Book Review: 'Hothouse' by Brian Aldiss

3 / 5 Stars

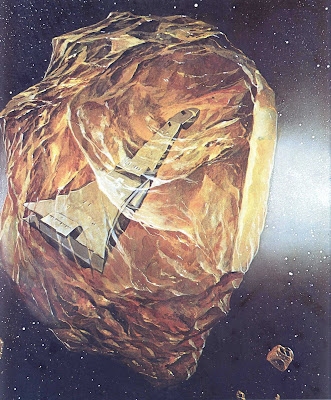

‘Hot House’ was first published as a series of five novelettes in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1961, with the fix-up novel released in the UK in 1962. This Sphere paperback (206 pp) was released in 1971. The cover artwork is by Eddie Jones.

(Abridged versions of ‘Hothouse’, retitled ‘The Long Afternoon of Earth’, were released in the US).

The story is set millions of years into Earth’s future, when the Sun has enlarged (en route to going nova). The planet has stopped rotating, which means that one side is perpetually exposed to the Sun, and has acquired the characteristics of the novel’s title. The other half of the Earth is in perpetual darkness and cold and supports little, if any, life.

On the hothouse side of the Earth, plant life has assumed ecological supremacy; indeed, a single enormous banyan tree occupies most of the terrestrial acreage of the hemisphere. All animal life has long since been extinguished by the increased solar radiation, but mankind lingers on – in the form of 2-feet tall, tarsier-like creatures who survive in the upper branches of the banyan. Life for these people is a constant battle with giant insects and a vicious array of carnivorous plants.

As the novel opens, the reader is introduced to a band of humans, led by the elderly Lily-yo, and featuring the main character, a man-child named Gren. A vividly described series of battles against the relentless plant life results in Gren leaving the tribe, cast into the unknown regions of the forest, filled with creatures even stranger than those occupying the teeming boughs.

As the novel unfolds, Gren finds unlikely allies in his journey across the landscape of this ‘hothouse’. But Gren doesn’t realize that the planet upon which he wanders is itself destined for extinction, for the Sun is beginning to swell even larger…..and soon the plants and animals on the surface of the Earth will have to confront the end of all life..........

For a novel first written in 1962 (and, of course, well before author Aldiss became increasingly infatuated with the New Wave movement and its literary contrivances) ‘Hothouse’ has a surprisingly modern prose style: clean, direct, and for the most part devoid of figurative passages.

The ecology of this far-future Earth is well-conceived, and features some of more interesting monsters depicted in sf. The middle stretches of the narrative do suffer from some loss of momentum, a plain consequence of ‘Hothouse’ s genesis as a fix-up.

But overall, Hothouse stands as one of the better novels the genre produced in the early 60s, and one of its more imaginative treatments of ecology.

Monday, September 30, 2013

Saturday, September 28, 2013

Spaceship size chart

by Dirk Loechel

link from The Verge

Truly a sci-fi fan labor of love, a massive chart comparing the dimensions of an amazing number of ships from books, film, comics, and video and tabletop games.

There are too many entries from 'Warhammer' cluttering up the chart for my taste, but with some careful searching you're sure to find some vessels that you recognize....

Labels:

Spaceship chart by Dirk Loechel

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Born of Ancient Wisdom

'Born of Ancient Wisdom' by Bob Morello (story and art) and Budd Lewis

from Eerie No. 121 (June 1981)

One of the more entertaining stories to appear in Eerie in the early 80s was a three-part serial titled 'Born of Ancient Wisdom', with story and art by Bob Morello (Warren misspelled his surname), and additional story input from Budd Lewis. Episode 1 debuted in Eerie 121, with episodes two and three appearing in Eerie #123 ('In Sight of Heaven, In Reach of Hell', August 1981) and #124 'God of Light', (September 1981).

The series had a unique artistic style, one that probably represented the closest approach of any Warren magazine feature to the Heavy Metal aesthetic that was dominating the comic genre at the time.

I'll be providing the second and third installments of 'Born of Ancient Wisdom' in future posts here at the PorPor Books Blog.

