The Sacred and the Profane

by Dean Motter (plot) and Ken Steacy (art)

Graphic Novel, Eclipse Books, 1987

The Sacred and the Profane first appeared as a five-part series in the black and white indie comic Star*Reach in 1977 - 1978. Archie Goodwin later approached the creators about publishing a revised, colorized version of the series in Epic Illustrated. The new series was launched in the October, 1983 issue and continued through the October, 1984 issue.

This 1987 Eclipse Books graphic novel compiles all of the Epic Illustrated episodes, as well as a sketchbook section, commentary by the authors, and an Introduction by Archie Goodwin.

The premise of the story is that in 2043, the SETI array receives a transmission from space, a transmission that suggests the presence of intelligent life in the Andromeda galaxy. A few years later, the Vatican announces that it is converting most of its assets to fund a small fleet of spaceships. Their goal: travel to the Andromeda galaxy, and proselytize to whatever aliens are responsible for sending the transmission.

Carrying a mixed crew of 215 clergy, nuns, and laypeople, in 2047, the St. Catherine sets off on its fateful journey to the stars.

Even before the St. Catherine has reached the region of space thought to contain the transmission's point of origin, there is dissent and argument in the ranks, fueled by both personal and philosophical intrigues.

But when the St Catherine does indeed encounter the alien life-form, all internal struggles must be set aside....for the alien does not appear to be friendly, and the ship soon is invaded.....and the lives of the entire crew put at risk.

Will the peaceful acquiescence recommended by the clergy be enough to deter the aliens ? Or is the violent response advocated by the secular members of the crew the more effective path ? Either way, time is running out aboard the St Catherine......and soon it will be too late for anyone to have any hope of survival....

Unfortunately, TSATP is best regarded as a comic book concept whose reach exceeded its grasp...........

Writer Motter seeks to infuse the storyline with 'deep' questions about spirituality, organized religion, self-identity, the Validity of the Other, etc., etc. As a result, the plot is overwhelmed by having too many passages of dialogue in which various characters berate, argue, remonstrate, debate, and cavil at one another.

The aliens - which are never really given much in the way of substance or explanation - serve a simple function as a sort of 'cosmic' Rorschach Blot upon which the crew of the St. Catherine project their existential angst and emotional insecurities.

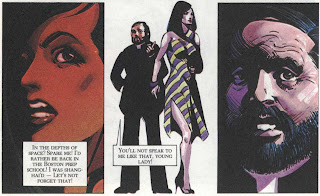

A pretentious storyline can sometmes be salvaged by great artwork, and at first glimpse, Steacy's artwork seems to accomplish this. It has a distinctive style, calling to mind the melding of art deco with medieval, stained-glass imagery.

The problem is, the comic book / graphic novel printing technology of the 80s could not really accommodate this style, and as a result, the artwork looks murky and underexposed, making it difficult for the reader to figure out what, exactly, is taking place among the crew of the St. Catherine.

Steacy's artwork also suffers from being static in terms of its presentation; blocky and underlit, the action sequences lack the 'traditional' comic book visual enhancements - such as speed lines, impact bursts, and sound effects - that would impart a necessary degree of dynamism to the depicted activities.

As well, the fact that much of the narrative revolves around scenes of conversations means that, with the exception of some brief, Star Wars - derived spaceship battles that take place early on in the story, Steacy rarely gets the chance to do much in terms of breaking free of the overly 'talky' nature of TSATP.

Summing up, TSATP is best viewed as an overly ambitious effort to create an sf comic that sought to transcend the (arguably) simplistic approach that marked much of the content present in the genre during the 70s and early 80s.

For a comic series that was first published in 1977, in some respects it was ahead of its time; in other respects, particularly in light of the advent of the sophisticated but entertaining European approaches to sf comics that would come to be showcased in Heavy Metal magazine that very same year, it was an effort that missed the mark.

.jpg)

.jpg)