berkley Books paperback (157 pp), with a cover illustration by Paul Lehr, was released in June, 1970.

I remember reading the novel back when it first came out and finding it something of a novelty…..and a welcome novelty, at that. For in 1970 the New Wave movement was well emplaced in sf, and straightforward adventure novels like ‘Damnation Alley’ were rare.

The novel was of course made into a 1977 movie which is not regarded as one of the finest moments in sf cinema. But 47 years after it was first published, the novel still is engaging and readable.

The plot is straightforward: 100 years or so following World War Three, most of the interior of the USA is a wasteland populated by mutated animals – including gila monsters the size of small trucks. Zones of radiation left from nuke detonations mean certain death for those who lack the necessary shielding. The atmosphere has been altered, and storms of lethal ferocity regularly scour the landscapes, rendering air travel impossible.

An outbreak of bubonic plague in Boston threatens to depopulate the entire city; the only hope of succor is the depots of ‘Haffikine antiserum’ in the possession of Los Angeles. An ex-Hells Angel and ex-felon, with the appropriate name of Hell Tanner, is offered a deal: a Pardon for all of his offences, provided he delivers the antiserum to Boston – by driving across the country on the route known as Damnation Alley.

No one ever has made the complete Alley drive and survived. But Tanner is equipped with the latest in technology: a Super Car with eight all-terrain wheels, automated viewscreens, and a pleasing arsenal of rockets, machine guns, and flamethrowers.

Hell Tanner sets out on the Alley run…….but in case he decides to change his mind and break for freedom rather than Boston, two other cars are travelling right behind him……….with orders to kill Tanner the moment he tries to deviate from his mission…..

Although Zelazny may have considered ‘Damnation Alley’ as a less ‘artistic’ novel than his other works of the time, looking back on it from nearly 50 years later, it arguably broke new ground in the adventure novel genre. Its use of an antihero represents a break from the standard sf traditions of the time. The setting of a diseased and blasted landscape, filled with perpetual dangers, remains imaginative.

Zelazny’s openly cynical approach to the aftermath of the Apocalypse, one that refuses to adopt the standard humanistic approach of self-salvation arising from the ashes, was influential in sci-fi culture. For example, in 1978, 2000 AD magazine ran a lengthy Judge Dredd story, 'The Cursed Earth', that was heavily influenced by 'Damnation', although it worked in passages of mordant humor that quite were lacking in Zelazny's novel.

That’s not to say that ‘Damnation’ is a perfect novel. Zelazny couldn’t quite resist the urge to insert several New Wave prose segments into his novel. These take the form of prose poems, some of which are two pages on length, and are barely coherent. I can’t imagine any modern-day readers responding well to these affectations.

Still, when all is said and done, in my opinion, ‘Damnation Alley’ remains one of the best sf novels to be published in the 1960s, and, along with Jack of Shadows, one of Zelazny’s better works.

That’s not to say that ‘Damnation’ is a perfect novel. Zelazny couldn’t quite resist the urge to insert several New Wave prose segments into his novel. These take the form of prose poems, some of which are two pages on length, and are barely coherent. I can’t imagine any modern-day readers responding well to these affectations.

Still, when all is said and done, in my opinion, ‘Damnation Alley’ remains one of the best sf novels to be published in the 1960s, and, along with Jack of Shadows, one of Zelazny’s better works.

Labels:

Damnation Alley

Saturday, September 3, 2016

Once Upon A Time

Once Upon A Time

edited by David Larkin

Bantam/Peacock Press, September 1976

'Once Upon A Time' was published in September 1976 by Bantam Books under its Peacock Press imprint, which specialized in trade paperbacks devoted to art and illustration. The editor of the Peacock Press was David Larkin.

Although Bantam discontinued the Peacock Press line in 1977, Larkin had continued success in working with other publishers, releasing a number of well-received illustrated fantasy books such as Faeries (1978), Giants (1980) and Castles (1984).

edited by David Larkin

Bantam/Peacock Press, September 1976

Although Bantam discontinued the Peacock Press line in 1977, Larkin had continued success in working with other publishers, releasing a number of well-received illustrated fantasy books such as Faeries (1978), Giants (1980) and Castles (1984).

The Forgotten Temple by Alan Lee

'Once Upon A Time' is a collection of 44 plates, all composed from 1975 - 1976, on fantasy and folklore themes. Most of the featured artists are British, and, with the exception of Ian Miller, most of them were not well known outside their field.

Of all the illustrations in the book, only Pauline Ellisons' paintings for the Bantam Book paperback editions of Leguin's A Wizard of Earthsea are likely to be recognized by modern readers.

Earthsea Trilogy (panel) by Pauline Ellison

To be fair, while most of the entries in 'Once Upon A Time' have the simplistic style associated with illustrations for children's books (or in some cases imitate the styles of 19th century artists such as Arthur Rackham), in 1976, children's books were the only real market for what we now consider 'fantasy' art.

Daffy Daggles by Chris McEwan

It's also important to remember that back in the mid 70s, abstract art dominated the curricula at art schools. Realistic art, including illustration, was considered outmoded, and few (if any) faculty were willing to provide instruction in the subject. Those students who sought training in realistic art often had to fend for themselves; when it came to trying to earn a living providing such art to commercial markets, the situation was even more difficult.

The Sword of Thrac (unpublished illustration) by Brian Froud

Nowadays, fantasy and sf fans take for granted that they can walk into any Barnes and Noble and see significant shelf space set aside for art collections such as the Spectrum series. But fifty years ago, back in 1976, you were lucky if your local Waldenbooks or Coles or Brentanos carried a Tolkien calendar or two......and maybe a Frank Frazetta calendar, too......and that was pretty much it for fantasy art books.

Lord of the Dragons (unpublished illustration) by Frank Bellamy

Summing up,'Once Upon A Time' is best regarded as a pioneering effort to bring fantasy art out of its status as a children's medium, and into some degree of acceptance as a legitimate artistic endeavor in its own right. By offering the public a reasonably priced collection of genre art, it paved the way for the success the field enjoys today.

The Dreaded Bombax Bird by Wayne Anderson

Painting for The Witch's Hat by Tony Meeuwissen

Painting for The Witch's Hat by Tony Meeuwissen

Labels:

Once Upon A Time

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)