Labels:

Born of Ancient Wisdom

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

Max Headroom by Bryan Talbot

'Max Headroom' by Bryan Talbot

unpublished magazine cover, 1980s

from the book The Art of Bryan Talbot, NBM, 2007

unpublished magazine cover, 1980s

from the book The Art of Bryan Talbot, NBM, 2007

Labels:

Max Headroom by Bryan Talbot

Sunday, September 22, 2013

Book Review: Nowhere on Earth

Book Review: 'Nowhere On Earth' by Michael Elder

2 / 5 Stars

'Nowhere On Earth' was first published in 1972 in the UK by Robert Hale; this mass-market paperback edition was published in the USA by Pinnacle Books in June, 1973. The cover artist is not identified.

The novel is set in the UK in the year 2173. The population stands at 450 million, 5,000 people per square mile, and it's growing. Most of the open land in the British Isles has been paved over to contain high-rise communal apartment, or 'comapt', buildings, which can accommodate the teeming masses only through the use of revolving periods of 8-hour habitation (while one set of lodgers are at work, another set sleeps; when the latter wakes and goes off to work, the other occupants come home for their sleep period).

To keep social unrest from crippling this precarious system, the ruling authorities utilize 'Thought Police', a force comprised entirely of telepaths. The Thought Police constantly hover over the pedways of the city in their air-cars, scanning the minds of the populace, and directing police to apprehend those citizens harboring disruptive thoughts.

When Roger Barclay accompanies his pregnant wife to the hospital, he is filled with anticipation over the forthcoming birth of his daughter. However, Barclay receives crushing news from the doctor attending the birth: due to unforseen complications, both mother and child are dead. Barclay is allowed a brief moment alone with their corpses before they are consigned to the crematorium.

Devastated, Barclay returns to his comapt, there to lie in a stupor. His reverie is interrupted by a vidphone call from none other than his late wife !

Barclay soon finds himself caught up in the sinister machinations of the government and its efforts to control the population. But if he is to have any hope of rescuing his wife, first he will have to discover the truth behind the rumors of a resistance movement, and its charismatic leader, Cornelius Gunn.....

'Nowhere On Earth' is a middling sf novel. Author Elder is a competent writer, and the narrative moves at a good pace.The premise of a dramatically overcrowded England would seem to be a good setting for a sf novel published in the heyday of the Population Crisis.

But I failed to find the novel all that engaging. The plot is more of a backdrop on which the author can tackle the moral and philosophical issues of government surveillance of the thoughts and desires of the inhabitants of his created world, rather than a novel analysis of the way an overpopulated UK might be managed. The book's ending veers into a 'cosmic' solution to things that struck me as contrived.

Unless you're determined to read every sf novel from the early 70s that deals with overpopulation, 'Nowhere On Earth' can be passed by.

2 / 5 Stars

'Nowhere On Earth' was first published in 1972 in the UK by Robert Hale; this mass-market paperback edition was published in the USA by Pinnacle Books in June, 1973. The cover artist is not identified.

The novel is set in the UK in the year 2173. The population stands at 450 million, 5,000 people per square mile, and it's growing. Most of the open land in the British Isles has been paved over to contain high-rise communal apartment, or 'comapt', buildings, which can accommodate the teeming masses only through the use of revolving periods of 8-hour habitation (while one set of lodgers are at work, another set sleeps; when the latter wakes and goes off to work, the other occupants come home for their sleep period).

To keep social unrest from crippling this precarious system, the ruling authorities utilize 'Thought Police', a force comprised entirely of telepaths. The Thought Police constantly hover over the pedways of the city in their air-cars, scanning the minds of the populace, and directing police to apprehend those citizens harboring disruptive thoughts.

When Roger Barclay accompanies his pregnant wife to the hospital, he is filled with anticipation over the forthcoming birth of his daughter. However, Barclay receives crushing news from the doctor attending the birth: due to unforseen complications, both mother and child are dead. Barclay is allowed a brief moment alone with their corpses before they are consigned to the crematorium.

Devastated, Barclay returns to his comapt, there to lie in a stupor. His reverie is interrupted by a vidphone call from none other than his late wife !

