Book Review: 'Darkover Landfall' by Marion Zimmer Bradley

While I was growing up in the 70s I never paid much attention to the ‘Darkover’ SF novels by Marion Zimmer Bradley.

When I did try and read one of her books, it was 1982’s Arthurian treatment ‘The Mists of Avalon’, which was so remarkably boring that I decided to never again try a Bradley novel.

The passage of time mellows sworn vows, however, so I decided that since I’m looking over a lot of the DAW books from the 70s, I might as well give a ‘Darkover’ entry a try.

When I did try and read one of her books, it was 1982’s Arthurian treatment ‘The Mists of Avalon’, which was so remarkably boring that I decided to never again try a Bradley novel.

The passage of time mellows sworn vows, however, so I decided that since I’m looking over a lot of the DAW books from the 70s, I might as well give a ‘Darkover’ entry a try.

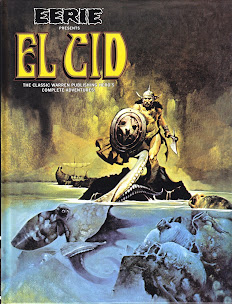

Starting with ‘The Planet Savers’ in 1958, to her death in 1999, Bradley produced nearly 40 Darkover novels, some in collaboration with other writers, and some released posthumously. ‘Darkover Landfall’ (DAW Books No. 36, December 1972, cover art by Jack Gaughan, 160 pp.) is technically the first volume in the series, as it describes the advent of humans to the planet Darkover.

The story opens with a spaceship – originally destined for the colony world of Coronis - crash-landed on Darkover; many of the crew have perished in the impact, and the dazed survivors are struggling to erect tents and procure food and water while their vehicle is evaluated for repairs.

Fortunately the atmosphere and chemistry of Darover is compatible with human biology, but the ship’s captain has no idea as to where in the galaxy their emergency landing site is located. Rafael MacAran, the ship’s geologist, is recruited to journey to a nearby mountain to erect instruments capable of analyzing the night-time constellations and other planetary data.

The weather on Darkover is tumultuous, changing from sunshine, to rain, to sleet, and snow, all in the course of a day. Luckily the ship’s crew includes a group of colonists of Scottish descent, whose ancestors lived in the Hebrides and the Orkney Islands. Accustomed to perpetual rain, sleet, snow, overcast skies, and other manifestations of wretched weather, these stalwarts cope by drinking whiskey, dancing, and singing Ballads from the Olde Country.

However, just as the crash survivors are starting to assess the likelihood of lifting off into space again, the 'Ghost Wind' takes them unawares. Will madness seize the colonists and destroy their chances of ever leaving Darkover ? Are there indigenous life-forms on the planet, and are they hostile ? Will discord among the survivors lead to internecine warfare and doom any chance at escape ?

.jpg)