Barclay soon finds himself caught up in the sinister machinations of the government and its efforts to control the population. But if he is to have any hope of rescuing his wife, first he will have to discover the truth behind the rumors of a resistance movement, and its charismatic leader, Cornelius Gunn.....

'Nowhere On Earth' is a middling sf novel. Author Elder is a competent writer, and the narrative moves at a good pace.The premise of a dramatically overcrowded England would seem to be a good setting for a sf novel published in the heyday of the Population Crisis.

But I failed to find the novel all that engaging. The plot is more of a backdrop on which the author can tackle the moral and philosophical issues of government surveillance of the thoughts and desires of the inhabitants of his created world, rather than a novel analysis of the way an overpopulated UK might be managed. The book's ending veers into a 'cosmic' solution to things that struck me as contrived.

Unless you're determined to read every sf novel from the early 70s that deals with overpopulation, 'Nowhere On Earth' can be passed by.

Labels:

Nowhere On Earth

Monday, September 16, 2013

Who Do You Think You Are by Bo Donaldson and The Heywoods

'Who Do You Think You Are' by Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods

September 1974

Released in August, 1974, 'Who Do You Think You Are' was Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods' followup single to the their smash hit 'Billy, Don't Be A Hero', which had dominated AM radio airplay all during the Summer of '74.

I remember hearing 'Who Do You Think You Are' in early September '74, and thinking it was a great song. Even today it holds up well as a 70s pop masterpiece.

The song originally was written and performed by the musicians in the British group Jigsaw ('You've Blown It All Sky-High', 1975), who had a UK hit with the song in earlier in 1974.

The Cincinnati-based Donaldson and the Heywoods continue to perform, and their music is available online.

September 1974

Released in August, 1974, 'Who Do You Think You Are' was Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods' followup single to the their smash hit 'Billy, Don't Be A Hero', which had dominated AM radio airplay all during the Summer of '74.

I remember hearing 'Who Do You Think You Are' in early September '74, and thinking it was a great song. Even today it holds up well as a 70s pop masterpiece.

The song originally was written and performed by the musicians in the British group Jigsaw ('You've Blown It All Sky-High', 1975), who had a UK hit with the song in earlier in 1974.

The Cincinnati-based Donaldson and the Heywoods continue to perform, and their music is available online.

Labels:

Who Do You Think You Are

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Book Review: The 1979 Annual World's Best SF

Book Review: 'The 1979 Annual World's Best SF' edited by Donald A. Wollheim

3 / 5 Stars

‘The 1979 Annual World’s Best SF’ (268 pp) was published by DAW Books (DAW Book No. 337) in May, 1979. The cover artwork is by Jack Gaughan.

All of the stories in this anthology first saw print in 1978, mostly in sf digests and magazines.

In his Introduction, editor Wollheim notes that, for sf, 1978 was a ‘terrific and unprecedented’ year, a year which saw the genre experience the greatest commercial success, and popularity, in its history. He notes the central role of film and TV properties like Star Wars, as well as Battlestar Galactica and Superman, in fueling the boom, but also notes that the genre, away from its more commercialized pop culture manifestations, is entering a period of ‘uncertainty’.

I believe that what Wollheim was trying to say was that the New Wave movement – which gets no mention in his Introduction – was, by 1979, losing steam. However, there was nothing to replace it, and the genre would sputter along, offering up the dregs of the New Wave approach, until something came along to revitalize sf. We now know this was, of course, Cyberpunk; but in ’79, 'Neuromancer' was a good five years in the future.

What then, do we get in the 1979 'World’s Best' ?

‘Come to the Party’ by Frank Herbert and F. M. Busby: variation on the theme of Ignorant Terrans Interefere with an Alien Planet’s Ecocystem and Mayhem Ensues. The forced effort at imparting ironic humor to the story, and the use of cutesy terminology – ‘warpling’, ‘Hoojies’, ‘squishes’ – makes this entry seem like a hangover from an issue of Analog magazine (with an Ed Emshwiller cover) ca. 1960.

‘Creator’ by David Lake: labored tale about an omnipotent alien who experiments with a virtual reality simulator (somewhat like a very sophisticated version of Microsoft’s ‘Civilization’ PC game), that recapitulates the rise of life on Earth.

‘Dance Band on the Titanic’ by Jack Chalker: underwhelming allegory about a ferryboat upon which people from parallel universes can co-mingle for the duration of the voyage. The alienated first-person narrator regains his lost belief in the worth and goodness of humanity.

‘Casandra’ by C. J. Cherryh: a woman has disturbing visions of her city in flames. Is she insane, or precongnitive ? A competent, if not particularly original, story.

‘In Alien Flesh’ by Gregory Benford: Reginri the farmhand makes a fateful decision to participate in an unusual experiment involving a whale-like alien species.

‘SQ’ by Ursula K. Le Guin: plodding satire about a scientist who cons the entire planet into adopting a new psychological test of dubious validity. Let's face it: by 1979, LeGuin was running out of ideas, and her work became perfunctory.

‘The Persistence of Vision’ by John Varley: in the late 1990s, in a US wracked by economic and social turmoil, the alienated first-person narrator wanders from one commune to another across the Southwest. Then he comes upon a commune operated by the Kellerites: people who were left blind and deaf by the German Measles outbreak of the mid-60s. The Kellerites communicate via touch, an action they feel is best mediated through orgies (!) The narrator comes to the realization that the Kellerites have founded a new way of living, in which so-called ‘handicaps’ in fact allow for a Transcendence not available to the non-disabled.

‘Persistence’ won both Hugo and Nebula awards for 1979. While it’s competently written, whether it is a classic work of sf is doubtful. I suspect that it was so well received at the time because its humanistic message, however overbearing, provided an optimistic note that countered the pessimism of the late 70s.

‘We Who Stole the Dream’ by James Tiptree, Jr: Diminutive, but brave, aliens conspire to escape their brutal Terran overseers. With some crisp action sequences and a downbeat tenor, this is the best story in the anthology and a fine entrant in the 'Evil Earthmen' sub-genre of science fiction.

‘Scattershot’ by Greg Bear: a young woman must cope with the unusual side-effect of an alien attack on her starship: it is reassembled as a hodge-podge of similar ships, existing in parallel universes. The concept is interesting, but the narrative gets too bogged down in introspective interludes designed to force-feed the reader empathy and insight into the personality of the main character.

‘Carruther’s Last Stand’ by Dan Henderson: variation on the theme of A Crusty Misanthrope Is the Only Person in the World Who can Telepathically Communicate with Distant Aliens. The big revelation that comes at the story’s end is confusingly handled.

Summing up, ‘The 1979 Annual World’s Best SF’ is yet another middling sci-fi anthology. At least the dialed-in entries from ‘name’ authors, that tended to seep the vigor out of many of Wolheim’s ‘World’s Best’ anthologies, are reduced here, giving something of a promising note to the this decade's final entry in the series.

3 / 5 Stars

‘The 1979 Annual World’s Best SF’ (268 pp) was published by DAW Books (DAW Book No. 337) in May, 1979. The cover artwork is by Jack Gaughan.

All of the stories in this anthology first saw print in 1978, mostly in sf digests and magazines.

In his Introduction, editor Wollheim notes that, for sf, 1978 was a ‘terrific and unprecedented’ year, a year which saw the genre experience the greatest commercial success, and popularity, in its history. He notes the central role of film and TV properties like Star Wars, as well as Battlestar Galactica and Superman, in fueling the boom, but also notes that the genre, away from its more commercialized pop culture manifestations, is entering a period of ‘uncertainty’.

I believe that what Wollheim was trying to say was that the New Wave movement – which gets no mention in his Introduction – was, by 1979, losing steam. However, there was nothing to replace it, and the genre would sputter along, offering up the dregs of the New Wave approach, until something came along to revitalize sf. We now know this was, of course, Cyberpunk; but in ’79, 'Neuromancer' was a good five years in the future.

What then, do we get in the 1979 'World’s Best' ?

‘Come to the Party’ by Frank Herbert and F. M. Busby: variation on the theme of Ignorant Terrans Interefere with an Alien Planet’s Ecocystem and Mayhem Ensues. The forced effort at imparting ironic humor to the story, and the use of cutesy terminology – ‘warpling’, ‘Hoojies’, ‘squishes’ – makes this entry seem like a hangover from an issue of Analog magazine (with an Ed Emshwiller cover) ca. 1960.

‘Creator’ by David Lake: labored tale about an omnipotent alien who experiments with a virtual reality simulator (somewhat like a very sophisticated version of Microsoft’s ‘Civilization’ PC game), that recapitulates the rise of life on Earth.

‘Dance Band on the Titanic’ by Jack Chalker: underwhelming allegory about a ferryboat upon which people from parallel universes can co-mingle for the duration of the voyage. The alienated first-person narrator regains his lost belief in the worth and goodness of humanity.

‘Casandra’ by C. J. Cherryh: a woman has disturbing visions of her city in flames. Is she insane, or precongnitive ? A competent, if not particularly original, story.

‘In Alien Flesh’ by Gregory Benford: Reginri the farmhand makes a fateful decision to participate in an unusual experiment involving a whale-like alien species.

‘SQ’ by Ursula K. Le Guin: plodding satire about a scientist who cons the entire planet into adopting a new psychological test of dubious validity. Let's face it: by 1979, LeGuin was running out of ideas, and her work became perfunctory.

‘The Persistence of Vision’ by John Varley: in the late 1990s, in a US wracked by economic and social turmoil, the alienated first-person narrator wanders from one commune to another across the Southwest. Then he comes upon a commune operated by the Kellerites: people who were left blind and deaf by the German Measles outbreak of the mid-60s. The Kellerites communicate via touch, an action they feel is best mediated through orgies (!) The narrator comes to the realization that the Kellerites have founded a new way of living, in which so-called ‘handicaps’ in fact allow for a Transcendence not available to the non-disabled.

‘Persistence’ won both Hugo and Nebula awards for 1979. While it’s competently written, whether it is a classic work of sf is doubtful. I suspect that it was so well received at the time because its humanistic message, however overbearing, provided an optimistic note that countered the pessimism of the late 70s.

‘We Who Stole the Dream’ by James Tiptree, Jr: Diminutive, but brave, aliens conspire to escape their brutal Terran overseers. With some crisp action sequences and a downbeat tenor, this is the best story in the anthology and a fine entrant in the 'Evil Earthmen' sub-genre of science fiction.

‘Scattershot’ by Greg Bear: a young woman must cope with the unusual side-effect of an alien attack on her starship: it is reassembled as a hodge-podge of similar ships, existing in parallel universes. The concept is interesting, but the narrative gets too bogged down in introspective interludes designed to force-feed the reader empathy and insight into the personality of the main character.

‘Carruther’s Last Stand’ by Dan Henderson: variation on the theme of A Crusty Misanthrope Is the Only Person in the World Who can Telepathically Communicate with Distant Aliens. The big revelation that comes at the story’s end is confusingly handled.

Summing up, ‘The 1979 Annual World’s Best SF’ is yet another middling sci-fi anthology. At least the dialed-in entries from ‘name’ authors, that tended to seep the vigor out of many of Wolheim’s ‘World’s Best’ anthologies, are reduced here, giving something of a promising note to the this decade's final entry in the series.

Labels:

The 1979 Annual World's Best SF

Thursday, September 12, 2013

A Time of Changes by Bruce Pennington

'A Time of Changes'

by Bruce Pennington

cover artwork for the novel by Robert Silverberg

Panther (UK) 1974

from the book Ultraterranium: The Paintings of Bruce Pennington

by Bruce Pennington

cover artwork for the novel by Robert Silverberg

Panther (UK) 1974

from the book Ultraterranium: The Paintings of Bruce Pennington

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko

Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko

Dark Horse / New Comic Company

2013

'Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko' (New Comic Company / Dark Horse Books, August 2013) is the latest in the Eerie Presents / Creepy Presents series.

(Previous volumes are Creepy Presents: Bernie Wrightson, Eerie Presents: Hunter, Creepy Presents: Richard Corben, and Eerie Presents: El Cid).

Like others in the series, the book is a quality, hardbound collection of comics originally appearing in Creepy and / or Eerie in the 60s, 70s, and early 80s, and an affordable alternative to the $50 volumes of the New Comic Company 'archive' collections for these Warren magazines.

Late in 1965, or perhaps early in 1966 (the exact date is unsure) Steve Ditko (b. 1927) quit working for Marvel, after increasing disagreements with Stan Lee rendered communication between the two men impossible. Ditko began working for other publishers, including Charlton and DC, and did not resume working for Marvel until 1979.

In 1966, Ditko began to work with editor Achie Goodwin at Warren, and over a two-year span he produced 16 strips for Creepy and Eerie. This volume reprints those 16 strips.

As always, New Comic Company's Mark Evanier does a good job with the Introduction, and the reproductions of the comics are of good quality. Ditko's work for Warren included classic horror stories, as well as some fantasy and sword-and-sorcery strips.

Ditko took a varied approach to his illustrative style. Sometimes he relied on pen-and-ink line work, as in 'Collector's Edition' (where he also worked in Zip-A-Tone effects on the bottom-most panels):

But most of his work relied on an ink-wash technique:

With the exception of 'The Sands That Change', a really cruddy effort, the comics that Ditko did for Warren display his skills to good effect.

However, I suspect that most purchasers of 'Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko' will be people over 30 years of age, including Baby Boomers who fondly remember the Warren magazines from their youth.

Ditko's artwork is probably too idiosyncratic to draw much attention from younger comics fans, who have been reared on comics composed and colored using PC software. It's increasingly difficult nowadays to find a comic book from any major publisher in which the stippling, shading, or cross-hatching that defined Ditko's approach, is a major part of any draftsmanship.

With the exception of dedicated black-and-white publications, like the so-so reboot of 'Creepy Comics' that Dark Horse has launched, most contemporary readers are going to be familiar with comics that have adopted the aesthetic of line drawings, flat colors, and 'manga' or 'indie' stylings. To them, the visual flavor of the Ditko strips from the 60s may seem strange and unappealing.

Dark Horse / New Comic Company

2013

'Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko' (New Comic Company / Dark Horse Books, August 2013) is the latest in the Eerie Presents / Creepy Presents series.

(Previous volumes are Creepy Presents: Bernie Wrightson, Eerie Presents: Hunter, Creepy Presents: Richard Corben, and Eerie Presents: El Cid).

Like others in the series, the book is a quality, hardbound collection of comics originally appearing in Creepy and / or Eerie in the 60s, 70s, and early 80s, and an affordable alternative to the $50 volumes of the New Comic Company 'archive' collections for these Warren magazines.

Late in 1965, or perhaps early in 1966 (the exact date is unsure) Steve Ditko (b. 1927) quit working for Marvel, after increasing disagreements with Stan Lee rendered communication between the two men impossible. Ditko began working for other publishers, including Charlton and DC, and did not resume working for Marvel until 1979.

In 1966, Ditko began to work with editor Achie Goodwin at Warren, and over a two-year span he produced 16 strips for Creepy and Eerie. This volume reprints those 16 strips.

As always, New Comic Company's Mark Evanier does a good job with the Introduction, and the reproductions of the comics are of good quality. Ditko's work for Warren included classic horror stories, as well as some fantasy and sword-and-sorcery strips.

Ditko took a varied approach to his illustrative style. Sometimes he relied on pen-and-ink line work, as in 'Collector's Edition' (where he also worked in Zip-A-Tone effects on the bottom-most panels):

But most of his work relied on an ink-wash technique:

With the exception of 'The Sands That Change', a really cruddy effort, the comics that Ditko did for Warren display his skills to good effect.

However, I suspect that most purchasers of 'Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko' will be people over 30 years of age, including Baby Boomers who fondly remember the Warren magazines from their youth.

Ditko's artwork is probably too idiosyncratic to draw much attention from younger comics fans, who have been reared on comics composed and colored using PC software. It's increasingly difficult nowadays to find a comic book from any major publisher in which the stippling, shading, or cross-hatching that defined Ditko's approach, is a major part of any draftsmanship.

With the exception of dedicated black-and-white publications, like the so-so reboot of 'Creepy Comics' that Dark Horse has launched, most contemporary readers are going to be familiar with comics that have adopted the aesthetic of line drawings, flat colors, and 'manga' or 'indie' stylings. To them, the visual flavor of the Ditko strips from the 60s may seem strange and unappealing.

If you're a fan of Ditko's unique artwork, then 'Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko' certainly is worth picking up.

Labels:

Creepy Presents: Steve Ditko

Friday, September 6, 2013

Contact by Tim Conrad

'Contact' by Tim Conrad

from the October, 1981 issue of Epic Illustrated

Timothy Leary gets Cosmic....with the help of some great artwork by Tim Conrad.

from the October, 1981 issue of Epic Illustrated

Timothy Leary gets Cosmic....with the help of some great artwork by Tim Conrad.

Labels:

Contact by Tim Conrad

Tuesday, September 3, 2013

Book Review: Cheon of Weltanland

Book Review: 'Cheon of Weltanland' by Charlotte Stone

Gor Fanboy score: 4 / 5 Stars

‘Cheon of Weltanland’ (205 pp) was published by DAW Books in November, 1983. It is DAW Book No. 552, and features a quintessential ‘barbarian wench’ cover illustration by Boris Valejo: our heroine, wearing – naturally enough- a metal bikini, totes the severed head of an enemy, while behind her, a a big-bootyed black girl, sporting an afro-puff, clings to a pillar, overcome with shock and awe.

Gor Fanboy score: 4 / 5 Stars

‘Cheon of Weltanland’ (205 pp) was published by DAW Books in November, 1983. It is DAW Book No. 552, and features a quintessential ‘barbarian wench’ cover illustration by Boris Valejo: our heroine, wearing – naturally enough- a metal bikini, totes the severed head of an enemy, while behind her, a a big-bootyed black girl, sporting an afro-puff, clings to a pillar, overcome with shock and awe.

According to the Science Fiction Encyclopedia, 'Charlotte Stone' is the pseudonym of Charles Nightingale and Dominique Roche. 'Cheon' apparently is their first and only published novel.

By the late 70s, the commercial success of the Gor books had cued sf and fantasy publishers to the fact that there was a huge readership available for tales of warrior woman in chain-mail bikinis who regularly underwent abuse and humiliation at the hands of mightily-thewed barbarians.

Janet Morris’s 1977 Bantam book ‘The High Couch of Silistra’ was the first series to capitalize on the 'barbarian wench' trend, followed by Sharon Green’s ‘Mida’ series for DAW.

So it was only natural for DAW to want to expand the genre, and thus, ‘Cheon’ appeared as volume one ('The Four Wishes') of a proposed series. For whatever reason, however, the remaining volumes never appeared, leaving Cheon stuck in the fantasy fiction publishing version of limbo.

‘Cheon’ is designed to cater to the Gor fanboy:

Our heroine has the looks of a swimsuit model, the body of an Olympic pole vaulter, and…..she’s SUPER BUTCH !

That last characteristic gives author Stone the excuse to regularly spice up her narrative with softcore porn scenes, in which Cheon seduces yet another nubile, innocent, teenage girl - !

Throw in assorted bloody battles against raiders and monsters, a first-person narrative that studiously adopts the stilted style of the Gor books, and you’ve got the ideal package to capture, and hold, the fanboys.

[In fairness, author Stone provides a passage in which Cheon openly mocks the premise of the Gor novels, thus making clear that, in this series at least, no barbarian warrior would come ‘round to persuade Cheon to wear slave bracelets and succumb to the dominance of a man.]

In summary, I give ‘Cheon of Weltanland’, despite its orphan status, a Gor Fanboy Score of 4 Stars.

By the late 70s, the commercial success of the Gor books had cued sf and fantasy publishers to the fact that there was a huge readership available for tales of warrior woman in chain-mail bikinis who regularly underwent abuse and humiliation at the hands of mightily-thewed barbarians.

Janet Morris’s 1977 Bantam book ‘The High Couch of Silistra’ was the first series to capitalize on the 'barbarian wench' trend, followed by Sharon Green’s ‘Mida’ series for DAW.

So it was only natural for DAW to want to expand the genre, and thus, ‘Cheon’ appeared as volume one ('The Four Wishes') of a proposed series. For whatever reason, however, the remaining volumes never appeared, leaving Cheon stuck in the fantasy fiction publishing version of limbo.

‘Cheon’ is designed to cater to the Gor fanboy:

Our heroine has the looks of a swimsuit model, the body of an Olympic pole vaulter, and…..she’s SUPER BUTCH !

That last characteristic gives author Stone the excuse to regularly spice up her narrative with softcore porn scenes, in which Cheon seduces yet another nubile, innocent, teenage girl - !

Throw in assorted bloody battles against raiders and monsters, a first-person narrative that studiously adopts the stilted style of the Gor books, and you’ve got the ideal package to capture, and hold, the fanboys.

[In fairness, author Stone provides a passage in which Cheon openly mocks the premise of the Gor novels, thus making clear that, in this series at least, no barbarian warrior would come ‘round to persuade Cheon to wear slave bracelets and succumb to the dominance of a man.]

In summary, I give ‘Cheon of Weltanland’, despite its orphan status, a Gor Fanboy Score of 4 Stars.

Labels:

Cheon of Weltanland

Sunday, September 1, 2013

Mechanismo by Harry Harrison

'Mechanismo' by Harry Harrison

In the late 70s Harry Harrison authored several trade

paperback, sf art books : 'Great Balls of Fire' (1977), 'Mechanismo' (1978) and

'Planet Story' (1979). This was something of an adventure in sf publishing, for

at that time, art books with sf or fantasy themes were comparatively rare, and

the chain stores (Waldenbooks, Coles, and B. Dalton) that dominated the retail

sphere in those days were only just beginning to realize that additional shelf

space and inventory should be devoted to the genre.

Mechanismo (120 pp) is printed on quality stock, and at 10 ¼

x 10 ¼ “, couldn’t entirely fit onto the platen of my scanner. So the images I’m

posting here are cropped to some extent.

Angus McKie

Harrison’s contribution are 6 short essays on ‘Star Ships’, ‘Mechanical

Man’, Weapons and Space Gear’, ‘Space Cities’, ‘Fantastic Machines’, and ‘Movies’.

Additional text, apparently supplied by the publisher, provides commentary –

some of it fictional – for the illustrations. Most (all ?) of the artwork in

Mechanismo was previously published, usually as cover art for sf paperbacks

published in the UK.

Colin Hay

Jennifer Eachus

Richard Clifton-Dey

Overall,

Harrison’s essays are entertaining rather than pedantic, and written with a

note of humor. There are some tidbits dropped that may move readers to seek out

70s sf novels and story collections (for example, I’d never been aware of

Harrison’s matter transmission anthology, 'One Step from Earth' (1970), prior to

reading about it in Mechanismo).

Robin Hiddon

Jim Burns

Angus McKie

The quality of pieces (which are reproduced in black and

white and color) from the 19 participating artists varies; some are well done,

while others are mediocre. The works by Jim Burns, a rising star in the sf

illustration field, are among the most eye-catching. There are a large number

of contributions from Angus McKie, the leading sf illustrator in the late 70s

and a frequent contributor to Heavy Metal magazine. Ralph McQuarrie provides

some paintings from Star Wars, and there are a couple of H. R. Giger

submissions, too.

Angus McKie (cover of the March, 1979 issue of Heavy Metal)

‘Mechanismo’ may not draw much enthusiasm from contemporary

sf fans, who are used to the revolutionary changes in sf and fantasy

illustration wrought by the use of computers and illustration software. But

those with a nostalgic bent may want to pick up Mechanismo and take in the

flavor of Old School sf illustration.

Angus McKie

Ralph McQuarrie

Labels:

Mechanismo

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)